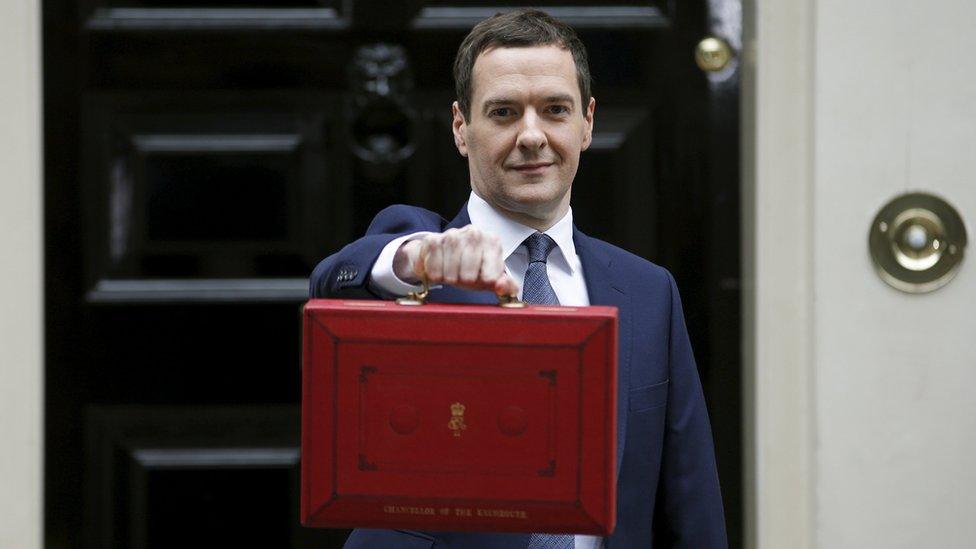

No longer the 'lucky chancellor'?

- Published

If George Osborne was the "lucky chancellor" in November when the Treasury found an extra £27bn down the back of the Commons green benches, what will he be today?

How does he respond practically and politically to the fact that the numbers he based his plans on at the Spending Review have turned out to be wrong?

Fess up

And not just those numbers, but much of the case that he'd been building in the year before feels, well, misplaced, now - that we were on our way "out of the red and back into the black", he had "fixed the roof" while the sun was shining, whichever Osborne metaphor you want to choose.

As my colleague Kamal Ahmed's written here, the backdrop is different. So first, George Osborne is going to have to fess up - the pages and pages of numbers the independent Office for Budget Responsibility provided as the basis of his sums won't add up anymore.

We know too - as he told me a few weeks ago - that means extra government cuts are likely, probably an additional £4bn billion a year by 2020.

So more cuts are on the way, on top of six years of spending reductions that have hit some families extremely hard.

School reforms

But the government's announcement today on academy schools, and the fact the chancellor, not the education secretary, is making it, suggests something else too.

Numbers 10 and 11 are determined to make us believe they are interested in much more than just sorting out the books - they're not just cutters, but reformers too.

George Osborne will say all state schools will be forced to become academies

Even though those plans will cause strong complaint, they are part of George Osborne and David Cameron's plans to achieve more than just close the gap between what the government spends and takes from all of us in taxes - although they know that's proving hard enough.

And while the numbers are certainly worse than Number 11 had hoped, and the catchily-titled "downward revisions" will grab many of the headlines, George Osborne's political brain may tell him that economic changes have not knocked the (notoriously unreliable) predictions so far off course that it is worth any enormous deviation from his overall strategy.

So the chancellor, albeit in rather more sombre tones, is likely to echo his previous audacious claims that a Conservative government that is making significant cuts to state spending is composed of "the mainstream representatives of the working people".

Huge ask

He has been doing the job for six years now, and knows the dangers of a Budget that goes wrong, and one that goes with a bang. But with the Conservatives' ambitions, and his own, in mind, he is unlikely to miss the opportunity to make that case again.

Despite the shadow chancellor's new credo that aligns his hypothetical plans for tax and spend closely to those of Labour's recent past, even before George Osborne is on his feet John McDonnell is demanding that he stop the cuts.

Jeremy Corbyn will respond for Labour

One of the quirks of Budget day is that it will be for Jeremy Corbyn, not Mr McDonnell, to make that case, responding to Mr Osborne.

That is a tall order for any opposition leader. For Jeremy Corbyn, who enjoys huge support from the party's membership but not much from those sitting on the benches behind him, it is a huge ask.

But the opposition that really troubles Mr Osborne right now is those on his own benches. He'll be more interested in how they, and the public, respond - and if he's not the "lucky chancellor" any more, what they'll be calling him by the end of today.