The Nigel Farage story

- Published

Nigel Farage has led his party, on and off, for 10 years

Nigel Farage's slogan during his 20-year campaign to take the UK out of the European Union was "I want my country back".

Now the UKIP leader has achieved his ultimate political ambition, seemingly against all the odds. And he has turned that epithet on himself - telling reporters that he "wants his life back" and is now standing down.

The face of Euroscepticism in the UK for getting on for two decades, Mr Farage helped turn UKIP from a fringe force to the third biggest party in UK politics in terms of votes at the 2015 general election, and he helped persuade more than 17 million people to vote to leave the EU.

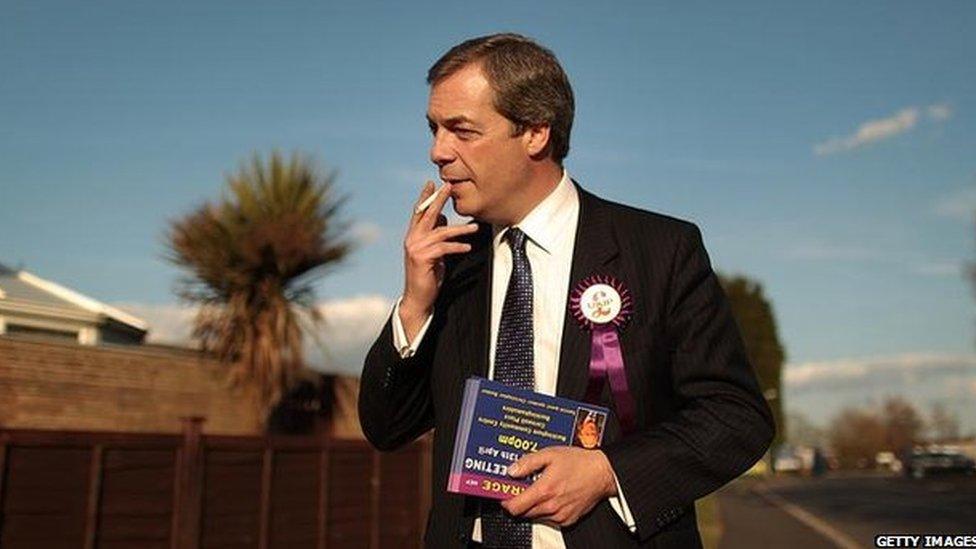

Few politicians have been more closely identified with the party they lead. Much of that success has been a product of Mr Farage's straight talking, everyman image, a picture editor's dream when snapped grinning with pint or cigarette (sometimes both) in hand.

His "man in the pub" image and disdain for political correctness left him free to attack rivals for being mechanical and overly on-message.

This inspired affection and respect among those who agreed with him on core messages about cutting immigration and leaving the EU.

True to his image as an outspoken saloon bar philosopher, he got into plenty of fights.

Nigel Farage: "Part of me is happier than I have felt for many, many years"

During the general election campaign, it was over TV debate comments he made about migrants using the NHS for expensive HIV treatment. They drew an angry rebuke from Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood, who told him: "You ought to be ashamed of yourself."

But despite widespread condemnation from opponents, reports quoted UKIP insiders saying the comments - dubbed "shock and awful" - were part of a carefully planned move to appeal to the party's base. One senior aide was quoted as saying his remarks would be welcomed by "millions and millions" of working-class voters.

Nigel Farage: “We’ve got to put our own people first”

So how did a stockbroker's son become a mouthpiece for the disaffected working class?

Nigel Paul Farage was born on 3 April 1964 in Kent. His alcoholic father, Guy Oscar Justus Farage, walked out on the family when Nigel was five.

Yet this seemed to do little to damage the youngster's conventional upper-middle-class upbringing. Nigel attended fee-paying Dulwich College, where he developed a love of cricket, rugby and political debate.

He decided at the age of 18 not to go to university, entering the City instead.

Nigel Farage style of campaigning marked him out from other politicians

With his gregarious, laddish ways he proved popular among clients and fellow traders on the metals exchange. Mr Farage, who started work just before the "big bang" in the City, earned a more-than-comfortable living, but had another calling - politics.

Farage factfile

Age: 52

Family: Married with two daughters to Kirsten Mehr. Two grown-up sons with ex-wife

Education: Did not attend university after leaving fee-paying Dulwich College at 18

Career: City commodities trader from 1982, starting at London Metals Exchange

Political timeline:

1992 - Left Conservatives in protest at signing of Maastricht Treaty

1993 - Founder member of UKIP

1999 - Elected to European Parliament, representing South East England

2006 - Elected UKIP leader

2009 - Stood down to challenge Speaker John Bercow in 2010 general election

2010 - Despite failing to become an MP, won second leadership contest

2014 - Led UKIP to largest share of vote in European election

2015 - Fought Kent seat of South Thanet in general election

2016 - Helps Leave campaign to win EU referendum

2016 - Announces standing down as UKIP leader

Pastimes: Shore fishing, WW1 battlefield tours, Dad's Army, cricket, red wine

Mr Farage joined the Conservatives but became disillusioned with the way the party was going under John Major. Like many on the Eurosceptic wing, he was furious when the prime minister signed the Maastricht Treaty, stipulating an "ever-closer union" between European nations.

