Is 'King Jeremy the Accidental' on the up?

- Published

- comments

There is an old blues standard with the lyric "I've been down so very damn long, this looks like up to me". By that measure, things are looking up for the Labour leader.

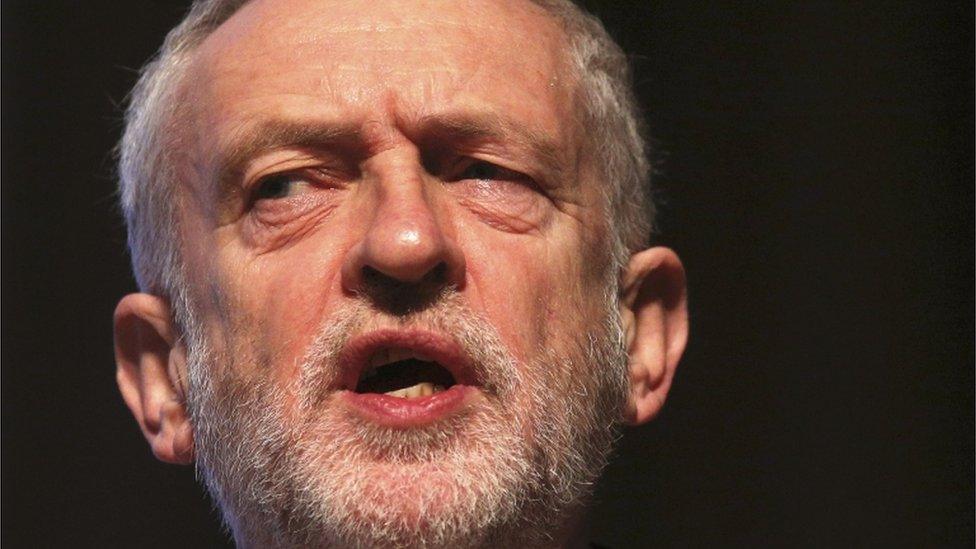

To the fury and frustration of many of his parliamentary colleagues, and the slack-jawed amazement of some lobby journalists, Jeremy Corbyn is still in the job after failing every test they have set him.

Perhaps, it says as much about them as about him.

Now the smoke has cleared away from the reshuffle, he has regained control over a key policy - Trident.

He was given a kind of standing ovation for a speech, external to a Fabian conference, which some described as his best yet.

And he survived a big interview with Andrew Marr, with only one headline mocking his naivety, external.

Perhaps most importantly, Len McCluskey the leader of the UK's biggest union, Unite, told me, on BBC Radio 4's World This Weekend programme, that to regard the May elections as a referendum on Mr Corbyn was ridiculous - he would be "allowed"' two or three years to prove himself.

These are all very low bars.

Mr Cameron and Mr Osborne are not quaking in their boots.

But they leave the Labour right with a huge conundrum - one insightful commentator, external has been musing recently on whether it should even want to do well in the coming elections.

Fanciful ideas circulate about MPs saying they have a mandate, external, because millions of people have voted for them, whereas Mr Corbyn and Labour members do not.

But basing a strategy around losing elections and formalising a split are more of a yardstick of desperation than practical politics.

Headline tug of war

Journalists and politicians based at Westminster see the world in a certain way, through a fairly narrow lens, and measure daily success and failure through a set of unwritten rules reached by instinct rather than reflection.

The soap opera of the Westminster village matters to those who adore the storyline.

It is often about a tug of war between positive and negative headlines, trials of strength over internal and external opponents, with all the fragility of narrative within a bubble.

Alastair Campbell kept tight control of New Labour's media image

One of the reasons Mr Corbyn attracts so much opprobrium from those whose orbit circles planet Westminster is he will not accept their measure of his worth.

He seems more concerned with remaking the Labour Party in his own image than winning applause from hostile crowds.

