The year ahead at Westminster

- Published

After the election, the numbers in both Houses of Parliament looked pretty daunting for the government whips.

In the Commons, the Conservative majority of 12 looked paper-thin, and susceptible to all manner of rebellions from a variety of different quarters: in the Lords, the Conservatives, for the first time in their history, faced the prospect of governing without a majority of peers behind them.

But as 2016 dawns, those whips may be breathing just a little easier.

EU sniping

By normal standards, the government should be having rather a hard time at the moment, with its somersault with triple salko over tax credit cuts, its latest postponement of a decision on Heathrow expansion (supposedly a vital infrastructure issue), not to mention the increasingly nasty internal sniping over David Cameron's EU membership renegotiation.

But sitting on a double-digit opinion poll lead, ministers can, instead, contemplate Labour's disarray, the Lib Dems' near disappearance and the SNP's enthusiasm for sniping at Labour, as well as them.

When ministers come to propose the renewal of Trident, for example, they can expect a number of Labour MPs to support them, or at least abstain. And if Jeremy Corbyn seeks to overrule his MPs on this issue, by polling Labour Party members, the internal bitterness in the Parliamentary Labour Party will doubtless deepen, and a couple of shadow cabinet members could well depart.

It's an example of how a controversial decision will be masked by a Labour split.

The most troublesome issues for government should be those where most opposition parties are united against them and where 10 or more Conservative MPs are prepared to break ranks.

Take the Investigatory Powers Bill, where Tory civil libertarians like David Davis are deeply unhappy about the internet data powers the government wants to take. Mr Davis is a seasoned parliamentary guerrilla, capable of causing real trouble with a combination of tactical streetsmarts and a proven ability to work with opposition MPs - he has an excellent working relationship with one Tom Watson, now deputy leader of the Labour Party.

Labour disagreements

They might be able to engineer a Commons defeat for the government on some aspect of the Bill, perhaps to require judicial warrants for intercepts, but this is only possible if Labour can present a united front.

Shadow home secretary Andy Burnham at first seemed to welcome the draft Bill, which is being scrutinised by a special parliamentary committee, and then raised questions afterwards - a performance that smacked of internal disagreement.

And that in turn raises questions about whether Labour has the flexibility to support the Bill in general while attempting to defeat the government on a key part of it. We shall see.

And what about their lordships' House? The government is attempting to re-write the rules on secondary legislation, after its stinging defeat on tax credits in October.

But that defeat masked an interesting fact - that the government is starting to win a few more contentious votes in the Lords. Shortly after that tax credit vote, it defeated a move to postpone a switch to individual voter registration, largely because a few Labour peers failed to turn out.

More recently the government whips have seen off the Opposition on votes for 16 and 17-year-olds in the EU referendum.

The tax credits battle pitted the Commons against the Lords

Not long ago, they might have lost both those votes, and I suspect there are three factors behind the change.

First, the steady trickle of new Tory peers has tipped the balance just a little away from the Opposition. Second, I think some Labour peers' disenchantment with their new leadership is beginning to manifest itself and third, I think some Labour peers are increasingly reluctant, on constitutional grounds, to push their luck in defying the will of the Commons.

Doubtless their lordships will remain a bit of a thorn in ministerial sides, but the House now seems slightly less willing to tweak the government's nose, and slightly less willing to persist in its resistance, if the Commons refuses to accept changes it has made.

Ministers can still expect a rough ride on the Welfare Reform, Immigration, Trade Union Reform and Housing Bills and may have to offer concessions to smooth the way.

But I suspect that after the tax credits kerfuffle, ministers will be less keen to try and implement major policy changes via statutory instruments, whether or not peers' powers to reject them are reformed, so SIs, at least, will sink back into their normal obscurity.

All these factors will play out as Parliament digests the remaining bills for this session - the Wales Bill, the promised Buses Bill, Extremism Bill, Policing and Criminal Justice Bill and Votes for Life Bill.

I expect particular fun with the Scotland Bill - where the wily ex-Scottish Secretary, Lord Forsyth, is leading strong guerrilla resistance in the Lords, which may even mean that the promised new devolution of powers is not delivered before the elections to the Scottish parliament in May.

A key issue here is the "fiscal framework" for the new deal, which is fundamental but which has not yet been settled.