Mr Farage decided to break away, becoming one of the founder members of the UK Independence Party, at that time known as the Anti-Federalist League.

In his early 20s, he had the first of several brushes with death, when he was run over by a car in Orpington, Kent, after a night in the pub. He sustained severe injuries and doctors feared he would lose a leg. Grainne Hayes, his nurse, became his first wife.

He had two sons with Ms Hayes, both now grown up, and two daughters with his current wife, Kirsten Mehr, a German national he married in 1999.

Farage in quotes

"At first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win," speaking - after Mahatma Gandhi - in April 2015 about UKIP's election chances

"It took me six hours and 15 minutes to get here... because of open-door immigration and the fact that the M4 is not as navigable as it used to be," his excuse for being late for a meeting in Wales in December 2014

"I want the EU to end but I want it to end democratically. If it doesn't end democratically I'm afraid it will end very unpleasantly," during a Euro election debate with Nick Clegg in April 2014

"I don't want to be rude... Who are you? I'd never heard of you, nobody in Europe had ever heard of you," his greeting to President of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, in February 2010

"As... his personal make-up artist straightened his chest hair for him, I kid you not, I realised that perhaps he might be a bit lighter weight than expected," - after Question Time with comedian Russell Brand in December 2014

Months after recovering from his road accident, Mr Farage was diagnosed with testicular cancer.

He made a full recovery, but he says the experience changed him, making him even more determined to make the most of life.

The young Farage might have had energy and enthusiasm to spare - but his early electoral forays with UKIP proved frustrating.

At the 1997 general election, it was overshadowed by the Referendum Party, backed by multimillionaire businessman Sir James Goldsmith.

Fed-up with what they describe as a pro-European conspiracy among the major parties, the UK Independence Party believe that their time has come

But as the Referendum Party faded, UKIP started to take up some of its hardcore anti-EU support.

In 1999, it saw its first electoral breakthrough - thanks to the introduction of proportional representation for European elections, which made it easier for smaller parties to gain seats.

Mr Farage was one of three UKIP members voted in to the European Parliament, representing South East England.

The decision to take up seats in Brussels sparked one of many splits in the UKIP ranks - they were proving to be a rancorous bunch.

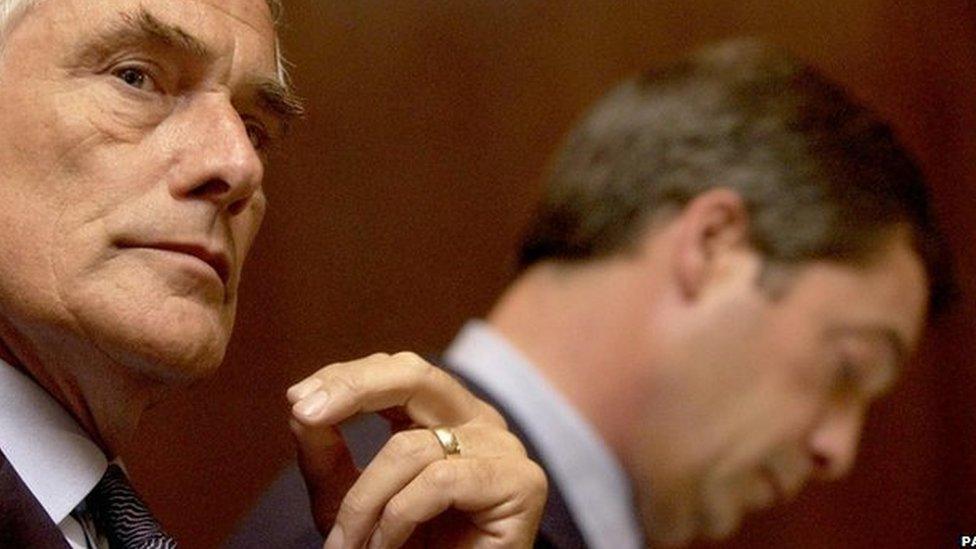

Mr Farage scored a publicity coup by recruiting former TV presenter and ex-Labour MP Robert Kilroy-Silk to be a candidate in the 2004 European elections, but the plan backfired when Mr Kilroy-Silk attempted to take over the party.

