Politics in the age of the instant insult

- Published

Dennis Skinner was expelled from the Commons for insulting the prime minister

The Beast's beastliness falls well short of savage these days, and generates only faux outrage in the stilted setting of green benches.

Veteran Labour MP Dennis Skinner, long nicknamed "the Beast of Bolsover" has been chucked out of the chamber, external for calling the prime minister "Dodgy Dave".

While Mr Skinner's fury is doubtless genuine, he has become the establishment's licensed jester, the undignified part of the constitution.

His jibes are as nothing compared with the complaints of some right-wing Labour MPs about the way they have been treated by activists, external.

And they hardly raise the temperature in the same way as tweets praising Hitler, external.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a man who wants to become president is calling his detractors, particularly if they are women, ugly, dogs, dummies and clowns, although not always at the same time.

Far more elegant, and I would guess far more upsetting to the target, are Petronella Wyatt's remarks on the Chancellor George Osborne, external, a man she says she likes: "His complexion is Eastern, with the fish-belly pallor of Vlad the Impaler. His eyes have a Mongolian slant and his voice the twang of a Gypsy's zither."

Despite Jeremy Corbyn's call for a new politics, has it actually become cruder and ruder than ever before? Maybe not.

Churchill called Ramsey MacDonald "the boneless wonder" and Stanley Baldwin "that great turnip", external.

Churchill's choice insults:

On Labour Prime Minister Clement Atlee: "A modest man, who has much to be modest about"

On Labour Chancellor Stafford Cripps: "There but for the grace of God, goes God"

On his predecessor as Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain: "He looked at foreign affairs through the wrong end of a municipal drainpipe"

On World War Two commander Gen Montgomery: "In defeat unbeatable, in victory unbearable"

On 19th Century Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone: "Mr Gladstone read Homer for fun, which I thought served him right"

According to a book, external I'm reading at the moment, James II was insulted to his face by one unhappy subject, who said he was an "ugly lean-jawed, hatchet faced, Popish dog".

His successor William of Orange fared little better - one gentleman of Holborn was fined for observing the new king was "a rogue and a son of a whore".

But politicians and public figures have to do better than mere abuse.

While I have only the vaguest idea what the 18th Century Prime Minister Lord North, external looked like, Horace Walpole's, external description makes me giggle.

Lord North and his rolling eyes

"Two large prominent eyes that rolled about to no purpose (for he was utterly short-sighted) a wide mouth, thick lips and inflated visage, gave him the air of a blind trumpeter," Walpole said.

"A deep untunable voice which, instead of modulating, he enforced with unnecessary pomp, a total neglect of his person, and ignorance of every civil attention, disgusted all who judge by appearance."

Of course, the insults that weather well are those that lace venom with wit, external, and, better still, insight.

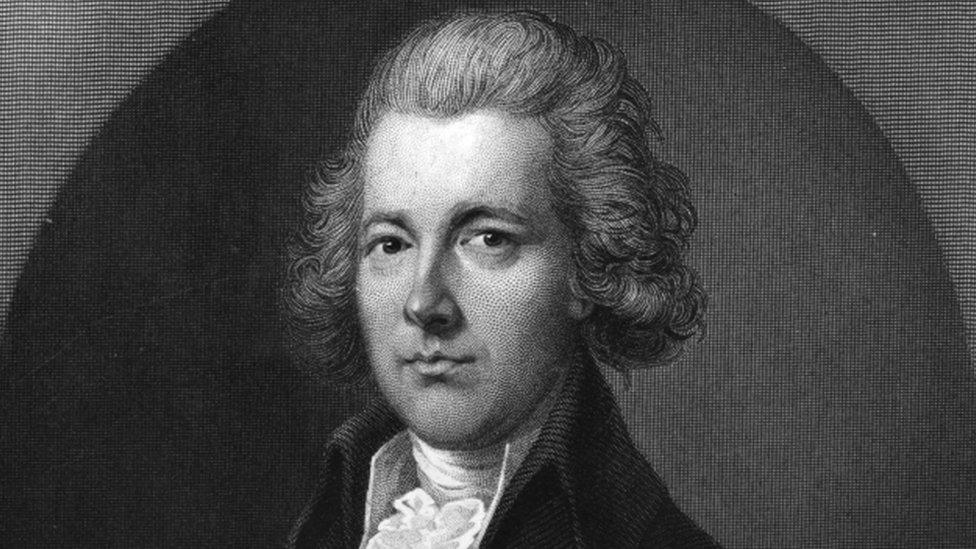

The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's observations on Pitt the Younger may fall short of poetry but strike to the heart of that remote, odd and brilliant man.

Coleridge said: "He has patronised no science, he has raised no man of genius from obscurity; he counts no prime work of God among his friends. He has no attachment to female society, no fondness of children, no perception of beauty in natural scenery; but he is fond of convivial indulgences, of that stimulation which, keeping up the glow of self-importance and the sense of internal power, gives feelings without the mediation of ideas."

Perhaps, pithy is better. Told by Lord Sandwich he would die either on the gallows or of the pox, radical MP John Wilkes, external replied: "That depends, my Lord, whether I embrace your mistress or your principles."

Not only smart but short enough to fit on Twitter.

But there lies a pointer to what may have changed.

Social media

I am constitutionally against hand-wringing over changes wrought by technology, or accusations the world these days is going to hell in a handbasket, but social media has made an impact on the public mood.

First, the restrictions on Twitter make it ideal for recommending and linking to longer articles and blogs.

But they do not encourage reasoned debate, and instead summon the mood of the mob.

A passing thought is entombed in text, the bad-tempered growl over a news item transmogrified into a hail of arrows shot into a victim.

Serious harassment, external has become so commonplace, it has given rise to a new lexicon of offence, from "flaming" to "trolling".

William Pitt the Younger was the object of Coleridge's scorn

Much less seriously, I can't be the only journalist who feels a bit disgruntled tweets attacking my work for bias or stupidity never delve in to identify the particular cause of offence.

Abuse has become the point, rather than simply the flashy thunderhead of an argument.

If you reply, it gets worse. Twitter exchanges, through their very brevity, get more heated. Email correspondence (or the even more old-fashioned sort) tends to lower the temperature and even lead to greater understanding.

Social media also encourages the herding together of like-minded people, who reinforce each other's values, refusing to listen to the other side.

The less they listen, the less they understand, the greater the reason to credit their opposition with base motives.

There is no point wondering if their values might be valid or their views worth considering - they are simply "sons of whores" or "hatchet-faced dogs.".

The mobs move through the virtual city, and all that can be clearly heard through the tumult are curses and imprecations.

Social media can be a friend of the instinctively clenched fist.

Reaction is instant - swifter than thought - with no time to mull, reflect and debate, and with no need to put a human face to a hated meme.

Such reactions stay largely in the virtual realm - but they are the enemy of the sort of politics that seeks resolutions and solutions to often complex problems.