Investigatory Powers Bill: May defends surveillance powers

- Published

Home Secretary Theresa May has defended controversial new surveillance powers as MPs debated them for the first time.

The Investigatory Powers Bill, external will force the storage of internet browsing records for 12 months and authorise the bulk collection of personal data.

Mrs May said the measures were needed to keep the public safe and would uphold "both privacy and security".

Labour and the SNP said they backed the bill in principle but would withdraw support without substantial changes.

Labour's stance was branded "gutless" by the Lib Dems, who oppose the legislation.

The bill's second reading - where it was backed by 281 votes to 15 - gave MPs their first chance to debate it in the House of Commons. It represented an early step in a long parliamentary process which will see the details of the measures scrutinised at greater length over the coming months.

Shadow home secretary Andy Burnham said Labour would work constructively with Mrs May to get the legislation through Parliament but that "substantial changes" were needed to ensure the right balance "between collective security and individual privacy in the digital age".

Labour abstained at second reading and will be seeking amendments including a specific "presumption of privacy".

Andy Burnham says he is not giving the home office a 'blank cheque'

"We need new legislation but this bill is not yet good enough," he said. "Simply to block this legislation would, in my view, be irresponsible. It would leave the police and security services in limbo... We must give them the tools to do the job."

The proposals have already been significantly amended after a draft bill last year was heavily criticised by three parliamentary committees.

The government may be forced to give further ground if it is to get the law on to the statute book by the end of the year as it wants, although it is not expected to meet significant resistance until the bill reaches report stage and then goes to the House of Lords.

'Bulk powers'

Mr Burnham called for the use of surveillance powers to be limited to more serious investigations and for greater clarity on who can use them.

He said he did not see why agencies such as the Gambling Commission or the Food Standards Agency should have access to people's internet records, and said he would be calling on Mrs May to "severely reduce" the list of agencies who would get the new powers.

He also called for an independent review of "bulk powers" - the sweeping up of vast quantities of internet data and the collection of personal information from databases by the security services.

"I want a bill that helps the authorities do their job but protects ordinary people from intrusion and abuse from those in positions of power," he added.

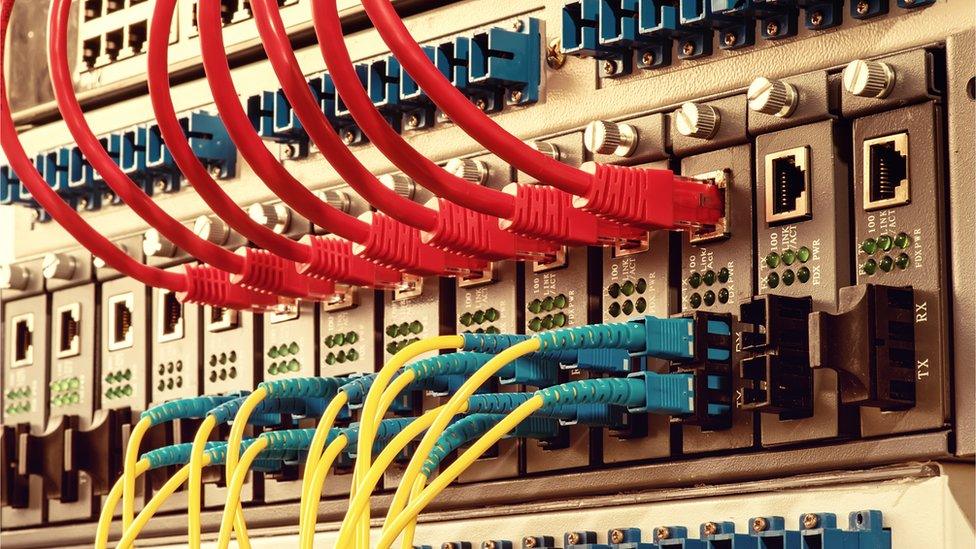

The IP Bill seeks to place new obligations on telecoms companies

Mrs May has said Britain's spies must continue to be allowed to hack into foreign computer networks, under so-called "bulk equipment interference warrants", as this was "a key operational requirement for GCHQ".

She told MPs that bulk powers had played a significant role in every major counter-terrorism investigation over the past decade, including seven terror plots foiled in the past 18 months, and in responding to the bulk of cyber attacks against UK interests.

Operational requests for such information, she said, would have to be approved by a judge as well as the minister responsible under a regime of "robust and consistent safeguards".

But Conservative MP Owen Paterson, a former Northern Ireland secretary, said elected politicians accountable to Parliament and the public should be exclusively responsible for granting warrants.

The SNP said they were in favour of "targeted surveillance" but many of the powers being sought were of "dubious legality".

"We will work with others to try and amend the bill extensively," Joanna Cherry, the party's home affairs spokeswoman, said. "If the bill is not amended to our satisfaction, we reserve the right to vote it down at a later stage."

'Not fit'

The Lib Dems blocked Mrs May's previous attempt to legislate in this area, which was dubbed "the snoopers' charter", when they were part of the coalition government.

Speaking in the debate, former leader Nick Clegg said the bill was an improvement on previous proposals but was "not in a fit state" - telling MPs that it was still predicated on a "dragnet approach" to data retention and the powers it sought to grant were "formidable and capable of misuse".

"The implications of this are very big indeed," he said.

"It is that the government believes as a matter of principle that every innocent act of communication online must leave a trace for future possible interrogation by the state. No other country in the world feels the need to do this apart from Russia."

UKIP MEP Steven Woolfe told the BBC's Daily Politics he was "deeply concerned" by the Investigatory Powers Bill, saying it "could put us into an extreme position of monitoring our citizens".

Edward Snowden, the former CIA analyst turned surveillance whistleblower, said he was closely following Tuesday's debate. He tweeted, external: "Britons, note how your MPs vote today on IPBill. A vote in favour, or abstention, is a vote against you. "

And Amnesty International warned that "wide-ranging snooping powers" were being rushed through parliament at "break-neck speed".

- Published2 March 2016

- Published10 March 2016

- Published9 February 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published5 November 2015

- Published11 February 2016

- Published1 February 2016

- Published8 January 2016

- Published4 November 2015

- Published22 December 2015