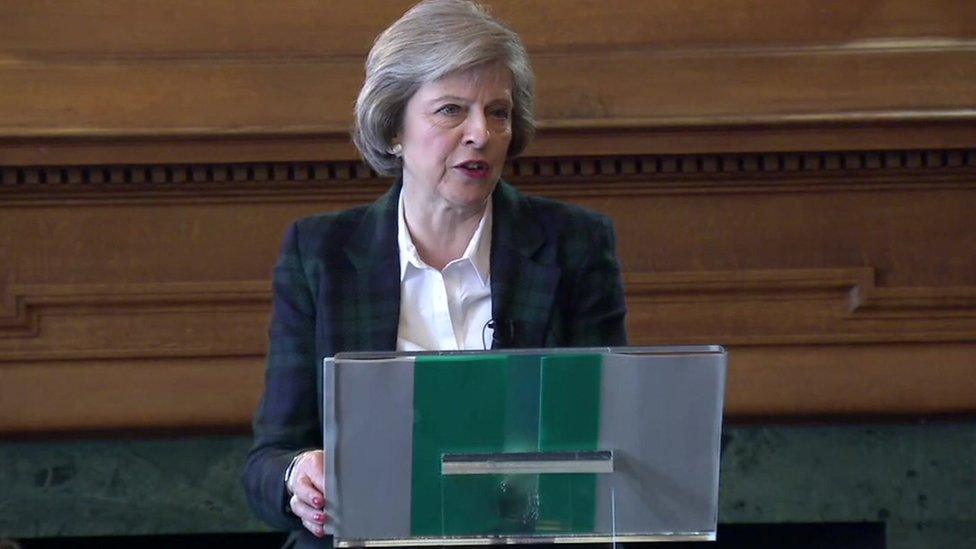

Theresa May: Home Office record-breaker

- Published

Theresa May became home secretary in May 2010

What legacy does Theresa May, the longest-serving home secretary of modern times, leave at the Home Office?

Shortly after Theresa May was appointed Home Secretary in May 2010, she held a small gathering for home affairs journalists in her office.

It was an awkward affair. We stood around Mrs May in a semi-circle, gently questioning her about her intentions at the Home Office, but she was guarded and gave little away.

Two months later, I met the new home secretary again following a speech she'd delivered in London on anti-social behaviour reform. I was tasked with doing an interview.

Again, it was all rather uncomfortable. As the cameraman set up the lights and checked the sound, I tried to make small talk about the upcoming summer holidays, but Mrs May again appeared wary, offering little.

During the interview itself she seemed ill-at-ease, repeating the main messages from her speech in a robotic way, avoiding attempts to steer the discussion in other directions.

It left me with the impression that the former chairman of the Conservative Party, who'd never shadowed home affairs in opposition, was going to struggle in her new role.

The Home Office is an unforgiving department, with counter-terrorism, policing, crime and immigration the key areas of responsibility. Home secretaries don't usually last longer than a couple of years: Mrs May was the sixth holder of the post in six years.

Yet this vicar's daughter with a penchant for stylish footwear confounded my expectations, and those of many others, by remaining in post for longer than any other home secretary in modern times.

She achieved that partly because David Cameron was less inclined to reshuffle ministers than his predecessors; partly because the (mainly) right-wing papers that were so hostile when things went wrong for Labour home secretaries David Blunkett, Charles Clarke and Jacqui Smith were more sympathetic towards Mrs May; and partly because the climate of law-and-order has been more benign, with crime falling and dropping off the agenda as a key issue for voters.

Mrs May's relations with police representatives have often been fraught

Above all, however, Theresa May survived as home secretary because she had a vice-like grip on her department. And as time went on she developed a detailed and deep understanding and knowledge of the brief.

Nick Herbert, policing minister under Mrs May for two years, said she was a "micro-manager" who didn't always make life "easy" for the people working with her.

"Theresa is a fierce manager of her team," he told me in 2014. "She has the ability to command a meeting by sheer force of personality and not to let an issue go."

Lord Gordon Wasserman, a former Home Office civil servant who advised Mrs May on police reform, said she was more dedicated to her job and less interested in the trappings of office than other secretaries of state he's worked with - preferring to eat a sandwich at her desk than have an expensive lunch.

