Conservatives, Europe and the risks of a disunited party

- Published

Divisions over Europe which came to a head in the early 1990s have remained unreconciled

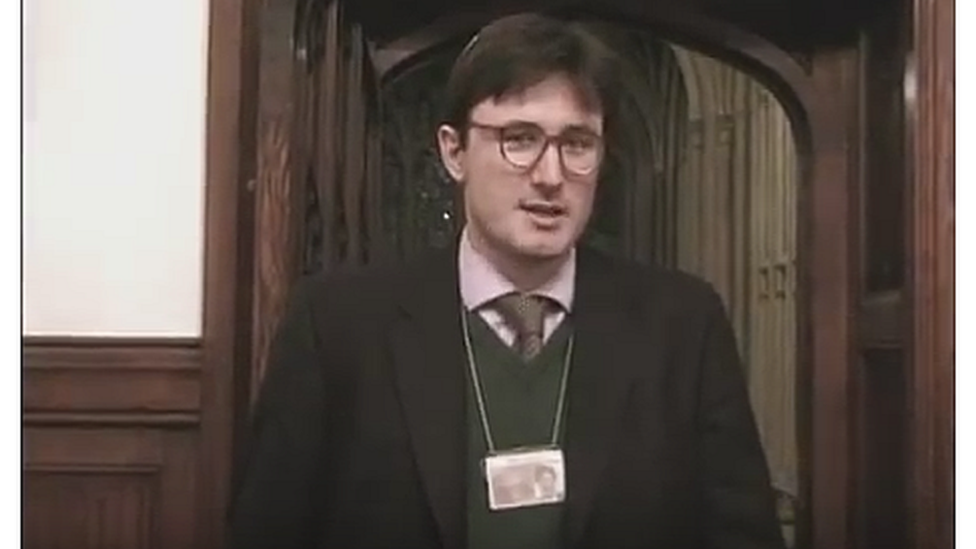

I have come full circle. In the early 1990s, I arrived at Westminster as a young reporter, there to help chronicle the decline of the Conservative Party for The Times.

The then prime minister, John Major, had a small parliamentary majority and large parliamentary problem: a party divided to the core over Britain's membership of the European Union, divisions that were under laid by deep-set personal feuds, all the while potential successors for the leadership circled and plotted and agitated against Downing Street.

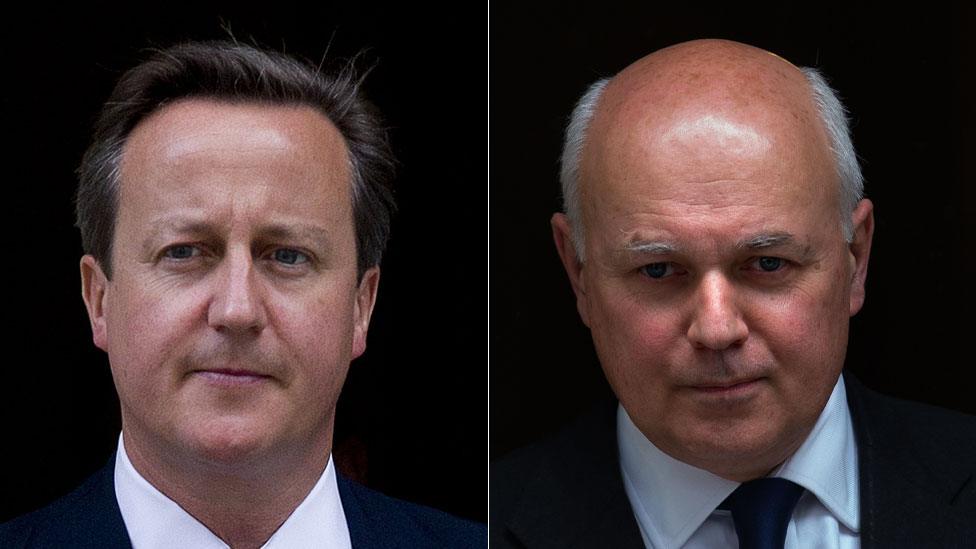

One key player in all this was a young Eurosceptic MP called Iain Duncan Smith. More than two decades on, as I prepare to leave Westminster, I am overwhelmed by a wave of nostalgia as the years fall away.

There are, of course, limits to the parallel. There is no single piece of legislation like the European Communities (Amendment) Bill - the so-called Maastricht Bill - around which battle can be fought. The Tory party is no longer gripped by a debilitating grief over the political matricide it had just carried out against Margaret Thatcher.

