The real story behind the Labour reshuffle

- Published

Labour advisers from rival camps hovered around each other, awkwardly, in the coffee queue.

One of the frontbenchers who quit rushed along, head down. The only thing some Labour MPs, apparatchiks and shadow ministers going about their business in Parliament today have got in common is the grey bags under their eyes due to a lack of sleep.

In the last four days there have been sackings, resignations, threats of resignations, private frustrations and arguments, and discussions, endless discussions.

Bad blood

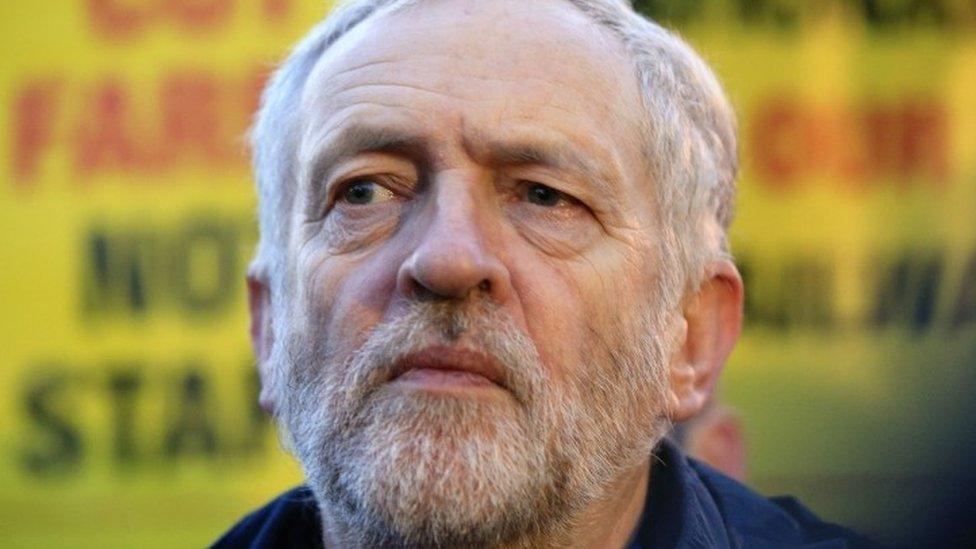

Jeremy Corbyn now, finally, has his new team. And it's not even very different to the old one.

It's not clear that the levels of drama really merit four departures, two different names in the shadow cabinet, and a handful of new faces in the shadow frontbench team. There were always going to be disagreements inside Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party that were more intense than in most political parties, which are realistically, always awkward coalitions.

But this week, bad blood has turned into poison. How did it all go so badly wrong?

Mr Corbyn's supporters deny they were behind the frenzy of prediction that preoccupied the press and much of the Labour Party over the Christmas break about the plans Jeremy Corbyn had for a "revenge reshuffle".

But at the end of last weekend it was clear the leader did want to change his shadow foreign secretary and shadow defence secretary, Hilary Benn and Maria Eagle.

Mr Benn had to be moved after his speech supporting air strikes on Syria, one Corbyn supporter told me - because "there's a time and a place for that kind of theatrics. If his intentions were not to embarrass Corbyn, then what was he doing?"

'Notes taken'

He and Eagle had to be shifted, some believed, and Corbyn intended to "push his chips to the max".

Some of his supporters also wanted to shift the chief whip, Rosie Winterton and her team, Alan Campbell and Mark Tami. They're not exactly well-known names, but critical to the day-to-day functioning of the Labour Party.

At this stage, I'm also told notes had been taken of the "disloyalties" of Pat McFadden, the now departed shadow Europe minister. The pointed comments of Michael Dugher, the former shadow culture secretary, had also not gone unnoticed by Corbyn's backers.

New faces and old (clockwise from top left): Hilary Benn, Maria Eagle, Emily Thornberry, Michael Dugher, Pat Glass and Pat McFadden

Having gathered together in Parliament on Monday morning before most MPs returned to Westminster the next day, after lunch the reshuffle was ready to begin.

The intention was not for a huge clearout but for a handful of specific changes that would send a clear message to the rest of the party and give Jeremy Corbyn more control over his party on the issues closest to his heart - international relations and defence.

The plans immediately hit an obstacle. Senior sources suggest the first meeting with the chief whip, Rosie Winterton, on Monday afternoon spelled out the level of resistance to the planned changes.

'Carnage' warning

I'm told she made clear she would resign if the leader fired her team, and that if Hilary Benn were fired, a significant number of the shadow cabinet would walk in protest.

One senior figure told me on Monday night: "The shadow cabinet is almost unified in opposing moving Benn. There will have to be a climbdown or there will be carnage."