"Someone once said to me, 'there's a lot of work in work' - and she does that," said the Conservative peer, adding that the Maidenhead MP had the advantage of a lack of "baggage" which enabled her to be more ruthless in her decision-making.

Indeed, Mrs May's single-mindedness helped drive through the most far-reaching changes to policing in a generation, with the replacement of police authorities by 41 police and crime commissioners: the way forces are governed will never be the same again.

Theresa May had to contend with the 2011 riots

Organisations that she distrusted - the National Policing Improvement Agency, the Association of Chief Police Officers, the Police Federation - have either been scrapped or neutered. Those which are independent of the police - HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and the Independent Police Complaints Commission - have seen their budgets and influence increase.

Mrs May has been as tough on stop-and-search, deaths in custody and police corruption as a Labour home secretary would have been, perhaps even tougher. She gave no concessions to forces in the first five years of austerity, and pushed on with reforms to police pensions, pay and conditions making her, arguably, the least popular home secretary among rank-and-file officers for decades.

Although relations are less frosty than they were at the time of her electrifying speech to the Police Federation in May 2014, the key challenge for her successor will be to rebuild bridges with the service.

There's an important, and long overdue, decision to be made on possible changes to the way firearms officers are dealt with after police shootings, an issue that's fraught with controversy.

Mrs May is said to have developed a deep understanding of her Home Office brief

The new home secretary will also have to resolve whether to press ahead with plans to bring the police and fire services closer together: in some parts, there's bitter opposition to the idea. And the fresh incumbent is likely to face calls to change employment laws to speed up the recruitment of ethnic minority officers.

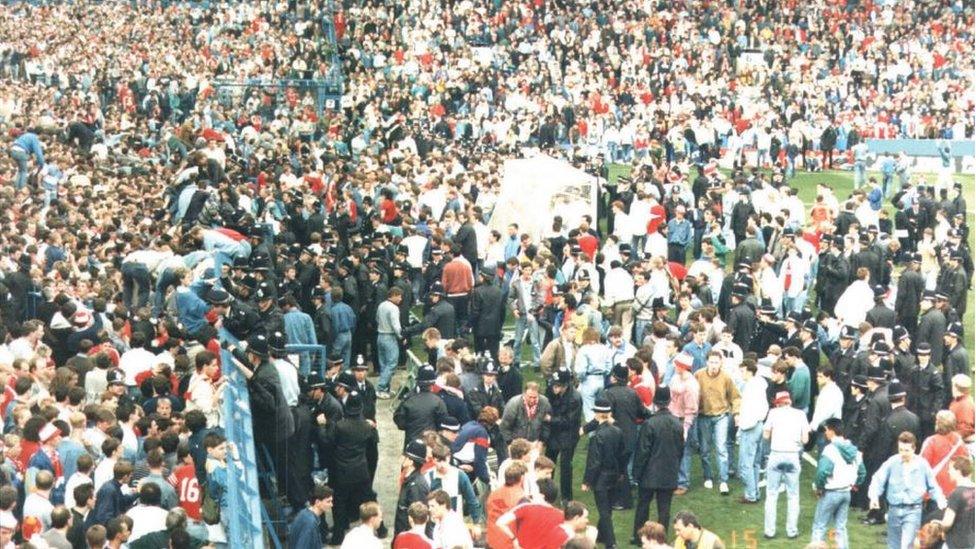

Of course, Theresa May's tenure was about far more than policing. She had to deal with the ever-present threat of terrorism, handle the fallout of the 2011 riots, and chart a way through the minefield of child sexual abuse, following the Jimmy Savile affair.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, set up by Mrs May last year, might turn out to be one of her legacies as home secretary, though her handling of the process to appoint a chairman left much to be desired, after the first two people she selected were forced to resign.

Arguably, the one blot on Theresa May's record has been immigration. Mrs May overhauled the way borders are policed, clamped down on 'bogus' colleges offering courses for foreign students, and tightened the rules for migrants from outside the European Economic Area,

But the key target, to reduce net migration to under 100,000, has still been missed. It's risen from 244,000 when she took office to 333,000 last year, largely as a result of an influx of EU citizens, attracted by the prospect of work.

Immigration was one of the decisive factors in the EU referendum but the government's failure to bring it down to the levels it intended has clearly not damaged Theresa May, whose successor will be hoping to inherit some of her Teflon-like qualities.

- Published25 April 2016

- Published17 May 2016

- Published20 May 2015