But the divisions over the EU remain as strongly held as ever, and they are divisions that have remained unreconciled ever since.

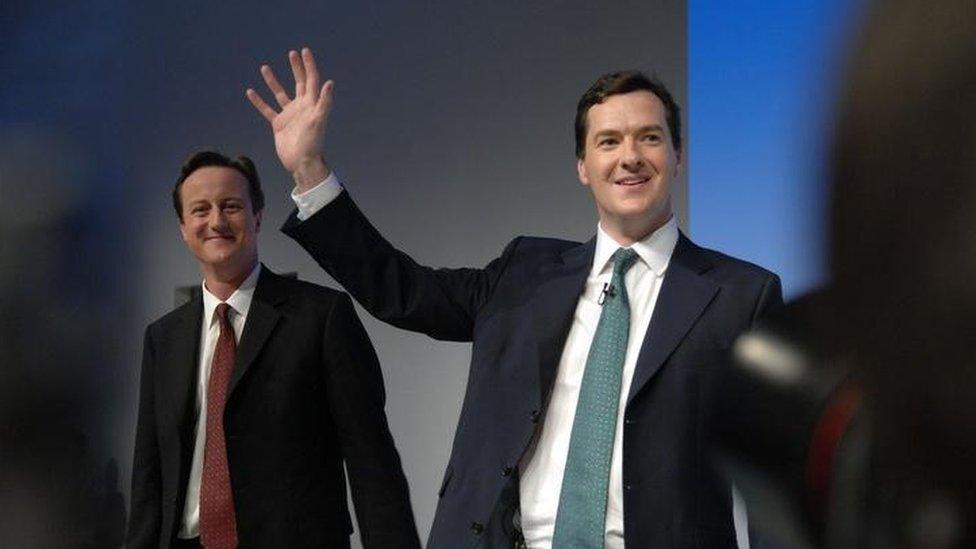

For the last few years, David Cameron has held those divisions in check by the promise of a referendum. The arrival of the campaign has unleashed those divisions which can no longer be ignored. And it has done more than that.

The freedom the prime minister has given ministers to argue for so-called Brexit has legitimised dissent against him and George Osborne, dissent that has spread to issues other than Europe.

Some Tory MPs have got a taste for speaking publicly against their leadership without the usual punishments and without the usual pressure from a competent opposition.

Tory purpose

So enter Mr Duncan Smith and his dramatic resignation. The former work and pensions secretary questioned a narrow piece of policy, namely whether a certain disability benefit should be increased less quickly than the government had promised at the cost of a fraction of a per cent of the government's budget.

But more importantly he questioned the very purpose and character of the modern Conservative Party, whether it was fair, compassionate, whether we were "all in this together". And he attacked the chancellor of the exchequer directly in ways that no minister or MP had dared before.

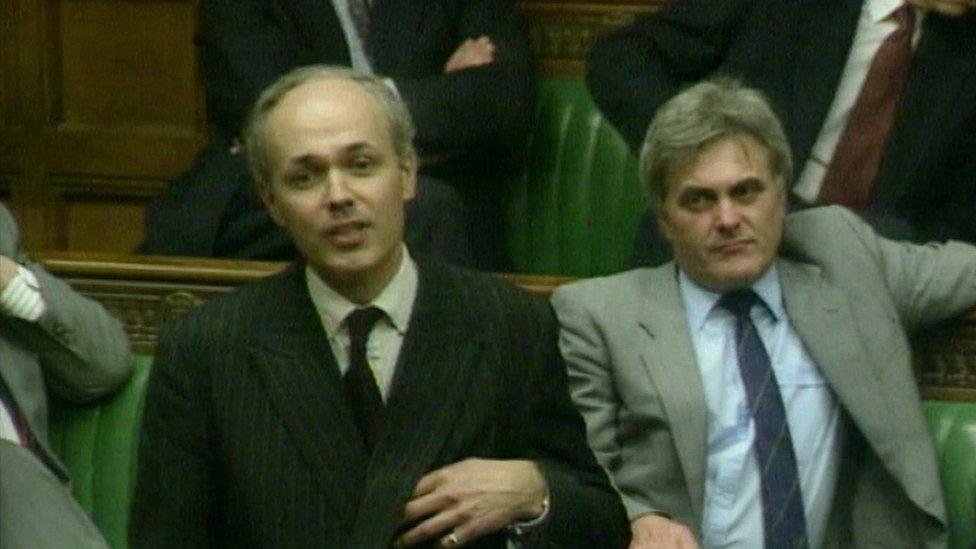

John Major's fight with Eurosceptic Tories in the 1990s culminated in a leadership contest

That explosive assault, in the eyes of some Tory MPs, effectively declared open season on Mr Osborne. Long-held, deeply-felt animosities have come to the surface, frustrations about his style of management, his repeated strategic errors, and the smugness of his clique of supporters, known as FOGs or "friends of George".

