The new divide: Hard or soft Brexit?

- Published

How might Brexit change the existing landscape of British politics, and how might the main political parties position themselves?

With the thunderous explosions from the referendum vote still ringing in our ears, new battle lines in British politics are being drawn up.

Old alliances may crumble as new ones are forged.

This is not about the Westminster leadership elections. They are part of it, but only a part. Think of the players you see every day on the TV as the tip of the iceberg. The iceberg which sank the Titanic only did so because of the mass behind it, lurking underwater.

New movements are afoot, for the moment subterranean. Earnest meetings are being held in homes and offices and universities.

They may wither away. They may become a mass movement that re-define politics.

Reality Check: Can UK trigger Article 50 without asking Parliament?

Legal action over MPs' role in Brexit

Politicians have been quick to declare that "we are all Brexiters now". Most political observers have judged this the sane position.

Maybe that is because they - we - are hard-headed realists who can see the political impossibility of betraying the 52%.

Maybe it's because we can't think outside a box constructed of party political logic, and haven't quite caught up with the depth of the new divides.

But it is certainly true we are in a different world now.

"Leave" and "Remain" are not so much old hat as the new tribes - the way we see ourselves and our country.

But the actual crux of the argument that will dominate the next few months, and probably years, is subtly different.

It is between hard and soft Brexit.

Theresa May has said the UK wants more than a "Brexit PM"

There will be quite literally thousands of details to negotiate, which will occupy civil servants, who'll have to be hastily recruited, for years. But the critical heart of the debate will between the worth of the single market , external and the need to curb immigration.

It's not a new thought to point out that the battle over the Corn Laws which tore the Conservative Party asunder in the 19th Century was about free trade versus nationalism. That is very bad for the Conservative Party.

Or perhaps it was about class interest, the emerging middle class against the old aristocracy - this time played out by a split between the old and left behind working class, and the middle class basking in the joys of globalisation. That is very bad for the Labour Party.

Both are worth remembering if we are thinking about realignment.

The "hard Brexiters" are those want to act quickly and be gone. They want to curb European migration as quickly as possible, using a points system. They don't much value being part of the single market, and point out that just about every nation in the world has "access" to it, without being a member.

You can call this the "Canada lite" model if you like.

"Soft Brexiters" want to take their time, and retain as close a relationship with the rest of the European Union as possible. They want access to the single market, and some sort of minor concession on free movement.

Perhaps, they muse, the EU would give us an emergency brake and annual quotas on both sides. Their priority is to avoid trade tariffs and secure a good deal for services, particularly financial services. That's "Norway plus".

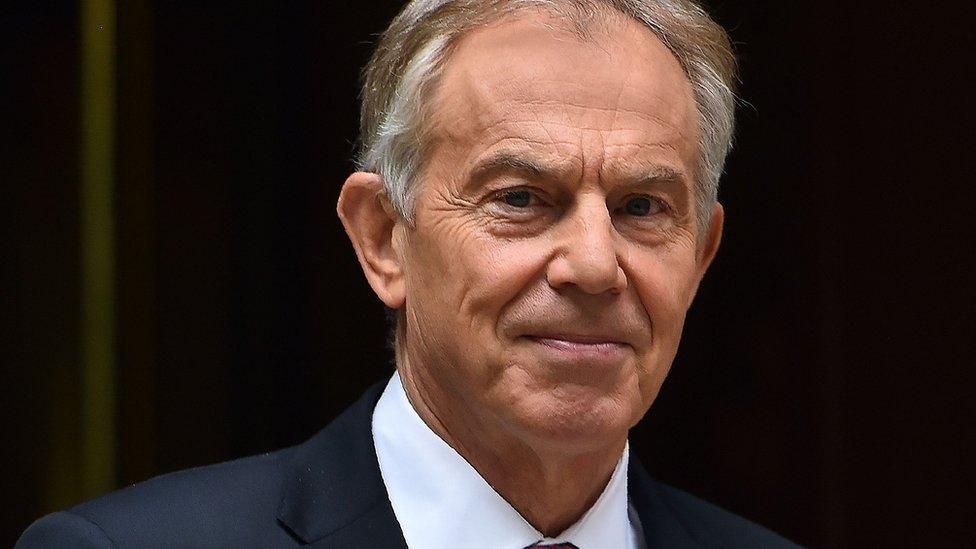

Tony Blair: Country 'should express its views'

