Boris Johnson: His rise, fall, rise, fall and rise

- Published

Gaffes and glory: Boris Johnson abroad

In the mad, gravity-defying career of Britain's new foreign secretary things move so quickly it is hard to keep up.

One day he is the most popular politician in the country, cheered by adoring crowds wherever he goes, on the verge of fulfilling his lifelong dream of becoming prime minister.

A few weeks later he has led an improbably successful campaign to get Britain out of the European Union and is being pursued down the street by angry voters, his career apparently lying in tatters after being knifed in the back by one of his closest allies.

No chance of No 10 now. No chance of redemption either, from a new prime minister who has always seemed to treat him with thinly veiled contempt.

Yet here he is again, a few days later, bouncing up Downing Street in his best suit and tie, to be handed one of the biggest and most important jobs in government.

It has been, to use the old cliche, a rollercoaster. Except, if it were a rollercoaster, Boris Johnson would manage to get stranded at the top of a loop, have to be rescued by paramedics, to ironic cheers from the crowd below, and then somehow turn the whole episode to his advantage.

It is a gift that very few politicians possess. But it does not begin to unravel the riddle that is Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson.

Any other politician who got stuck on a zip wire would have been humiliated - but not Mr Johnson

Boris Johnson - the basics

Age: 52

Marital status: Married with four children

Political party: Conservatives

Time as MP: Represented Henley, in Oxfordshire, from 2001 to 2008, and for Uxbridge and South Ruislip, 2015 to present

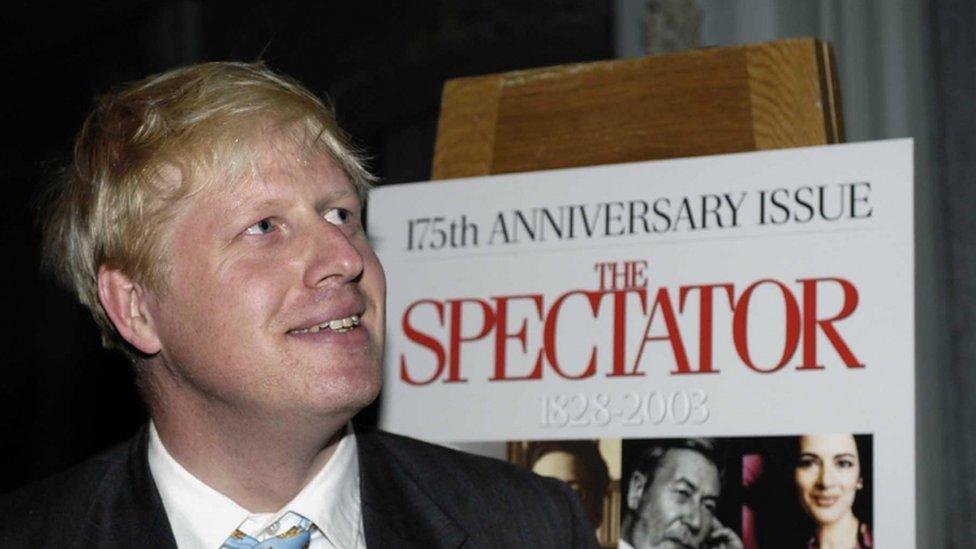

Previous jobs: London Mayor, Editor of The Spectator magazine; assistant editor, Brussels correspondent of the Daily Telegraph

For readers outside the UK, who might be puzzled by his appointment as foreign secretary, it is best not to think of him as a politician at all, in the conventional sense.

He found fame as a TV personality before he had achieved anything in politics.

His friend, journalist Rod Liddle, once said of his former editor: "Like all politicians, he is sometimes required to talk anodyne or disingenuous rot, but unlike the remainder, he cannot keep a straight face while doing this."

The British public warmed to this quality and it allowed him to get away with the kind of gaffes and indiscretions that would have sunk the career of other politicians many times over.

Pictures of him stranded on a zip wire, waving union jacks, during the 2012 London Olympics, were greeted with mirth, rather than derision.

But it would be wrong to think of Johnson as merely a clown.

A classics scholar, with a more supple mind than the average politician, he is someone with a deep understanding of politics and a fierce commitment to liberal, free-market economics.

As a man of Turkish ancestry, who was born in New York, spent part of his childhood in Brussels and who speaks several European languages, he is one of the most cosmopolitan figures in British politics - far from the Little Englander caricature that clings to some of his Brexit campaign colleagues.

His eight years as London mayor proved he could knuckle down to a serious job.

He was widely assumed to be motivated by a burning desire to be prime minister or, failing that, as he told his family as a boy: "The world king."

In his apparent determination to come across at all times like a minor character in a PG Wodehouse novel, with his tousled hair, rumpled suits and bumbling manner, he would always insist he had as much chance of becoming PM as being "reincarnated as an olive".

But in private, he was said to be a far more serious, and ruthless, figure. He comes from a high-achieving family. His younger sister Rachel is a high-profile journalist and younger brother Jo a government minister, and he had carefully plotted his path to the top.

