Labour's tortured relationship with the nuclear deterrent it created

- Published

Clement Attlee is revered on the left as the father of the NHS and the welfare state. What is less celebrated, but no less true, is his role as the father of Britain's nuclear bomb.

It was Attlee, as Labour's post-war prime minister, who made sure Britain got its own "nuclear deterrent", committing millions to its development at a time when the country was technically bankrupt.

He did it in secret, without a debate in Parliament or the Labour Party, partly out of a desire to avoid damaging rows.

The rows would come soon enough - and are continuing to split the party more than 70 years later, as Jeremy Corbyn wrestles with the seemingly impossible task of reconciling its pro and anti-nuclear factions.

Attlee had his reasons for wanting Britain to become a nuclear-armed nation. He had just been elected prime minister when America dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, in August 1945.

He realised in an instant that the air raid wardens and fire engines that had fought to limit the damage done by Nazi bombs, were now useless in the face of the awesome destructive power of this new weapon. The only way to protect the population, he reasoned, was to have the ability to fight back.

"The answer to an atomic bomb on London is an atomic bomb on another great city," he wrote in a secret memo to a cabinet committee 22 days after Hiroshima.

This is the concept of a nuclear deterrent and "mutually assured destruction" in embryo.

'Whatever it costs'

But Attlee was no warmonger. He wanted to rid the world of the menace of nuclear war by handing control of the weapons to the United Nations, even arguing that information about the bomb should be shared with the Soviet Union.

"He immediately recognised the potential importance of nuclear weapons both for the conduct of war and for the conduct of international relations," wrote Len Scott, former professor of international history at Aberystwyth University in an essay on Labour and the bomb.

But at the same time, added Prof Scott, he believed that Britain must have its own bomb, a need that became more pressing when the Americans passed a law, in August 1946, preventing it from sharing atomic secrets with other nations, including its closest wartime allies Britain and Canada, whose scientists had worked alongside the Americans to develop the Hiroshima bomb at Los Alamos.

Debate raged in cabinet committees between those, like Chancellor Hugh Dalton, who argued that Britain could not afford a bomb, or the new V-force aircraft needed to deliver it, and those who argued that the country needed to keep its place at the top table and avoid being humiliated by the Americans.

"We've got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs," foreign secretary, and former trade union leader, Ernest Bevin, is reported to have told one committee.

"We've got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it."

Trident facts

Currently, the government is spending about 6% of its annual defence budget on Trident, the Ministry of Defence has confirmed

Trident was acquired by the Thatcher government in the early 1980s as a replacement for the Polaris missile system which the UK had possessed since the 1960s

An operational Vanguard class submarine carries 16 Trident missiles. There is one on patrol round-the-clock at all times

Each Trident missile is reported to have a potential destructive power eight times that of the first atomic bomb, which is estimated to have killed 140,000 people, and to have maimed many more, when it was dropped by the United States on Hiroshima in Japan on 6 August, 1945

Bevin's national prestige argument won the day - and it would surface again in 1957, when left-winger Aneurin Bevan surprised supporters by hitting back at calls for Britain to get rid of it nuclear weapons by telling that year's party conference the unilateralists were gripped by an "an emotional spasm" that would send a future Labour foreign secretary "naked into the conference chamber".

Labour's leadership argued at the time that Britain should only abandon its weapons if it could persuade other countries, such as China and France, to do likewise (persuading the Soviet Union and the US to disarm was seen as a non-starter).

But the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), formed in 1957, was growing in influence within the party, making the argument on moral grounds against weapons of mass destruction, with the Hydrogen bomb, a vastly more powerful weapon, recently tested by Britain, looming over the debate.

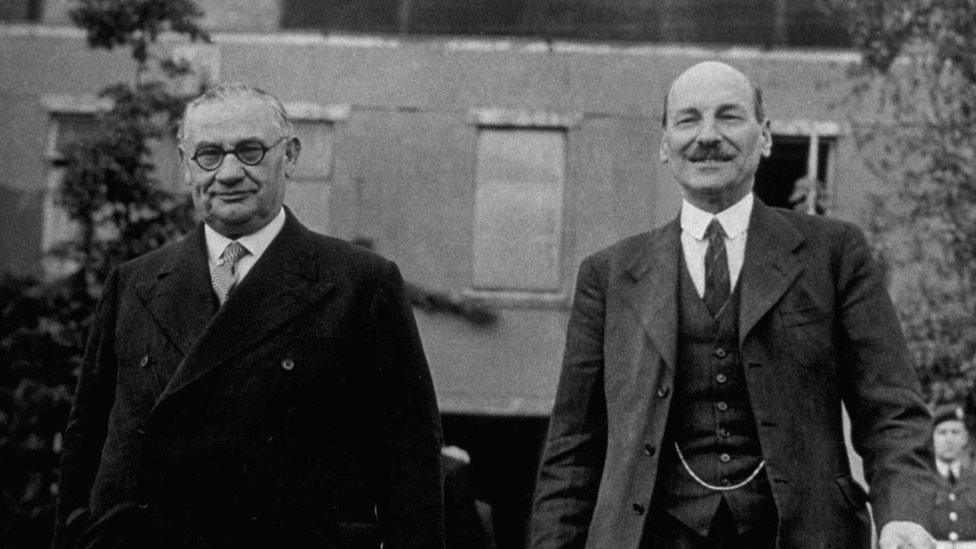

Ernest Bevin and Clement Attlee wanted an independent deterrent

CND's calls for Britain to unilaterally scrap its weapons briefly became party policy, before being overturned at the 1961 conference.

Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell's successor Harold Wilson fought the 1964 general election questioning Britain's nuclear deterrent, declaring in Labour's manifesto that Polaris, American nuclear weapons to be fitted to British-built submarines under an agreement brokered by Tory PM Harold Macmillan, "will not be independent and it will not be British and it will not deter".

Attlee was even wheeled out, in a party election broadcast, to denounce the independent deterrent as a "nonsense".

Soviet invasion

But the manifesto did not include an explicit commitment to abandon Polaris, just reassess the deal with the Americans, and although Wilson reduced the number of submarines from five to four, and brokered a non-proliferation treaty, Polaris became operational in 1968, beginning the round-the-clock patrols that continue to this day.

The left felt betrayed by Wilson and when Labour unexpectedly went into opposition after the 1970 general election the party renewed its commitment to scrap Polaris and end moves towards a new generation of nuclear weapons, neither of which it did when it returned to power in 1974.

When Margaret Thatcher entered Downing Street in 1979, the nuclear issue erupted with renewed ferocity in the Labour Party, against a backdrop of escalating tensions between NATO and the Soviet Union.

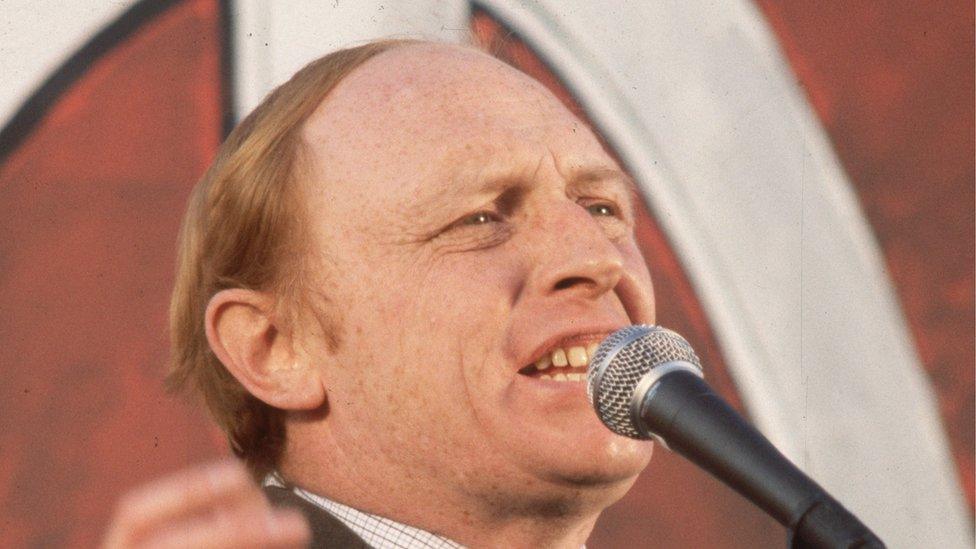

Neil Kinnock was a regular speaker at CND demonstrations

It had now become a hugely symbolic issue for the party, a key dividing line between the left and right, who would eventually break away to form their own party, the SDP, to fight the 1983 general election.

Then Labour leader Michael Foot, a founder member of CND, was a unilateralist, who also vowed to remove US nuclear weapons from British soil. His successor Neil Kinnock, was also a unilateralist, although he would drop the policy after losing the 1987 election, arguing that the best way to achieve a nuclear-free world was through negotiation between nuclear-armed nations.

Kinnock had united the party behind scrapping nuclear weapons by arguing that the money spent on Trident - the replacement for Polaris - should go towards bolstering Britain's conventional forces instead, but he still faced accusations from the Conservatives that he was "soft" on defence and would make Britain a target for Soviet invasion.

There were also questions about how Labour could scrap its weapons on moral grounds yet still expect to shelter under America's "nuclear umbrella" and how it could remain a member of nuclear-armed NATO.

Cold War relics

Tony Blair banished unilateralism from New Labour's vocabulary, along with other policies thought to be harming its credibility with centre ground voters.

But the nuclear issue still had the power to split the party - in 2006 he faced his biggest rebellion since the Iraq war over plans to push ahead with a replacement for Trident, when 88 Labour MPs voted against the government. The backing of the Conservatives ensured Blair won the vote convincingly.

His argument to MPs was that Trident was the "ultimate insurance" and that it would be "unwise and dangerous" for Britain to unilaterally give up its nuclear capability.

One of the rebels who spoke against Blair that night was veteran backbencher and CND stalwart Jeremy Corbyn, who quoted the mayor of Hiroshima in his speech, who had "pleaded" with Britain not to "develop a new generation of nuclear missiles".

"We face an important decision tonight," said the Islington North MP.

"Either we endorse this vast expenditure, or we encourage a public debate that I believe will come down on the side of sanity, sense and peace in the world, and we do not go ahead with this vast expenditure that can lead only to a more dangerous world."

The idea that Corbyn would one day succeed Blair as Labour leader, and re-open the party's debate about unilateral disarmament, would have seemed pretty far-fetched to the MPs in the Commons chamber that night, including Corbyn himself. But he has now has the chance he has long craved to persuade the public of the "sanity" of his case.

Labour has tended to be gripped by internal rows about scrapping nuclear weapons when it has been in opposition for some years, only to maintain the deterrent when it returns to power.

But, as the party's resurgent unilateralists point out, this is the first time Labour has seriously debated the issue in a post-Cold War context. It is a very different world to the one facing Attlee in 1945.

The challenge for Labour's defence review, headed by Emily Thornberry, is to avoid the Cold War thinking that still tends dominates both sides of the debate and see the issue with fresh eyes.

Given the party's tortured history, that will not be easy.

- Published9 February 2016

- Published23 May 2017