EU debate

So there's plenty of meaty legislation due in Parliament in 2016, but the year's greatest political debate won't be in Parliament at all, although much of what happens within Westminster will be driven by it.

The long-promised in-out EU referendum may well happen well before the 2017 deadline set by the recently passed EU Referendum Act - perhaps as early as June or July 2016.

At the formal parliamentary level, many of the select committees will attempt to inform the referendum debate by reporting on the implications of the decision for their particular areas - and it will be interesting to see if any of them come off the fence and offer more than a neutral "on the one hand-on the other hand" assessment.

But what Westminster's really watching for is the first Cabinet minister to break ranks.

Unless David Cameron defies expectations and heads the campaign to leave the EU, the prime minister will have to decide whether he can insist that all his ministers back whatever deal he achieves to reform Britain's membership terms - so any minister who does not will have to resign.

Quite a number of Cabinet ministers have long Eurosceptic pedigrees and they will come under intense scrutiny when the shape of the deal is finally clear.

David Cameron has promised an EU referendum by the end of 2017

For me, though, the key figure is Theresa May, the Home Secretary. At this stage it is, of course, impossible to predict how she will respond to an as-yet un-negotiated agreement.

But were she, as the minister in charge of Britain's borders since 2010, to announce that immigration could not be controlled from within the EU, that would deliver a hammer-blow to the prime minister and to the campaign to remain.

Another factor which would surely figure in the calculations of potential rebels is that the first Cabinet minister to join the leave side would also pole-vault into contention for the party leadership, rather as John Redwood did when John Major resigned his party leadership in an attempt to assert his authority over euro-rebels in 1995.

So expect plenty of attempts to draw out Cabinet ministers' views on the EU, from both Conservative factions and from the Opposition, on every possible parliamentary occasion - question times, statements, debates, whatever. Enquiring minds want to know.

While the Tories focus on the referendum, the May round of local elections, and Scottish and Welsh elections, look critical to all the leaders of opposition parties.

Jeremy Corbyn will wish to show his reshaping of Labour has appeal for the voters - his internal opposition will seize on any reverse to show that it is frightening them away.

Jeremy Corbyn's Labour leadership will be tested in local elections in May

But the results also matter for Tim Farron, who needs some compelling evidence that the Lib Dems are still alive, and for Nigel Farage, who, after crushing disappointment last May, and in the Oldham by-election, needs to show that UKIP is still a force to be reckoned with. Both parties could be destabilised by defeat.

In Scotland the SNP expects to maintain its supremacy - but Labour desperately needs some evidence of a comeback. Jeremy Corbyn can hardly be blamed if such evidence does not materialise, because Scottish Labour's collapse was at least a decade in the making, but Labour needs Scottish seats if it is to be a credible challenger for Government in 2020, and a lack of progress will feed into its internal battles.

So MPs across all the parties will have plenty to preoccupy them, before we get to the business of actual law-making - and one big career issue will be the question of whether they still have a seat.

The government is committed to reduce the number of MPs from 650 to 600, and to ending the sharp variations in the number of voters in different seats. That change will affect almost all MPs - so while largely invisible, it will be a driver for much that goes on.

Boundary changes

Labour MPs feeling vulnerable after the change in leadership, and more particularly, the influx of new party members, will be painfully aware that they will almost all have to go through a reselection process for the redrawn constituencies, and a number fear they will not survive.

Welsh Tories could see their hard-won gains since their wipe-out in 1997 eroded by unfavourable new seat boundaries, and the surviving Lib Dem MPs could see their local campaigning edge removed, if large numbers of new voters are tacked onto their few remaining strongholds. And in Northern Ireland a cut in the overall number of MPs could be bad news for all the parties there.

And there's another point about the boundary review - it will be based on new electoral registers compiled under IVR - individual voter registration - a system based on each adult registering themselves to vote, rather than depending on a head of household.

Labour fears it will drive many of their voters off the register - and one unremarked feature of the Oldham by-election was that it was fought on the first electoral register to be compiled under IVR.

The word is that more voters, even than Labour campaigners feared, vanished from the register. You can argue about whether they existed in the first place or whether they were pushed off by the change in the system, but this matters because it makes it more likely that the new constituency boundaries will be very bad news for Labour.

Small, safe inner city seats which are found to have too few voters, for example, could suddenly become marginal with the addition of a chunk of Conservative-voting suburbia. But the opposition disarray may mean they can't derail the process, however much they want to.

