View from Parliament: What happens next?

- Published

David Cameron is going, and the key decisions on Brexit will be taken by a new leader

What happens next? Everything at once.

We definitely have a Conservative leadership battle; we may well have a Labour one, as well. (The ever-helpful House of Commons Library has produced a very handy briefing on the rules., external) The Scottish first minister has said a second independence referendum is now "highly likely".

And against the background of all that political turmoil, Parliament will have to start the detailed work of interpreting the instruction handed to them by the electorate.

In one sense, David Cameron's decision to go, as soon as a successor can be chosen, does allow a pause for breath; it will be the new prime minister who takes the decision about when to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and start the clock running on a two year negotiation process.

They will name the negotiation team that heads off to rewrite the UK's relationship with the EU, and they will decide the objectives and strategy for that negotiation.

So the key decisions will not be taken until Mr Cameron has departed - but that also guarantees that the leadership election will be dominated by competing visions of the future relationship between Britain, the EU and the wider world.

This will feed into an extensive parliamentary debate, which will doubtless happen very soon.

Single market?

My guess there will be a full dress Commons debate, probably over several days, to explore the issues and start hammering out the UK's negotiating aims, and the major leadership candidates will, in effect be auditioning.

So, indeed, may be a whole series of aspiring ministers and would-be negotiators. The select committees will weigh in, and further down the road there may be debates on specific aspects of Brexit.

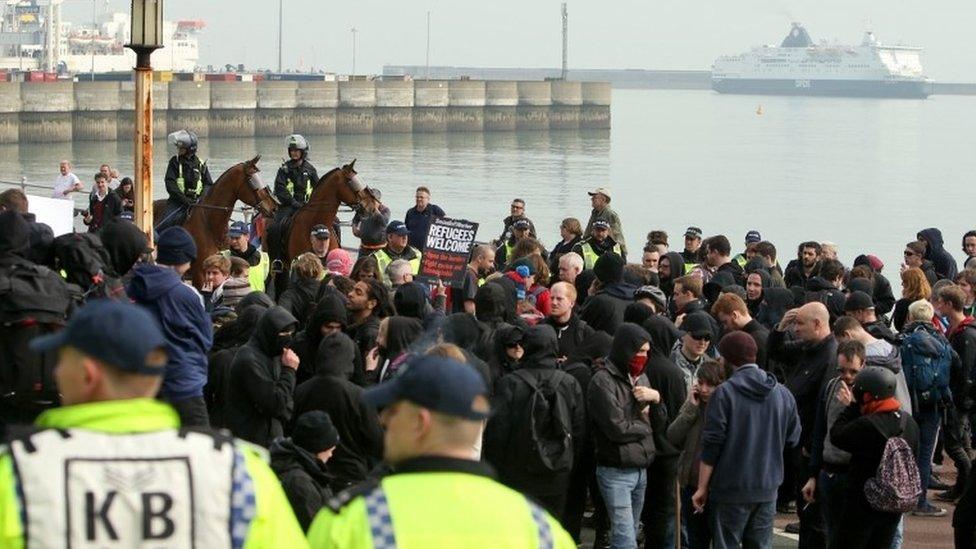

There have been protests in Dover over immigration issues - will Brexit mean emergency border controls?

Which aspects of 40 years of accumulated EU law should Britain keep? Will the writ of the European Arrest Warrant still run? Will there need to be emergency immigration controls?

And then there's the key point (as made by Labour's Stephen Kinnock) that a majority of MPs would probably like to keep the UK in the single market and could well insist on making that a part of the negotiating brief.

One source of ideas and analysis on these issues is the Fresh Start Project, external, a think tank founded a few years ago by key pro-Brexit campaigner Andrea Leadsom, to look in detail about how a reset relationship with the EU might work.

Ideologically pure

The classic Whitehall lesson, that the most influential document is the first one on the table, may well apply here - Fresh Start's reports and thinking may become the basic work against which later policy analysis is judged.

And when the negotiations do start, they will attract a great deal of parliamentary attention. The talks on a European Constitution, a few years back, included not just an official delegation of British ministers, but also observers from the Commons - one Gisela Stuart among them.

Which brings me to another point. It's already clear that the next administration will be a Brexit government, almost certainly led by an ideologically pure Brexiteer, and that whoever the Conservative Party chooses as the new prime minister will have to bring in or promote more prominent Brexiteers.

Many predict more prominent roles for Brexiteers now - not just Boris Johnson but Labour's Gisela Stuart (c) and Tory Andrea Leadsom (r)

Rocket boosters have just been attached to the careers of middle-ranking ministers who campaigned on the Leave side, like Andrea Leadsom (a Tory MP I asked about the future texted me three words…Leadsom, Leadsom, Leadsom!) or Dominic Raab.

And the second coming of some pro-Brexit ex-ministers like Liam Fox is probably imminent.

Some of the most prominent Remain ministers will find themselves on the backbenches, if only to make room for the victors. In one sense, the Brexit vote probably makes it easier to reconstruct Tory unity.

A narrow Remain vote would have meant a prolonged insurgency; with Brexit almost every Conservative MP will have to climb aboard and adapt to the new reality.

Labour's Brexiteers

But what of the Labour side? Almost all Labour MPs campaigned for Remain, and some were cranking up to revenge themselves on party colleagues who they thought had allied themselves with Nigel Farage.

Now the question is whether Jeremy Corbyn (or a successor) has to elevate Gisela Stuart, or John Mann, or Frank Field to Labour's top table.

Some Labour strategists, eyeing the chasm between their pro-remain, metropolitan liberal wing, and their pro-Brexit vote in traditional territory outside London, believe there's an urgent need to re-connect before UKIP or some other competitor moves in, and they suffer a Scottish-style collapse in their former heartlands.

Could a new government seek to stay in the EU?

Again, this is a battle that may be fought out in debates on the floor of the Commons. For my money, a key figure to watch is the Bassetlaw MP, John Mann, who has a sharp populist edge, and who has raged at the failure of successive Labour leaders to connect with his electorate.

It's a heady cocktail - the debate about to start in Parliament is a combination of the mechanics of resetting the UK's relationship with the EU, the ambitions of a variety of Conservative and Labour folk for the leadership of their parties - and the urgent need across parties to reconnect with voters who feel politics has left them behind.

It may go on till 2019, which makes it quite possible that a new prime minister, seeking a new mandate, could hold a general election before Brexit is accomplished.

But that raises the very interesting question of whether the mandate of a new House of Commons would trump that of the referendum. Suppose the country chose a new government prepared to compromise on the key Brexit-motivating issue of immigration and free movement?

Or suppose it was formed by a party which was less keen on Brexit, perhaps because they didn't like the terms of the deal on offer? Could a new government seek a different deal, or even to Remain, after all.

Suppose this week's vote turns out to be less final than it seems now? What then?

Nobody knows.

- Published17 June 2016

- Published17 June 2016