10 key moments in David Cameron's time as leader

- Published

David Cameron is stepping down after six years as Britain's prime minister and nearly 11 years as Conservative leader - here are 10 key moments

Hugging huskies in the Arctic

Within weeks of beating better-known rival David Davis to the Conservative leadership in a December 2005 vote of party members, David Cameron was boarding a plane to the Arctic Circle for a fact-finding mission on global warming. It was a dramatic way of announcing himself as a new kind of Conservative - one who cared about the environment and didn't mind enduring freezing temperatures without a hat to prove it (predecessor William Hague had never recovered from being pictured with a baseball cap in the early days of his leadership so headgear was banned on Mr Cameron's Arctic trip).

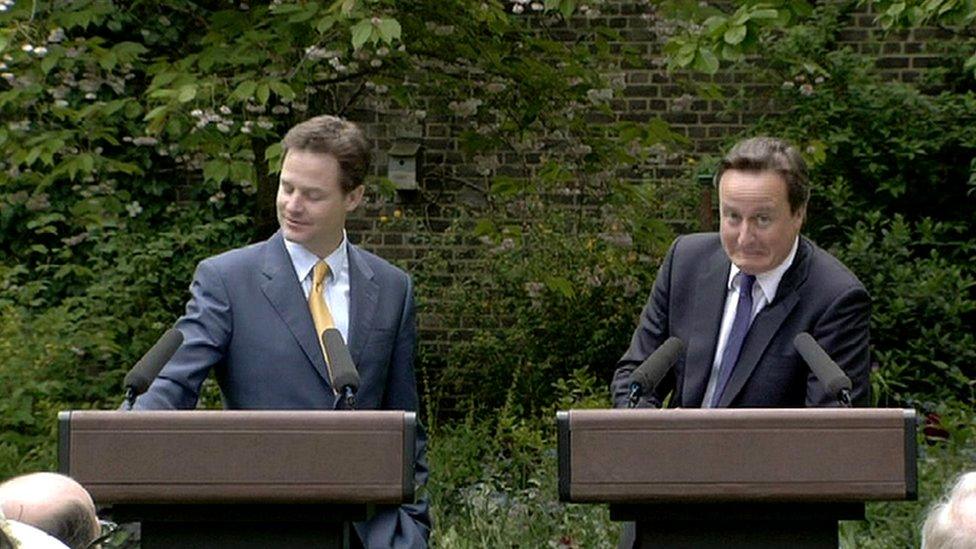

The Nick and Dave show

He never promised us a rose garden. But that's what we got when David Cameron stunned Westminster by making a "big, open and comprehensive" offer to the Liberal Democrats on the morning after a May 2010 general election that nobody won. The bloom-filled Downing Street garden was the venue for the first press conference with Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg after four days of frantic deal-making and intrigue. The body language, as Mr Cameron joshed with Mr Clegg over the insults they had hurled at each other in the past, was good. Britain didn't do coalitions - it had never been tried since World War Two - but this looked like it might just work. Despite the doubters it did last all the way to the 2015 election.

Bloody Sunday statement

David Cameron's ability to look and sound prime ministerial when the occasion demanded it was one of his biggest strengths. It was never more evident than during his Commons statement on the Bloody Sunday inquiry in June 2010, which drew praise from across the political spectrum. He described the findings of the Saville Report into the shooting dead of 13 marchers on 30 January 1972 in Londonderry as "shocking" - an action that was "unjustified" and "unjustifiable", and for which he was "deeply sorry". His statement in 2012 on Hillsborough and his reaction after the April 2016 inquest verdicts earned similar plaudits.

Libyan war

Cameron and Sarkozy were greeted as heroes as they visited a hospital in Libya

Libya was David Cameron's first, and in terms of its long-lasting impact arguably most disastrous, foreign policy intervention. He had pushed a reluctant US President Barack Obama to come to the aid of rebel fighters attempting to topple Colonel Gaddafi and help impose a no-fly zone over Libya. Mr Cameron was greeted as a hero when he visited Libya with then French President Nicolas Sarkozy, in September 2011, after Gaddafi had been ousted. He pledged not to allow Libya to turn into another Iraq, but critics say that is exactly what happened, as it it rapidly descended into violence.

Gay marriage vote

It was one of David Cameron's proudest achievements as prime minister. On 21 May, 2013, MPs voted to allow same-sex couples in England and Wales, who could already hold civil ceremonies, to marry. For Mr Cameron it sent a powerful signal of the kind of tolerant, inclusive country he said he wanted Britain to be - but it cost him dear in terms of lost support from grassroots Conservatives, many of whom could not accept it.