It was in this context that the other side saw his last-minute decision to campaign for Britain's exit from the European Union.

He had previously been ambivalent about the EU. He had made a name for himself as a journalist in Brussels mercilessly mocking what he saw as petty EU rules and regulations but when it came to whether Britain should leave he sounded unsure.

In 2012, he said: "If we get to this campaign, I would be well up for trying to make the positive case for some of the good things that have come from the single market."

More recently, he had reportedly told friends: "The trouble is, I am not an 'outer'."

Gaffes and apologies

Mr Johnson is famed for his no-holds-barred approach to sporting contests

In his long career as a newspaper columnist and politician, Boris Johnson has managed to offend a wide variety of people and nations. Here is a selection.

On Tony Blair visiting Africa, in 2002: "It is said that the Queen has come to love the Commonwealth, partly because it supplies her with regular cheering crowds of flag-waving piccaninnies." He apologised for the use of the word "picanninnies" in 2008, during his successful campaign to be mayor of London.

In 2006, he said he would be happy to "add Papua New Guinea to my global itinerary of apology", after writing in a column that "for 10 years we in the Tory Party have become used to Papua New Guinea-style orgies of cannibalism and chief-killing".

The country's High Commissioner in London described the remarks as "an insult to the integrity and intelligence of all Papua New Guineans". Mr Johnson said: "I meant no insult to the people of Papua New Guinea who I'm sure lead lives of blameless bourgeois domesticity in common with the rest of us." adding that his remarks were "inspired by a Time Life book" which he claimed contained recent pictures of "Papua New Guinean tribes engaged in warfare, and I'm fairly certain that cannibalism was involved".

The following year he had this to say about Hillary Clinton, in a column praising her credentials as a future US president: "She's got dyed blonde hair and pouty lips, and a steely blue stare, like a sadistic nurse in a mental hospital".

During the EU referendum campaign, he got into a public spat with US president Barack Obama after a dig at his "part-Kenyan" ancestry.

He recently won a £1,000 prize for composing a rude poem about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. We can't print the poem in full, you can read it here, external - suffice to say, it includes a creative rhyme for "Ankara".

Anyone coming up against the former London mayor on a sports pitch would be well advised to keep out of the way - he famously flattened a 10-year-old boy during a game of touch rugby on a trade visit to Japan.

Mr Johnson's decision to lend his star power - and unrivalled ability to reach voters in all parts of the political spectrum - to the Brexit campaign was seen by those running it as a game-changing moment.

He became the face of Brexit in television debates and on the road in his bright red battle bus, a familiar, reassuring face who helped convince voters that quitting the EU was not as big a gamble as his old school friend David Cameron was claiming.

His ability to make Conservative free-market ideology sound liberating and even fun, rather than a dry exercise in accounting, was in full force, as he swept aside warnings about the likely impacts of Brexit as the products of a self-interested elite.

Election night in 2001 with wife Marina (far left)

But when the result went his way he seemed a little shell-shocked. His post-referendum news conference was notable for its absence of Johnsonian joie de vivre.

He spent the Saturday after the referendum playing cricket at the ancestral home of Princess Diana's brother, Earl Spencer. There was speculation that he was not focusing on the tasks ahead.

There was also speculation that he had not really wanted Britain to quit the EU at all, just to put up a good fight and be hailed as a gallant loser by Brexit-hungry Conservative Party members who would then vote for him in their droves when the time came to elect a new leader.

For the first time in his life, he had become a hate figure for many people. The man who was used to cycling around London to cheery waves and thumbs-up signs from taxi drivers, was now being barracked by angry voters accusing him of wrecking the country for his own vanity.

Whether this influenced his decision to pull out of the leadership contest - triggered by David Cameron's decision to stand down - is debatable.

His old friend and fellow Brexiteer Michael Gove's dramatic, last-minute decision to enter the race - declaring that he did not think Mr Johnson was up to the job - sealed his fate. It was a brutal political assassination, which was met with dismay by Mr Johnson's supporters.

Not for the first time in his life, he was contemplating the end of his political career.

In his own words

"Try as I might I could not look at an overhead projection of a growth-profit matrix and stay conscious," on his week-long career in management consultancy.

"Voting Tory will cause your wife to have bigger breasts and increase your chances of owning a BMW M3," on the campaign trail in 2004.

"If I was in charge I would get rid of Jamie Oliver and tell people to eat what they like," striking a blow for the right to eat pies at the 2006 Tory conference. He later described Oliver as a "national saint"

"I think if I made a huge effort always to have a snappy, inspiring soundbite on my lips, I think the sheer mental strain of that would be such that I would explode," - on his unique political style

"I think I was once given cocaine but I sneezed and so it did not go up my nose. In fact, I may have been doing icing sugar," after being questioned on TV panel show Have I Got News for You about drug use

"I have not had an affair with Petronella. It is complete balderdash. It is an inverted pyramid of piffle," on press reports of his relationship with journalist Petronella Wyatt. He would later be sacked from the Tory front bench for these comments

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (he is still known to family members as Al) was born in New York to English parents in 1964 and was, until recently, an American citizen.