Here are just a few quotes from Tory MPs I spoke to about Mr Osborne:

"He always treats you as if you are his social and intellectual inferior. Even if that is true, he should not let it show".

"George has got where he has by either bullying or rewarding people. Once the influence declines he has no mates to fall back on. It is all very transactional."

"IDS makes me proud to be a Conservative. I don't feel that about George."

Frustration over referendum rules

For some Tory MPs, these are latent gripes they just feel more liberated to express in the current circumstances. For others, this is clearly an opportunity to damage Mr Osborne ahead of any future leadership contest.

There has always been a minority who have felt excluded and marginalised by the Cameron/Osborne hegemony, which let us not forget, is now more than a decade old. That minority will not miss out on an opportunity to try to "kill George", as one MP put it.

These generically anti-Osborne MPs have been joined by those campaigning to leave the EU, many of whom are deeply frustrated by the way the chancellor and the prime minister have behaved in the run-up to the referendum. They believe Mssrs Osborne and Cameron have tried to rig the rules in favour of the Remain campaign.

Resentments have built up over the decade in which David Cameron and George Osborne have led the party

They believe this despite Downing Street giving way to their every demand over the referendum question, the date, the rules for civil servants, the freedom of ministers to stay in office while opposing the government, and their ability to do so immediately after the renegotiation deal was agreed a few weeks ago.

As one pro-Brexit ex-minister said: "We played five and won five."

Despite all those concessions, the Brexiteers still feel very strongly that there is not a level playing field for the Leave camp and they blame Mr Osborne.

Some seem to resent being campaigned against by Downing Street with the same sense of puzzled hurt that Liberal Democrat ministers felt when the Conservative Party opposed and defeated their plans for electoral reform in 2011.

Question of succession

We must also add a further ingredient to this ferment. Ever since David Cameron told me in his kitchen last year that he would serve only one more term, his authority has been slowly waning.

He legitimised discussion about a time when he would not be around. Until recently, many Tory MPs thought that his successor would most likely be George Osborne. But fewer of them think that now and they are looking around for alternatives.

One MP told me that Tory leaders often emerge from nowhere to stop another candidate from winning. He described how John Major was chosen to stop Michael Heseltine, and David Cameron to stop David Davis.

The outcome of Tory leadership contests are often unexpected

He said: "The question now is who is the person to stop Boris Johnson becoming leader? What about the woman who has said nothing and done nothing throughout this whole affair - Theresa May?"

I cite this merely as an example of the slightly frenzied leadership speculation that is taking place, speculation that already assumes that Mr Osborne is dead in the water.

And what of the largest number of Tory MPs, the younger members who arrived in 2010 and 2015? One said: "Most MPs are just thinking, shit, this can't go on, this could make Corbyn happen. They don't want to attack IDS, they don't want to attack Osborne, they just want all this to go away."

Many of the new intake know what it was like in the early 1990s, they know how much damage it caused to their party, and they don't want to see it again.

Mr Osborne's friends insist that he can bounce back and note that if people vote to remain in the EU, it could be several years before a leadership contest. They say his immediate focus is on winning that referendum.

James Landale reported on Tory splits on Europe for The Times in the 1990s

The short-term risk is that a government which was elected, in part, because of its reputation for unity and economic competence is now seen as anything but by an electorate about to go to the polls. Voters rarely support divided parties that are gripped by an existential identity crisis.

But if there is one echo down the decades that I sense most strongly it is this: that now, as in the early 1990s, there are some Conservative MPs who feel so passionately about the issue of Britain's membership of the European Union, that it exceeds their passion for keeping their party in power.

Iain Duncan Smith felt so passionately about his opposition to disability benefit cuts that he was prepared to give up power personally and risk damaging his party.

That passion is matched by other MPs over the EU. Night after night in the 1990s I would stand in the press gallery of the House of Commons at the 10pm vote, watching Tory MPs rebel against and undermine their leadership out of utter conviction that Britain's national interest was being damaged by a treaty that deepened our integration within the EU.

That fractious mood, that air of rebellion, is once more alive on the Tory benches and it is a mood full of danger and portent.

- Published21 March 2016

- Published21 March 2016