EU referendum: Did 1975 predictions come true?

- Published

Dr. Robert Saunders: "It's like looking in a mirror...everything is inverted".

Britain voted by a margin of two-to-one to stay in the European Economic Community, as the EU was then known, in a 1975 referendum. How many of the things the defeated Out campaign were warning about have come true?

Through the looking glass

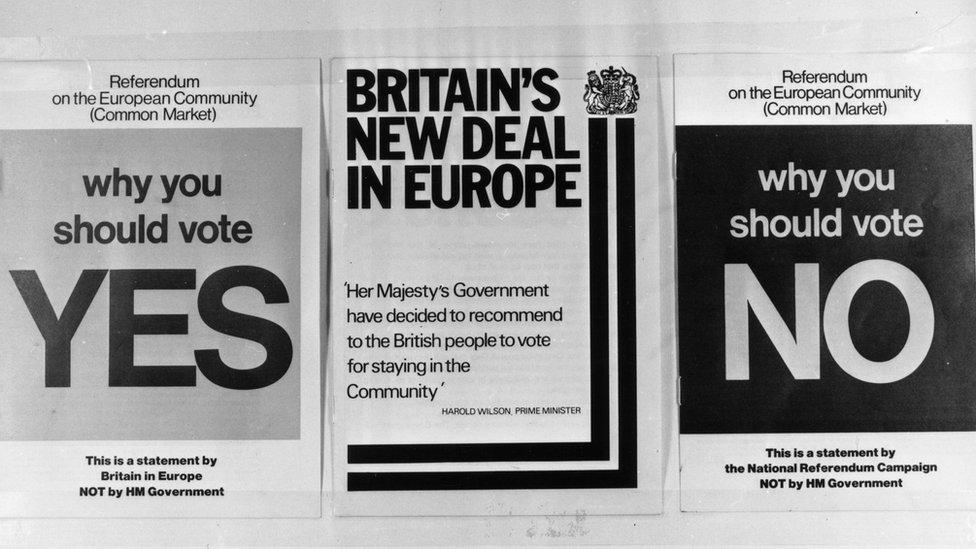

Welcome to the 1975 European referendum - a mirror image of the one being fought today. Today the Conservative government is deeply divided over the big question. In 1975, it was the Labour government. Prime Minister Harold Wilson had come back from Brussels with what he claimed was a better deal for Britain (sound familiar?) and was leading the In campaign.

But Labour's left, led by Tony Benn (and including a then-unknown Jeremy Corbyn), hated the Common Market, seeing it as a "capitalist club" that would erode British democracy and destroy jobs.

The Conservatives - including their new leader Margaret Thatcher - were, almost to a man and woman, enthusiastic cheerleaders for staying in "Europe" on free trade grounds, after taking us into it two years earlier. Like now, big business backed Britain's membership - but so did the tabloid press, with The Sun famously declaring in an editorial "we are all Europeans now".

So who was right?

Running our own affairs

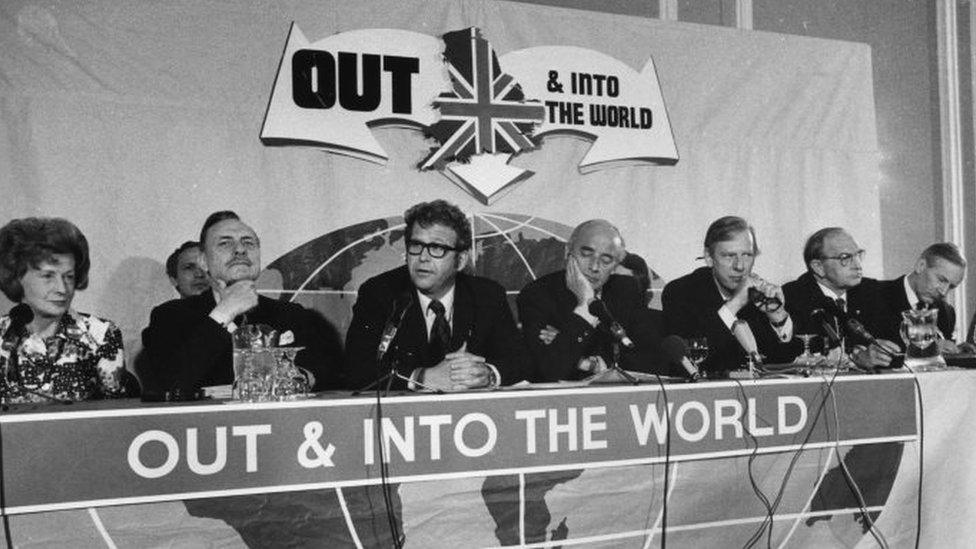

Labour left-wingers shared a platform with Tory right winger Enoch Powell (second left)

A common complaint from those who voted to remain in the EEC in 1975 is that they were hoodwinked - they thought they were voting for a trading arrangement but ended up with a bossy "superstate".

This is not entirely true. Sovereignty - the ability to run our own affairs - was very much an issue in the 1975 referendum.

Enoch Powell, the maverick right wing Tory who had just become an Ulster Unionist MP, and left wing Labour cabinet minister Tony Benn - the loudest voices in the Out campaign - talked endlessly about it.

In its leaflet to voters, the Out campaign warned that the Common Market "sets out by stages to merge Britain with France, Germany, Italy and other countries into a single nation," in which Britain would be a "mere province".

The In campaign openly acknowledged that being a member of the EEC involved "pooling" sovereignty with the eight other nations who were members at the time.

But it said Britain could not go it alone in the modern world and it assured voters that British traditions and way of life were not under threat.