This doesn't mean the argument for another bash at it, a second referendum, is over. Those in the 48% who think the result illegitimate for one reason or another will still have their say. Tony Blair told me at the weekend that, "if the will of the people shifts, why shouldn't we recognise that?"

The Liberal Democrats see it as a chance to claw their way back to relevance. They see a big pool of potential voters willing to support them. They will fight the next election on a remain platform.

In the meantime they will harry the Brexiters like a guerrilla army - on the rights of EU citizens living in the UK one day, on the European arrest warrant the next.

Lib Dem leader Tim Farron has been at several anti-Brexit rallies since the referendum result

But as Prof Anand Menon writes in an article for Foreign Affairs, external, "The referendum was, in part, a political protest against a system that no longer adequately represents its people. Overturning the result, therefore, would simply make matters worse."

"One incident at a town hall event sticks in my mind," he recalls. "A couple of colleagues and I were in Newcastle, in the North East, discussing the fact that the vast majority of economists agreed that Brexit would lead to an economic slowdown.

"A 2% drop in the United Kingdom's GDP, I said, would dwarf any savings the country would make from curtailing its contribution to the EU budget. 'That's your bloody GDP,' came the shouted response, 'not ours'."

Those who want a second referendum should reflect on where sidelining those sort of voices could lead.

Nicola Sturgeon has pledged to do all she can to protect Scotland's position in Europe

But I suspect the desire to re-run 23 June 2016 - be it in a referendum or a general election - will fade for a while, return, then hover in the background. It depends on how the negotiations go, how the economy performs.

It will be against the background of a fight between the new battalions.

"Hard Brexiters" are easy to define - about half of the of the Conservative Party, best represented at the moment by Andrea Leadsom, and all those voters who meant what they said when they voted "leave".

"Soft Brexiters" are more complex.

Perhaps the Labour Party - who knows? They are hobbled by the desire of many of their one-time voters for tight controls on immigration. Maybe the woman who currently looks in lead position to become the next Prime Minister, Theresa May?

I suspect the Lib Dems, when it comes down to voting in the commons, will vote for soft Brexit, while holding their noses.

The SNP want to stay. But this push snags on Catalonia. They may hold a second referendum on independence. But in the coming months I suspect they too will join the forces of "soft Brexit".

Jeremy Corbyn lost the support of the parliamentary Labour Party after the referendum

Also important are those getting their act together outside the Palace of Westminster - people in the City, big business, the creative industries.

There's a lot of networking going on. Perhaps not much more, for now, than friends of friends getting together with like-minded friends of friends.

One group wants a campaign to call a general election with a template letter to MPs arguing that a new government should be elected "with a mandate to address the concerns of the millions of people who voted Leave and the millions of people who voted Remain". They aren't absolutely clear what a manifesto would look like, but they are working on one.

There are nascent groupings of the discontented and worried, but no mass movement people can easily sign up to, and no leader. Perhaps neither are wanted or needed.

But it does make me reflect on the failed nature of leadership. There's a confusion between becoming a leader in politics - the need to count the votes and forge alliances - and actual leading.

Politicians as diverse as Tony Benn and Nigel Farage led their cause, not by formally winning a contest, but because of their eloquence and passion.

The mood and the debate outside parliament is important because hard/soft may be the new divide at the heart of the next Conservative government, one faction hitting the accelerator, the other pulling on the handbrake.

We are in the early days of new politics. The emails, private conversations and phone calls taking place right now may define the next battles, and what our relationship with the rest of the world looks like for years to come.

- Published4 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published3 July 2016

- Published3 July 2016

- Published29 June 2016