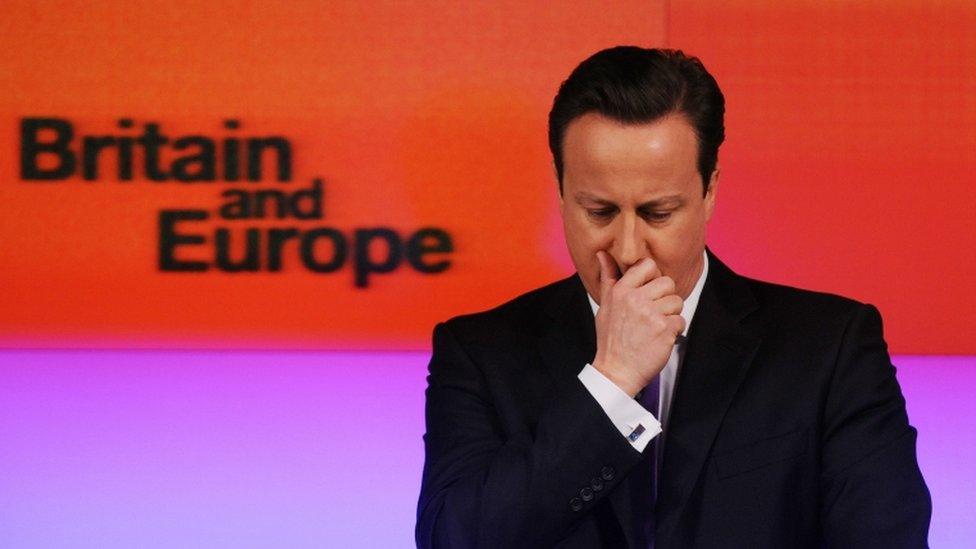

Announcing an EU referendum

After years of rejecting calls from his own MPs for a referendum on Britain's membership of the European Union, Mr Cameron dramatically announced, in a speech at financial wire service Bloomberg in January 2013, that he would hold one if he won the next election, after first renegotiating the UK's membership of the 28-nation bloc. It was the biggest gamble of his political career, made against the backdrop of Eurosceptic rebels in the Tory party demanding a vote and evidence that traditional Conservative voters were heading to the UK Independence Party. As they say in politics, it kicked the can down the road and arguably helped him win the 2015 election. But it was also the vote that ended his career.

Losing Commons vote on Syria

David Cameron: "It is clear to me that the British parliament...does not want to see British military action"

In August 2013, David Cameron became the first prime minister in more than 100 years to lose a Commons vote on military action. It seemed to be a devastating blow to his authority. He had failed to persuade enough MPs, including many on his own side, that Britain should take part in air strikes against the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. "I strongly believe in the need for a tough response to the use of chemical weapons, but I also believe in respecting the will of this House of Commons," he said minutes after the result was announced.

Scottish Referendum panic

Mr Cameron held more referendums than any British prime minister. He easily won the first one in 2011, opposing his deputy PM's bid to change Britain's voting system, but the September 2014 Scottish independence referendum provoked the biggest panic of his first term in office. As polling day approached, he was forced to cancel Prime Minister's Questions and rush north of the border in an effort to save the Union, with an impassioned speech at the HQ of Scottish Widows in Edinburgh, when a poll suggested the Yes campaign would win. He was later forced to issue an apology to the Queen, after he was overheard telling New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg Her Majesty had "purred down the line" when he informed her that Scotland had rejected independence.

Unexpected election victory

In the space of two minutes everything changed. The BBC exit poll predicting the Conservatives would be close to gaining a majority of seats stunned everybody, including, we must assume, David Cameron, who the polls had been suggesting could lose to Labour or have to form another coalition with the Lib Dems. Mr Cameron had been criticised for running a negative, fear-based campaign, but it had succeeded. The pledge to hold an EU referendum if elected also helped gain votes. He formed the first majority Conservative government since 1992 - a personal triumph that would prove to be remarkably short-lived.

Resignation statement

EU vote: David Cameron says the UK "needs fresh leadership"

Mr Cameron had staked everything on his ability to persuade the country to vote to remain in the EU, before realising at a late stage in the campaign that it might not be enough. His tone grew more desperate as he contemplated going down in history as the PM who took Britain out of the EU. Despite insisting he would stay on as PM whatever the result, he announced his departure in an emotional statement in Downing Street within hours of the result becoming clear, with wife Samantha at his side.