Nigel Farage's fight with Robert Kilroy-Silk marked a low point for the party

It was a turbulent time for UKIP but in that year's elections it had increased its number of MEPs to 12.

In 2006, Mr Farage was elected leader, replacing the less flamboyant Roger Knapman.

He was already a fierce critic of Conservative leader David Cameron, who earlier that year had described UKIP members as "fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists".

Mr Farage told the press that "nine out of 10" Tories agreed with his party's views on Europe.

Asked if UKIP was declaring war on the Conservatives, he said: "It is a war between UKIP and the entire political establishment."

The world on Farage

"We Tories look at him, with his pint and cigar and sense of humour, and instinctively recognise someone fundamentally indistinguishable from us," London Mayor Boris Johnson in 2013

"This man is not a cartoon character, he isn't Del Boy or Arthur Daley, he's a pound shop Enoch Powell and we're watching him," Russell Brand on Question Time in 2014

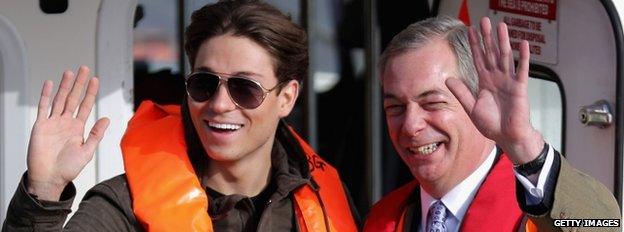

"He's a really, really reem guy... It means cool, wicked, sick." Reality TV star Joey Essex during the 2015 election campaign

"You are either serious or a kind of Victor Meldrew on stilts. Which one are you?" Nick Clegg in 2015

"He's very outspoken - even the people who don't share his message think that he's a great speaker and fun to listen to." Timo Soini, of the eurosceptic True Finns party

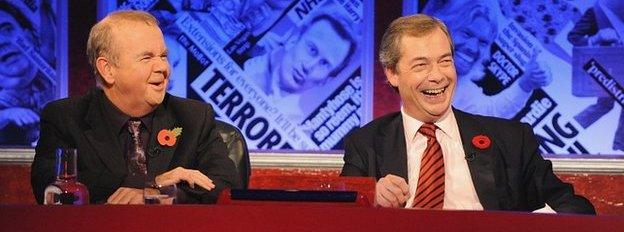

At the 2009 European elections, with Mr Farage becoming a regular fixture on TV discussion programmes, UKIP got more votes than Labour and the Lib Dems, and increased its number of MEPs to 13.

But the party knew it could do little to bring about its goal of getting Britain out of the EU from Brussels and Strasbourg - and it had always performed poorly in UK domestic elections.

In an effort to change this, Mr Farage resigned as leader in 2009 to contest the Buckingham seat held by House of Commons Speaker John Bercow.

He gained widespread publicity in March 2010 - two months before the election - when he launched an attack in the European Parliament on the president of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, accusing him of having "the charisma of a damp rag" and "the appearance of a low-grade bank clerk".

It raised Mr Farage's profile, going viral on the internet, but made little difference to his Westminster ambitions. He came third, behind Mr Bercow and an independent candidate.

Mr Farage's chosen successor as leader, Lord Pearson of Rannoch, was not suited to the cut-and-thrust of modern political debate and presentation, and UKIP polled just 3.1% nationally.

But there was a far greater personal disaster. On the day of the election a plane carrying Mr Farage crashed after its UKIP-promoting banner became entangled in the tail fin.

He was dragged from the wreckage with serious injuries.

The plane crash on polling day in 2010 left the UKIP leader with long-term injuries

After recovering in hospital, he told the London Evening Standard the experience had changed him: "I think it's made me more 'me' than I was before, to be honest. Even more fatalistic.

"Even more convinced it's not a dress rehearsal. Even more driven than I was before. And I am driven."

Mr Farage decided he wanted to become leader again and was easily voted back after Lord Pearson resigned.

His party's fortunes rose again as Europe, and particularly migration to the UK from EU countries, continued as a fast-growing political issue with the increased numbers following enlargement to include former communist states from Eastern Europe in 2004.

Mr Farage resigned in 2015 but this time says there is no chance of him coming back

Mr Farage increased UKIP's focus on the immigration impact of EU membership, referring to Britain's "open door" causing congestion on the M4, a Romanian crime wave in London and a shortage of housing, healthcare, school places and jobs for young people.

It led to repeated accusations of racism, described by Mr Farage as "grossly unfair". His strategy had long been to distance the party from the far right - its constitution bans former BNP members from joining.

Rather, he aimed to be seen as tribune for the disenfranchised, not just the older, comfortably off middle classes alienated by rapid social change caused by mass immigration, but working-class voters left behind in the hunt for jobs and seemingly ignored by the increasingly professionalised "political class".