The climax of one of my favourite science-fiction novels by the late, great Iain M Banks, The Player of Games has the representative of a pan-species libertarian communist idyll of which Mr Corbyn might approve taking on a brutal, fascistic, authoritarian and warlike regime at a sort of violent hi-tech version of multi-dimensional chess.

He, unwittingly, plays their destructive game of conquest and revenge in a way that turns it into an artistic performance, a harmonious, complex ballet.

His opponents react with vast, speechless fury because he has done something much worse than beat them.

He has undermined their rules and their values.

This is not to say Mr Corbyn is about to do the same.

But Westminster's rules are not the only measure.

There is a similar level of mutual incomprehension.

And the Labour leader, with an equal lack of guile, is subverting the game itself.

It is not that Mr Corbyn does not play by the rules, so much as he simply disdains them, a debutant who turns up at the ball in torn jeans and slouches against the wall, sullenly refusing to join the dance.

New Labour's architects understood something obvious but rarely exploited until then - politicians are known to the great mass of voters only through the media.

A central part of their strategy was to seize control of the way their image and actions would be reported.

Jeremy Corbyn has brought a new approach to Prime Minister's Questions

The techniques varied from wooing to bullying, circumventing the hard questions to tackling them head on.

The message merged with the medium.

Mr Corbyn appears to be the very mirror image of this.

His speeches do not contain an obvious attention-grabbing new policy, briefed in advance.

Prime Minister's Questions is not a mano-a-mano trial of strength, envisaged through the lens of the next hour's headline.

Inside the serious personnel management of a reshuffle, there is no central message.

But in this he is, possibly unwittingly, following a central insight of Alastair Campbell and Tony Blair about media management - most people do not follow the details of politics, it is the broad image, a flavour, that comes across.

It could just work.

Mr Corbyn's dogged pursuit of policy and principle without fancy frills and theatrical lunges at the enemy does portray a certain earnest sincerity that clearly appeals to many potential supporters of the Labour Party.

Fans of principle

My unscientific analysis would suggest many Corbyn enthusiasts are not the Trotskyists of MPs' imagination but people disillusioned by Mr Blair and Gordon Brown, impelled by youthful enthusiasm or nostalgic remembrance for something with less "yah" and "boo" and more principle.

For often less than good or sensible reasons, "politician" has long been an insult - people who elevate tactics and electoral victory over higher purpose.

Not being like them, may not be seen as such a bad thing.

Labour grandee Margaret Beckett has warned the party faces big challenges

But the problem for the Labour Party is this may be enough to keep Mr Corbyn from being seriously challenged but not enough to win any new voters.

As Margaret Beckett's report, external makes clear, having an electable leader and a winning economic policy are central but not the only challenges.

The loss of Scotland, the collapse of working-class loyalty, English identity, an ageing population, the ideological challenges for the centre left are, on their own, big roadblocks on the path to power.

Piled up together, it is hard to envisage the sort of bulldozer that could shift them.

Mr Corbyn may not be the man for the job - but he is the man with the job, behind the wheel.

I have always found when kings and queens forged history fascinating.

They were often very ordinary people, without formal training, thrust into exceptional roles.

How they fared says much about human nature and politics.

But this is not true of modern democracies.

Indeed, it is not true of most modern dictatorships.

Stalin and Churchill were experienced media performers

Whether Stalin or Churchill, or indeed Neil Kinnock or Iain Duncan Smith, leaders have paid their dues, gained a patina of experience, during their far from inexorable and inevitable rise.

They have learnt the tricks of the trade the hard way, hard knocks filing off rough edges.

But this is not true of Mr Corbyn, who never planned to be leader, never thought he would be, and has not jostled colleagues for power and position.

The fervent republican King Jeremy the Accidental has little past history of cunning or compromise, just the guiding principle of a passionately held set of ideas.

We may need a different ruler to measure his rule - both its length and purpose.

- Published17 January 2016

- Published17 January 2016

- Published16 January 2016

- Published7 January 2016