EU referendum: does Parliament press the button?

- Published

- comments

Who presses the button? When is the divorce petition filed?

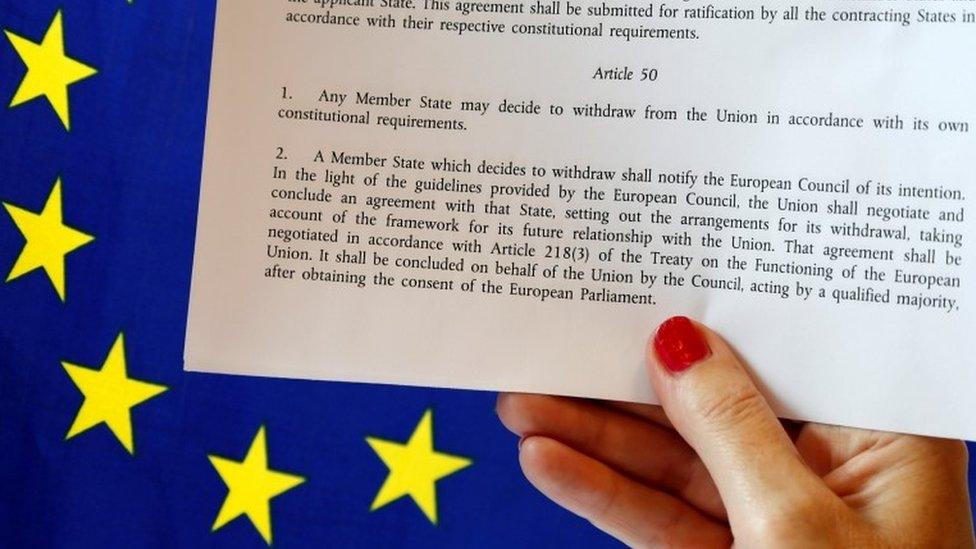

Whatever the metaphor, the decision to trigger Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union, the one which provides for member states to withdraw, has emerged as the critical next step.

And a number of constitutional scholars are now questioning whether the prime minister is entitled to take that step, without the explicit consent of Parliament.

There's a very technical argument about whether the "prerogative powers" normally exercised by a prime minister can be used for a decision which would change the law* - but there's some very hard politics lurking behind it.

No room for a rethink

The key point is that once triggered, Article 50 forecloses the possibility of any rethink of the "Leave" decision. That's why many (although far from all) Brexiteers want it triggered as soon as possible, to prevent any backsliding.

On the other hand, those who nurse hopes of a rethink, maybe a second referendum, or a general election mandate to reverse the referendum verdict, want the Article 50 letter to be postponed for as long as possible for precisely the same reason.

David Cameron's successor will have to deal with the implications of Article 50 and the role of Parliament

The point is that after the trigger point, a formal letter from the British government to the European Council, notifying them of intent to withdraw, there is no provision for the departing member state to change its mind; that would require the unanimous consent of the other EU member states, and they might either refuse, or demand a price - Spain, to give an example off the top of my head, might want Gibraltar back.

If the next PM simply sends the letter as an exercise in prerogative power they could face a legal challenge on the basis that Article 50 requires a withdrawing state to act "in accordance with its own constitutional requirements".

On the other hand, if the decision was laid before the Commons and the Lords, there is at least the potential for an upset. A prime minister's power to commit British troops to military action is an example of a prerogative power which has, since the precedent set by Tony Blair over Iraq, become subject to the approval of MPs, and that led to David Cameron's defeat over Syria.

His successor might be forced to concede the point over Article 50. Alternatively, there may be some attempt to force the issue, perhaps with a motion to the Commons demanding that the House be asked to consent.

But it would be a very courageous - in the "Yes Minister" sense of the term - for any MP to go down this road

* The legal arguments are rehearsed here, on the excellent UK Constitutional Law blog, external

- Published17 June 2016

- Published17 June 2016