The In campaign also stressed that all the big decisions in Europe would be subject to a prime ministerial veto - something that no longer holds true 41 years later - and that there was no need for Community-wide laws apart from for a "few commercial and industrial purposes". Today's Leave campaigners would take issue with that "few".

Enoch Powell was asked to explain why the British people had ignored his warnings about giving up the power to determine laws, as it became clear that his side had lost.

"It is a thing so incredible to them that I am not inclined to blame them overmuch," he told the BBC.

The price of butter

How the EU affects everyday lives.

With inflation running at 24% (CPI inflation is currently 0.3%), rising food prices were a huge issue for voters in 1975. Some blamed the recent introduction of decimal coins. Others blamed the parlous state of British industry.

The Out campaign blamed the Common Market, which through the Common Agricultural Policy, forced Britain to buy food from other member states and, to give one much quoted example, banned the import of cheap butter from New Zealand.

"The price of butter has to be almost doubled by 1978 if we stay in," warned the Out campaign in its leaflet. In fact, the price of butter quadrupled by 1978, although debate continued to rage about whether the Common Market was entirely to blame for that.

Food mountains

Shoppers faced rapidly rising food prices

The In campaign raised the spectre of food security in 1975, warning that "Britain as a country which cannot feed itself, will be safer in the Community which is almost self-sufficient in food. Otherwise we may find ourselves standing at the end of a world food queue".

In fact, there were huge surpluses of food being sold off at knockdown prices by the EEC itself. Subsidies to farmers had produced "butter mountains," "beef mountains" and "wine lakes". The surplus food was, as the Out campaign pointed out, being destroyed or sold off to Russia "at prices well below what the housewife in the Common Market has to pay".

We don't hear much about European "butter mountains" these days. The EU is taking action to end the "dumping" of cheap food on African nations, where it has damaged local farmers, although everyone - including the Remain camp - still thinks the Common Agricultural Policy is in need of further reform.

The UK is, however, heavily dependent on other EU member states for food. UK food production is below 60% of consumption and particularly reliant on imports for fruit and many vegetables, according to the National Farmers Union, which backs a Remain vote. UKIP points to a 2008 Defra report, external which suggests Britain could, at a pinch, become self-sufficient if had to.

Jobs and trade

Britain was widely assumed to be in terminal decline

Out campaigner Tony Benn claimed Britain's membership of the EEC had cost 500,000 British jobs in just two years. He blamed rising unemployment on the growing trade deficit between Britain and the rest of the EEC. We were importing far more stuff from European countries than we were exporting to them.

(Britain has continued to run a trade deficit with the rest of the EU, and it hit a record high this year, thanks in part to a stronger pound.)

The In campaign said Mr Benn had effectively plucked the jobs figure out of thin air and the real cause of rising unemployment was the global slump and rampant inflation, which was well above levels in the rest of Europe.

They warned that leaving the EU would be potentially "disastrous" for British industry as it would block access to a market of what was then 250 million people.

In an echo of the arguments being made today, the 1975 In campaign said that even if Britain was able to negotiate a free trade deal with the EEC it "would have to accept many Community rules" without having any say in how they are made.

Lurking behind this debate was the growing feeling that Britain - crippled by strikes, power cuts and inflation - was just about finished as a country.

"Since the national decline of Britain became fully apparent after the war there has never been a rational alternative to a European base for the redevelopment of Britain," the pro-EU Times argued in an editorial.

Out campaigners argued the only way to save Britain was to get out of the EU, but the British public in 1975 were not convinced.

The Commonwealth

The Queen continues to be head of the Commonwealth

Britain had only just given up its empire in 1975, so there was much anxiety about what would happen to the country's links with its former colonies.

Britain had to cut most of its trade links with the Commonwealth nations and replace them with trade deals with the EEC. This prompted the Out campaign to claim that Britain would effectively cease to be a member of the Commonwealth.

The In campaign said the leaders of the Commonwealth nations all wanted Britain to remain in the EU and assured voters that the Queen would "continue to be head of the Commonwealth".

This issue has resurfaced in the current campaign, with Leave campaigners saying Britain would be able to strike its own trade deals with Commonwealth nations, although some economists have suggested that may result in something close to the status quo, as the EU already has deals with the majority of former British colonies.

What no one saw coming

The fall of the Berlin Wall brought former Communist bloc states into the EU

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent admittance of former Communist bloc states, such as Poland and the Czech Republic, into the European Union would have seemed an extremely far-fetched proposition in 1975. The Cold War and the Soviet Union were seemingly immovable facts of life back then.

The In campaign even declared in its leaflet that "some want a Communist Britain - part of the Soviet bloc". The Common Market was sold to voters as a bulwark against Soviet aggression, in much the same way as today's Remain campaign claims Vladimir Putin would celebrate a British Leave vote.

Immigration was not an issue

The other dog that didn't bark in 1975 was immigration. It was barely mentioned at all during the campaign. This was due, in part, to the fact that there were still limits on workers from other member states. Full EU "free movement" did not kick in until after the 1992 Maastricht Treaty was signed. But the idea that people would want to come to a depressed, economically stagnant Britain in large numbers would have seemed fanciful at best in 1975. The growth of emigration was more of a concern.

So what lessons can we draw from 1975?

Perhaps the biggest lesson is that although some of the things the Out campaign were warning about, particularly on sovereignty, have come to pass - and the In campaign will claim Britain's membership has delivered the peace, stability and prosperity their kipper-tied forebears had promised - it is best to take confident predictions about what might happen in the future, from either side, with a large pinch of salt.