Those who might have considered their positions include Andy Burnham, Lucy Powell, Angela and Maria Eagle, and Vernon Coaker. One source claimed as many as 15 junior ministers would go too.

Through the afternoon, several shadow cabinet ministers were asked to come into Parliament or to expect phone calls. But crucially, I'm told even after weeks of speculation over the changes, it was only on Monday afternoon that the viability of the planned changes were discussed outside Mr Corbyn's supporters.

One senior figure described it as "the first time Jeremy Corbyn has started to work out there are consequences".

No surprise perhaps that hours and hours of difficult conversations, including a meeting of more than an hour between Mr Corbyn and Mr Benn, reached no conclusion.

Twitter announcement

It had been made plain to him the most significant of the changes he wanted to make would face a huge backlash, and he didn't appear to want to go fully ahead. Just before 10pm his spokesman told me there had been long discussions and soundings, with "announcements to come in due course".

At midnight on Monday however, sources in the rest of the shadow cabinet were sure of the shape of the changes - Mr Corbyn would not sack Hilary Benn, he wanted to sack Michael Dugher, and move Maria Eagle to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, with Emily Thornberry a possible - if controversial - replacement for her at defence.

Mid-morning on Tuesday, the first actual sacking was revealed. Not by the leader's office, but by Michael Dugher himself, tweeting, external that he had been sacked.

Rather than silently await their fate, or actual announcements from Team Corbyn, nine members of the shadow cabinet praised him, lamenting his loss on social media.

As the hours ticked by towards David Cameron's statement on Europe in the Commons - when he was to announce a significant climbdown on the EU - it still seemed the announcement of the expected changes would happen at any moment.

Surely, the leader's office wouldn't allow the front bench to take their seats without knowing if they'd still be allowed to sit there for very much longer? But that is exactly what happened.

After midnight

On the way to the statement one shadow cabinet minister joked to me: "Whoever gets to the front bench in time keeps their job."

The Labour front bench sat together, but tense and stony throughout.

It still seemed like the most likely outcome would be a move for Maria Eagle, Mr Benn staying put, and probably Emily Thornberry into defence. But as the hours ticked by and there was no signal from the leader's office, rumours ran wild.

Reporters loitered outside Jeremy Corbyn's Westminster office

One shadow cabinet member said to me, "It seemed like it was on, then it was off."

In the end, it was not until Parliament's cleaning staff had had to vacuum around those gathered reporters, after midnight, that the first announcement came - the sacking of Pat McFadden as shadow Europe minister.

The bitter backlash of the moves followed on Wednesday morning. Three junior shadow ministers departing in protest, on TV, on radio and Facebook.

Lasting impact

Spats broke out in public and in private over the deal that had really been agreed with Hilary Benn.

Claims that he'd agreed to swallow his criticisms of Mr Corbyn, although he insisted that nothing had changed. Accusations made by both sides that they were misrepresenting the facts. Not then until Thursday morning that the last of the names emerged with the final shape of Mr Corbyn's new team. And without a polygraph, it is impossible to tell exactly what really happened.

But what is clear is that the last few days will have a lasting impact on the Labour Party. There were only minor moves in number, but the consequences could be major.

Shadow defence minister Kevan Jones was among those to quit

Reshuffles are a test of any political leader's authority. And while it sounds a contradiction, Jeremy Corbyn's performance has been, at once, both feeble and strong.

Strong in that he achieved his aim of a new face at defence, partly neutralising a future row over the nuclear deterrent by putting a fellow opponent of Trident in charge.

Forceful in sacking two effective Westminster operators, Michael Dugher and Pat McFadden, who disagreed with him and were willing to say so. He increased the number of women in the shadow cabinet too, and now has a team that reflects better his positions.

Divisions

Yet the Labour leader found he did not have the clout to drive through all the changes he wanted. The political pantomime has exposed again his team's lack of experience in just getting things done.

And that handling, the days of concern and chaos, have deepened the hostility between Mr Corbyn and some Labour MPs - accelerating perhaps the move towards a narrower political platform from where, recent history suggests, elections are harder to win.

And sacking Michael Dugher and Pat McFadden has put two of Labour's canniest political operators on the backbenches with more time to spare.

Given the hostility to Mr Corbyn's leadership among his MPs, and the hopes of some that he could be removed, that in itself is a risk.

But the last few days may simply serve to widen the gap between Mr Corbyn's supporters in Westminster and beyond and most of the Parliamentary party - summed up balefully by one member of the shadow cabinet as the "weak fighting the weak".

Reshuffles are rarely clean, but this noisy, messy few days demonstrates that right now, Labour is a party struggling to come to terms with itself, and consumed by its own divisions.

Until that changes, the chances of the public giving Labour another chance seem slim indeed.

- Published14 September 2015

- Published4 January 2016

- Published5 January 2016