Press regulation: What you need to know

- Published

Since the Leveson Inquiry was set up in 2011 - days after the News of the World newspaper closed amid the phone-hacking scandal - the issue of how to regulate the press industry has been fiercely debated.

As culture secretary, John Whittingdale's job is to regulate newspapers and he is currently overseeing a whole new regulatory framework under consideration in the wake of the Leveson Inquiry into press standards.

What's the background to press regulation reform?

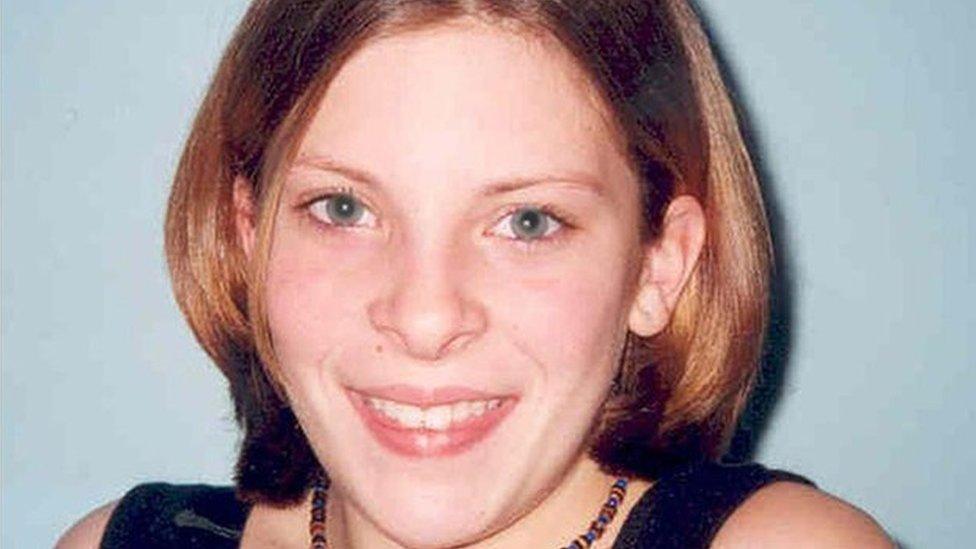

Milly Dowler, 13, was murdered in 2002. Her phone was later hacked by a private detective working for the News of the World

In 2011, it emerged that thousands of people, from celebrities to families of murder victims, had been victims of phone hacking by the now-defunct News of the World.

In response, Prime Minister David Cameron set up a public, judge-led investigation - the Leveson Inquiry - to examine the culture, behaviour and ethics of the press.

After hearing from numerous high-profile witnesses, Lord Leveson recommended newspapers should continue to be self-regulated - as they had been by the Press Complaints Commission - but that there should be a new press standards body created by the industry, backed by legislation, and with a new code of conduct.

The inquiry specifically focussed on the press, not into the media more generally. Broadcasters are regulated by Ofcom, which is backed by law.

What happened after the Leveson Inquiry?

In 2013, the then main political party leaders, David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband, agreed to set up a new press watchdog by Royal Charter.

It would have the power to impose million-pound fines on UK publishers and demand prominent corrections and apologies from UK news publishers, they said. Newspapers who refused to join the new regulatory regime would be liable - potentially - for hefty damages if a claim was upheld against them.

The press kicked back, saying the final draft of the Royal Charter plan was neither "voluntary or independent", and formed its own regulator, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso), with wider powers than previous bodies.

Why a Royal Charter?

David Cameron - uncomfortable with the idea of state interference in the press - rejected the idea of legislation to underpin the new system of regulation.

The compromise was the Royal Charter - an unlikely way to regulate the press. It is often described as a medieval form of documentation, used to set up universities.

The Royal Charter itself mainly sets out the workings of the body that is supposed to guarantee the self-regulator does its job properly.

But despite what one paper called its "flummery" the government spotted advantages to a Royal Charter. While an act of parliament can be amended with a simple majority, it was possible to insert a clause in the Royal Charter requiring any changes to be approved by a two-thirds majority.

What are the arguments over press regulation?

Campaigners tentatively welcomed the Royal Charter plan, saying it would protect the public against the worst abuses of the press.

However, the newspaper industry raised concerns that it would give politicians too much power. The Newspaper Society said it was tantamount to "state-sponsored regulation".

What's the situation now?

Labour have called for Culture Secretary John Whittingdale to "recuse" himself from decisions relating to press regulation

The Royal Charter was approved by the Queen in October 2013. However, publishers have largely chosen not to sign up to the voluntary system, sticking instead with their own regulator Ipso.

A key part of the Royal Charter plan was a law requiring publishers to pay both sides' costs in a privacy or libel case, even if they won - unless they signed up to the official press regulator.

This has been passed by Parliament - as section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, external - but still needs to be signed off by Culture Secretary John Whittingdale.

Victims of press intrusion have accused the government of breaking its promise over regulation.

Mr Whittingdale says it is "under consideration" and has told newspaper editors he questions whether this legal change will be "positive" for the newspaper industry.

Labour's Maria Eagle says Mr Whittingdale must "clarify exactly why he no longer believes" section 40 of the act should come into force.

Labour has now also called for Mr Whittingdale to withdraw from press regulation decisions after it emerged four newspapers were aware of his past relationship with a sex worker, but did not run the story.

What next?

While the first part of the Leveson Inquiry has finished, a second stage looking at the relationship between the press and the police is yet to come.

It was put on hold until all criminal and legal proceedings linked to the phone-hacking scandal were completed - although there have been suggestions that it may be shelved altogether.

The major phone-hacking trials of News International journalists concluded in 2014.

Labour has demanded the second stage goes ahead, but Downing Street says no decision has yet been taken about whether to continue with the inquiry.

According to a House of Lords report, external, the first stage of Leveson cost £5.4m.

- Published13 April 2016

- Published13 April 2016