Testing times ahead for Universal Credit

- Published

The government's scheme to overhaul the welfare system has been the subject of much scrutiny in Westminster, but now the same is happening outside a north London job centre.

Two claimants become animated as they wait for the next part of their appointment inside.

No, they don't want to do an interview - but yes, they have something to say about Universal Credit - the single payment streamlining six current in-work benefits.

One woman was supposed to sign up to it, she says, only to be told she wasn't eligible - and doesn't know why.

Another thinks paying housing costs directly to claimants is a terrible idea which some people will find impossible to manage.

Delays

It is hardly a representative survey about one of the biggest changes to benefits since the start of the welfare state, but it tells you something important: Universal Credit has arrived.

It is now up and running in 690 jobcentres and will be available for all single jobseekers in all jobcentres from the end of April.

Almost 405,000 people have now made a claim for Universal Credit.

New Work and Pensions Secretary Stephen Crabb has stressed his commitment to Universal Credit

After delays, IT problems and an entire "reset" of the system - the piecemeal, if deliberately slow, implementation has begun.

But that is the simpler part; the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) now has to deliver the changes to 20 times that number of people, many of whose cases will be far more complex, in a project already running several years late.

And it no longer resembles the scheme originally conceived under former Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith, at a cost of £1.7bn to implement.

Universal Credit was meant to bring "radical changes" to people's real incomes and incentivise them to move off benefits and into work, according to David Finch, a former economic analyst at the DWP.

"But... the strength of the improved incentives it was meant to bring have been gradually eroded," he says, speaking in his current role as a researcher at the Resolution Foundation.

There have been significant tensions between the Treasury and the DWP over its cost.

Last year the government announced funding cuts to the universal credit "work allowance" - reducing the amount people can earn before benefit payments are withdrawn.

'Great idea'

Labour believes those changes have left the project in a perilous situation.

"Universal Credit is a great idea that unfortunately is running the risk of being stillborn as a result of the cuts that Osborne and Iain Duncan Smith oversaw," says Labour's work and pensions spokesman Owen Smith.

"It should make work pay for people but unless (new work and pensions secretary Stephen Crabb) reverses the cuts to the work allowance and restores the work incentives it's going to leave millions of people worse off."

Universal Credit was a cornerstone of Iain Duncan Smith's reforms

Iain Duncan Smith's resignation in March came amid a febrile atmosphere over planned government cuts to disability benefits - later reversed - resulting in the effective protection of the welfare budget at current levels.

The former cabinet minister criticised the "cutting away and eroding" of universal credit and an "assault" on its incentives system while he was in office.

But those close to Mr Duncan Smith regard other criticisms of Universal Credit as over-played and a "media narrative".

One source said the project was now "wholly owned by the civil service" and that there was no concern that Mr Duncan Smith's departure compromises it.

Certainly the speech by his successor Stephen Crabb confirmed that.

Mr Crabb said he was "absolutely committed" to the reform, describing it as "the spine that runs through the welfare system".

So where does all this leave us?

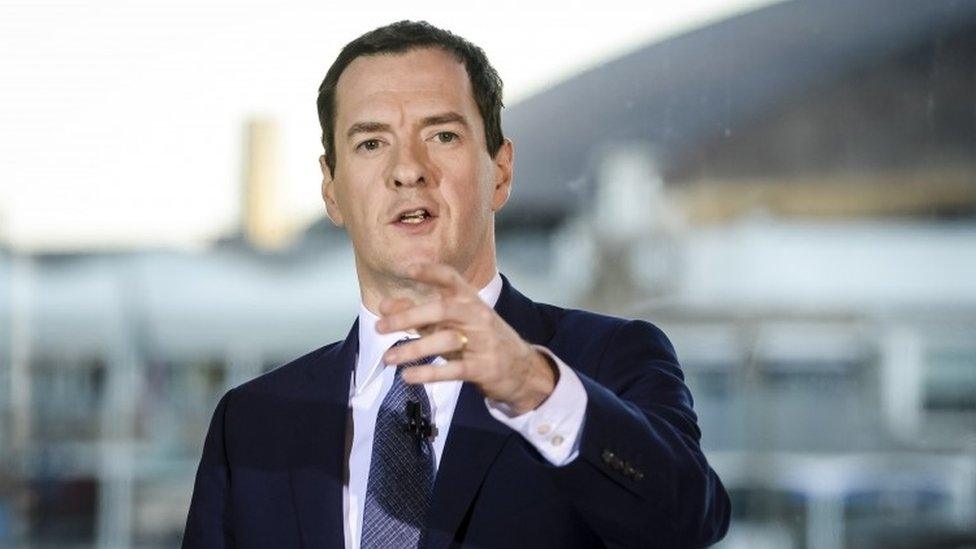

George Osborne's Treasury clashed with Mr Duncan Smith over cuts to the welfare budget

Despite many people losing out after last year's changes, the Institute for Fiscal Studies thinks the objective of Universal Credit remains broadly intact - some of the worst disincentives to moving off welfare and into work will be gone under the new system.

Government officials claim it will help generate £7bn in economic benefit each year and say it will "revolutionise" welfare.

But its biggest challenge may lie not in its politics or even divided opinions over its funding, but in its delivery.

In May it will start to be made available to all types of new claimants, including those on ESA illness and disability payments where perhaps greater political sensitivity lies.

The full service will be available at five new job centre areas per month, ramping up to 50 a month in 2017.

These will be testing times for a project aiming to reach eight million households by the end of this parliament.

- Published15 February 2015