What the two party leaders have in common

- Published

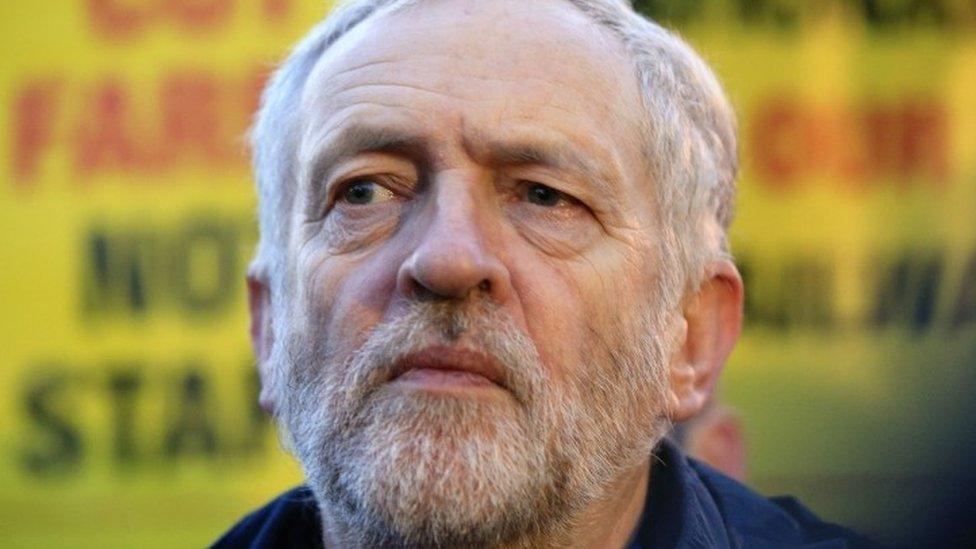

What have David Cameron and Jeremy Corbyn got in common? At first glance, really, seriously, not very much. But maybe the two men do share something.

Whether David Cameron's climbdown on allowing his cabinet ministers to campaign to leave the European Union, or Jeremy Corbyn's (ongoing) chaotic reshuffle, both have been forced to realise they might officially be in charge of their parties, but they still can't get everything they want.

But while the Labour reshuffle grinds on, the prime minister's admission that he's had to shift, is unquestionably the more significant political decision of the day.

By the close of last year it was probably inevitable. It's also inevitable that in some quarters it's been described as crazy, in others as canny, and there will never be agreement on which it is. But what does it tell us about what could be a dramatic six months ahead?

1. Most importantly, announcing the decision today is a big sign of David Cameron's confidence that he'll get a deal he can sell to the public in February with a vote perhaps as early as June.

2. Much of the running here, and perhaps all along, has been made by Eurosceptics in the Conservative Party. In the words of one minister "they are framing it all", and David Cameron's reversal of his position from 12 months ago when he ruled out a free vote has been forced by pressure from those who want to leave the EU.

3. Government ministers may end up publicly arguing against each other on TV and radio, in the pages of the papers and in public debates. Politicians abroad, and some members of the public, may think it is pretty weird. Supporters of the move say it is "mature". It may all seem rather strange.

4. Despite warnings from figures like Lord Heseltine that it will make David Cameron look a "laughing stock", in the view of most Conservatives it is plainly better than the alternative - ministers spitting tacks privately for several months, and then noisy resignations in the run up to a critical vote. One minister told me the PM has "used his choice wisely".

5. The danger for the Conservatives is that senior figures will rather enjoy the liberty of being able to speak freely and recreating party discipline after the referendum, whatever the result, will seem impossible.

6. There are uncanny parallels with the last time we were all asked to vote on staying in or out, in 1975. It was a Labour prime minister then, Harold Wilson, who was forced to allow his cabinet ministers to argue for different positions because so many of them wanted to leave. After Wilson failed to secure major changes to what was then the EEC, he had to offer an "agreement to differ" to his cabinet, as he had no hope of stitching together the splits in his party, divisions that took years to heal. That's a parallel David Cameron will hope to escape.

- Published14 September 2015

- Published4 January 2016

- Published5 January 2016