Mr Farage's focus on immigration caused controversy but helped changed the outcome of the EU referendum

Despite facing vocal protests, which in one high-profile case led to him having to take refuge from what he called "supporters of Scottish nationalism" in an Edinburgh pub in 2013 and on another occasion saw him being chased by "diversity" activists in London in 2015, his efforts saw UKIP's influence increase.

After winning more than 140 English council seats at the 2013 local election - averaging 25% of the vote in the wards where it was standing - it gained 161 last year.

More significantly, the party won the UK's European election outright, gaining 27.5% of the vote. Its momentum then built when Tory defector Douglas Carswell forced a by-election to secure UKIP's first parliamentary seat, with colleague Mark Reckless following suit shortly afterwards.

While polls charted a steady decline in UKIP support through 2015, commentators noted an unusual lack of energy from its leader and questioned whether he was fit for the fight.

Mr Farage has said he will remain as an MEP in Brussels to ensure there is no "backsliding" on Brexit

It prompted Mr Farage to reveal he'd been in "a great deal of pain" at the start of the campaign, having neglected a chronic back condition caused by his plane crash. Despite physiotherapy helping his energy levels return, he never made the impact some thought he might.

Comments ahead of polling day that UKIP was "about a lot more than me", and that he was "a complete convert" to proportional representation, hinted that he believed the game was up.

Despite gaining 13% of the vote at the general election, with nearly four million people casting a ballot for the party, they only managed to return one MP, Douglas Carswell, with Mark Reckless losing his seat.

Mr Farage failed in his bid to win South Thanet, losing out by 3,000 votes to the Conservatives.

Having said during the campaign that he would be "for the chop" if he didn't win, he duly announced his resignation as party leader on the morning after polling day.

However, he left the door open for a possible return by saying he might stand in the leadership contest after he had had the summer off.

Big figure

Then he surprised some in the party by announcing that he had changed his mind after being "persuaded" by "overwhelming" evidence from UKIP members that they wanted him to remain leader - insisting that he wanted to stick around for the referendum battle ahead.

That decision was vindicated, with Mr Farage playing a key role in the bruising campaign that followed despite being shunned by many Conservatives on the same side of the argument.

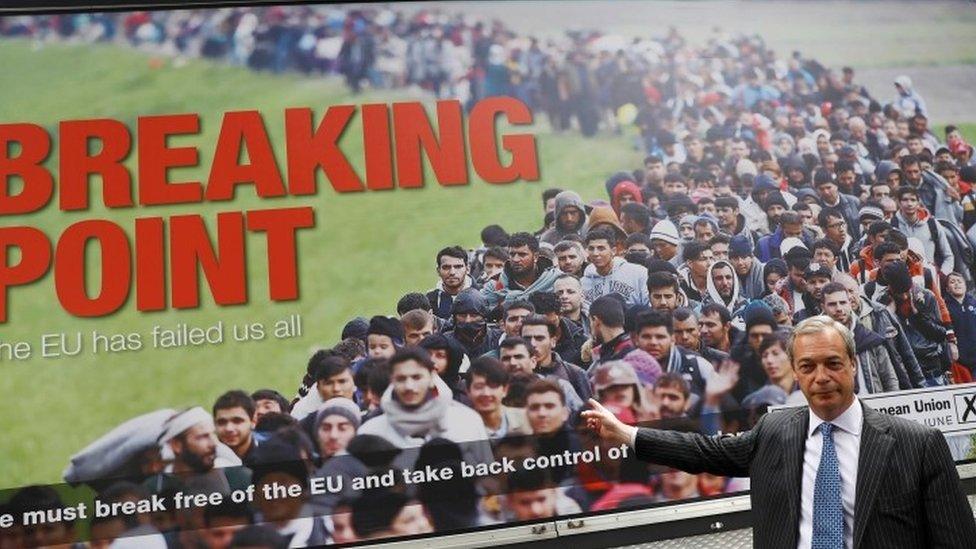

His focus on immigration was not to everyone's liking - a UKIP poster featuring a line of refugees with the words 'Breaking Point' caused widespread anger - but the fact that it became a defining issue in the campaign was in no small measure down to him.

The UKIP leader was the first to celebrate victory with an emotional speech in the early hours of the morning - before the sensational result had been declared.

Now after his latest resignation Mr Farage, who has fallen out with a number of colleagues over the years including Godfrey Bloom, Suzanne Evans and Douglas Carswell, has insisted he will not be coming back and has promised to give whoever succeeds him his full support.

However, he will remain a big figure in the party and has pledged during his remaining time in Brussels to follow the UK's Brexit's negotiations "like a hawk" to ensure there is in his words "no backsliding or weakness".

And he warned the other parties to "watch this space" at the General Election in 2020 if they failed to fully implement Brexit.

- Published8 May 2015