Is the left's big new idea a 'right to be lazy'?

- Published

Why are so many on the left now arguing that the state should pay everyone a universal basic income?

Imagine this. You can sit back, relax, turn on the telly, put your feet up. And the government will pay you for it without any of that tedious job-seeking and signing on business.

It sounds like a fantasy. But it's an only slightly exaggerated version of the big idea animating many on the left of British politics, and which has just been adopted by Unite, the country's biggest trade union.

"If you look at the history of the labour movement, the very first thing that the labour movement tried to do was to reduce the working week," says City University politics lecturer Nick Srnicek.

"I think it would be an immense testament to society if we could all be lazy."

The policy behind "the right to be lazy" is an idea called a universal basic income: a flat payment to all adults regardless of circumstances.

Universal basic income

Paid without any need for work

Paid irrespective of any income from other sources

Additional income subject to income tax

UK Green Party advocated similar "Citizen's Income" at 2015 election, external

Swiss voters overwhelmingly rejected a proposal to introduce a guaranteed basic income for all, in June

Unite, Britain's largest trade union, passed a motion endorsing basic income at the Unite 2016 Policy Conference, external on 11 July

It's an idea some trace back to the 18th Century revolutionary Thomas Paine. There's a huge resurgence of interest now in the idea in policy circles and among political big beasts such as former Labour leader Ed Miliband.

"I think the universal basic income is an admirable idea because it thinks big about our society," he says. "It says we want to give people much greater freedom in their lives, much greater freedom to learn, to care for others, to work as well.

"I'd put myself in the category of someone willing to be convinced, but there are obstacles."

The Green Party is already convinced, and the policy has been part of its platform for over 30 years. It is now the subject of multiple pamphlets, think tank debates and even public meetings.

So what does the new-found popularity of this idea say about the intellectual state of the left today?

One answer lies in the response to the changing world of work. Over the past few decades, machines and computers have increasingly replaced "routine jobs" - in factories and banks - and that has increased wage inequality.

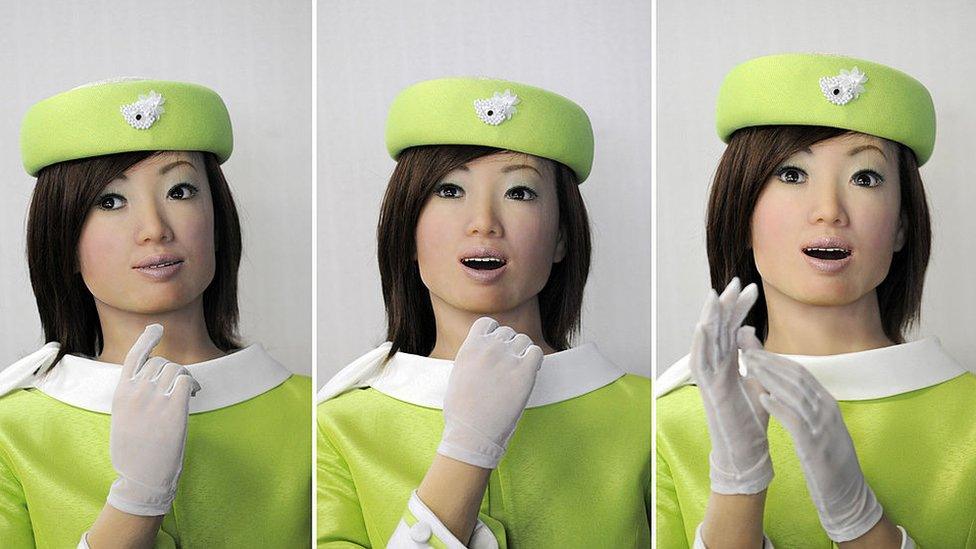

Japanese robot-maker Kokoro has created a robot receptionist for offices

Now, the robots have the accountants and lawyers in their sights. Growing numbers of us are likely to feel the white heat of technology.

That is accompanied by greater job insecurity - with a world of zero-hours contracts and the "gig economy".

For Ed Miliband, this threatens the assumptions behind the traditional welfare state, which was designed for a world of full-time work, mainly by men. The welfare state, he says, "has struggled to keep up".

"It's a very very binary old-fashioned 20th Century system in what feels like a significantly changing world of work."

To shore up public support for the system, politicians have become tougher on people receiving unemployment benefits. But many on the left are uncomfortable with the tough regime and see a universal basic income as a better solution.

"You end up with this whole architecture of interference, which actually doesn't enable people to fundamentally get out of this low pay, low security environment in which they're in," says Anthony Painter, of the Royal Society of Arts.

He argues that a guaranteed basic income would give individuals the security to retrain or try out new business ideas. It would, he believes, reward forms of work that are currently not remunerated - like caring for family members or volunteering.

Ed Miliband argues the universal basic income could give workers much more freedom

That security could change the power dynamics between worker and boss, and would enable employees to say no. "Suddenly the worker has the choice to be able to say, 'Well I don't want to take this job, and in fact I don't have to,'" says Mr Srnicek.

Interestingly, the idea of a universal basic income is also receiving support on the libertarian right - and indeed the free-market guru Milton Friedman was a fan of a similar idea. "It's a way of making the state much, much less invasive and much, much less powerful over other people's lives," says Sam Bowman, of the free-market Adam Smith Institute.

Find out more

Sonia Sodha presents Analysis: Money for nothing? on Sunday 17 July at 21:30 BST

Or listen via the BBC Radio 4 website, or download the programme podcast

He believes that it would help the transition for people in traditional jobs heading into the new economy. "I've heard this expression that automation and globalisation are like going to Australia: it's fantastic once you get there, but the journey can be really, really difficult."

Yet this support raises suspicions on the left. Do libertarians only like a universal basic income because they see it as a way of dismantling the furniture of the welfare state? And there are other objections. Labour MP Jon Cruddas sees the embrace of universal basic income as "absolutely deadly" for his party.

"Part of the thing about the basic income is that it assumes that the working class will disappear, right?" he asks. "Now if you disrespect them to that degree, is it any wonder that they'll go walkabout?"

Mr Cruddas warns that a left-wing embrace of the policy would constitute an electoral gift to UKIP, dismissing it as "a form of futurology which owes more to Arthur C Clarke than it does to Karl Marx".

"It imports a sort of passive citizenship with no sense of contribution. It doesn't contest the sphere of production, and it just retreats into a hyper-consumption."

Ed Miliband, for his part, sees this as a policy that deserves to be piloted to see if it could work. "I think the important thing about this idea is it's an idea not for next week or next month but it's an idea for five, 10, 15 years ahead. And the case has got to be built."

- Published5 June 2016

- Published16 December 2015

- Published20 August 2015