City devolution

Away from London the ramifications of the new big-city politics being fostered by the Communities Secretary, Greg Clark, will become more obvious for Parliament, as more of the new breed of elected "Metro Mayors" set up shop.

Greater Manchester is the first area to agree to a new "metro mayor"

One of the first manifestations may be that quite a number of MPs quit the Commons, if they are elected to run these powerful new authorities (remember, a number left to become police and crime commissioners in the last Parliament).

Greater Manchester is the first - but new authorities covering most of the major conurbations, and sometimes taking in rural areas between them, will follow. Some MPs are a bit queasy about the implications. On one level they will be faced with major new local figures, who may turn out to be bigger beasts than they are. But, secondly, they may find that these powerful new players can make changes to local services in their constituencies which then rebound on them.

Committee power

The first months of the 2015 Parliament have proved a happy hunting ground for the Commons' select committees - with David Cameron forced to issue a personal response to the foreign affairs committee's report recommending no armed intervention in Syria, in order to bolster support for British airstrikes.

Then there's the health committee's push for an anti-obesity sugar tax, which is unlikely to end with the publication of their report.

Under its new chair, Neil Carmichael, the education committee has demonstrated an appetite for cross-departmental work with other committees on productivity (with the BIS Committee) and early years (with the DWP Committee) and they too could have the weight to start influencing government policy.

The amount of clout a committee has depends, crucially, on the effectiveness of whoever's in the chair - and most of the current crop look extremely ambitious.

Rebuilding Westminster

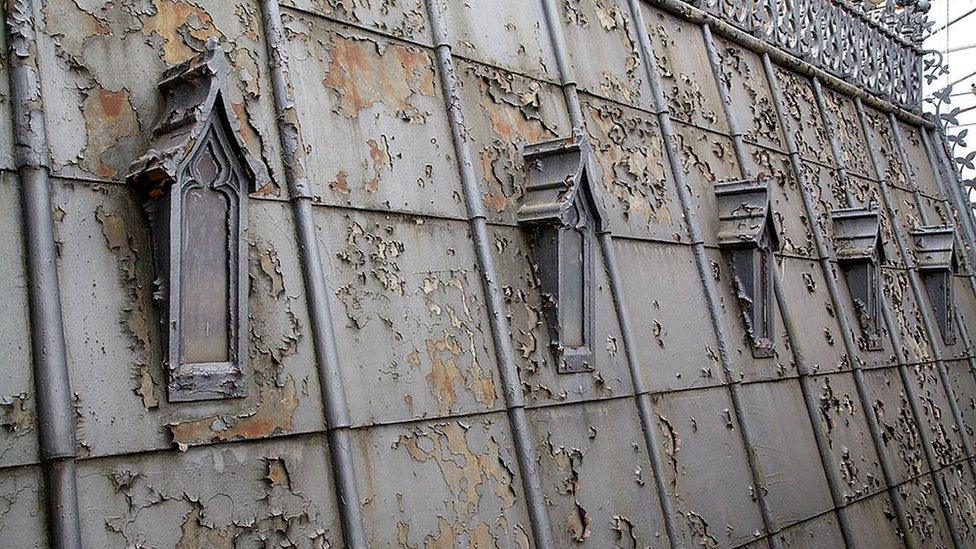

There are Westminster domestic issues too. Halfway through the year, the special committee of MPs and peers on the restoration of the Palace of Westminster will report on the options for the multi-billion pound revamp the building needs - with particular interest in whether some, or all of the parliamentarians will have to move out while the work is done - although this is most unlikely to happen before 2020 at the earliest.

The crumbling Palace of Westminster is said to need billions of pounds of repairs

The parliamentarians are extremely nervous that, if they move completely out of Westminster, they will never get back in, and that, somehow, their iconic home will be sold off as a hotel, or something similar.

The other interesting aspect of the scheme is the extent to which the powers that be will seek to re-imagine the Parliamentary buildings, and maybe come up with a scheme which balances the needs of a 21st century legislature with the requirements of the vastly increased numbers of visitors, and of the need for much tighter security.

But change will be a long time coming. We may be a year into the 2020 Parliament before one or both Houses have to move out, to make way for the builders - and it could be several years after that before the reshaped Palace of Westminster emerges, phoenix-like, from the old.