He had an idyllic childhood spent, in part, on the family farm on Exmoor and in north London, where he attended the same infant school, in affluent Primrose Hill, as future Labour leader Ed Miliband.

In the early 1970s his father, Stanley, moved the family to Brussels after landing a job at the European Commission, in charge of pollution control.

Boris attended the European School in the Belgian capital, where he befriended his future wife Marina Wheeler, daughter of BBC journalist Charles Wheeler.

But in 1973, with his parents' marriage falling apart, he headed off to boarding school in England.

He shone at Ashdown House Preparatory School in East Sussex, developing a lifelong passion for Classics and winning a scholarship to the UK's best-known public school, Eton, where he quickly made an impression.

Mr Johnson gave up his editorship of the Spectator to focus on politics

His headmaster at the school which Prince William and Prince Harry were later to attend, Sir Eric Anderson, was also Tony Blair's housemaster during his schooldays at Fettes - often dubbed the Scottish Eton.

In 1983, Mr Johnson arrived at Balliol College in Oxford to study Classics.

He was already known for his sense of humour and his bumbling "old duffer" persona - but he also displayed a ruthless streak in his pursuit of his political ambitions.

He even briefly spurned his Conservative allegiances in favour of the then fashionable SDP as part of his successful campaign to be president of the Oxford Union.

He was also elected to the elite Bullingdon Club, famed for its hard-drinking, riotous behaviour.

Fellow members included his close friend Charles Spencer and the future Prime Minister David Cameron.

Pursued by the tabloids in 2004 as stories of an affair swirled round him

In one group photograph - which would later come back to haunt him - Mr Johnson is pictured lounging decadently in his £1,200 Bullingdon Club tailcoat, alongside Mr Cameron.

Halfway through his first year, he met and fell in love with Allegra Mostyn-Owen, a fellow student who also modelled for society magazine Tatler in her spare time.

In 1987 - when they were both 23 - he married Allegra in a grand ceremony at a Shropshire stately home, complete with an opera singer and a string quartet.

According to biographer Andrew Gimson's account, Mr Johnson managed to turn up in the wrong clothes - walking down the aisle in trousers belonging to Tory MP John Biffen - and lost his wedding ring within an hour of receiving it.

The marriage lasted less than three years, by which time Mr Johnson was beginning to make a name for himself as a journalist in Brussels.

His first attempt at forging a career, as a trainee management consultant, lasted a week.

His career in journalism very nearly fell at the first hurdle too, after he was sacked by the Times for making up a quote.

He had been trying to spice up a dull story about an archaeological dig but the editor - and the history don he "quoted", who also happened to be his godfather - failed to see the funny side.

He described the episode in an interview with the Independent in 2002 as his "biggest cock-up".

Johnson has become a full cabinet minister - complete with red box - for the first time

Luckily for him, the then Daily Telegraph editor, Sir Max Hastings, was prepared to overlook this indiscretion.

He took on Mr Johnson as a leader writer and then the newspaper's Brussels correspondent.

Mr Johnson took to his new role with relish, merrily debunking the stuffy European institutions his father had served as a commissioner and Tory MEP.

But disaster loomed again, when a tape surfaced of an old Oxford friend, Darius Guppy, who had been convicted of fraud, asking him to help locate a witness.

"He did not say yes, but neither did he say no," recalled Sir Max, who interrogated him about the tape which had been sent to the Telegraph anonymously.

"He evoked all of his self-parodying skills as a waffler. Words stumbled forth... never intended... old friend... took no action... misunderstanding," added Sir Max in the Observer.

He said he was satisfied Johnson had not been guilty of any impropriety and "dispatched him back to Brussels with a rebuke".

He was, by now, married to Marina Wheeler, his childhood friend from Brussels, who had become a successful barrister.

The two had never quite lost touch and after his divorce from Allegra, he set about pursuing her with characteristic persistence.

Their first child, Lara Lettice, was born in 1993, with three more children - Milo Arthur, Cassia Peaches and Theodore Apollo - following in quick succession.

On the campaign trail with David Cameron in 2007

He had stood unsuccessfully for the Conservatives at the 1997 general election, in the Labour stronghold of Clwyd South.

Two years later, when he was made editor of The Spectator, he told its proprietor at the time, Conrad [now Lord] Black, he would give up politics to concentrate full-time on the magazine.

But he continued to agonise over his decision in private, confessing to friend Charles Moore: "I want to have my cake and eat it."

In 2001 he stood for Michael Heseltine's old seat, Henley in Oxfordshire, and won.

But with The Spectator continuing to publish articles which proved embarrassing or irritating to some of his new parliamentary colleagues it was, perhaps, only a matter of time before Mr Johnson came unstuck.

It was an unsigned Spectator editorial, accusing the citizens of Liverpool of wallowing in their "victim status" over the murdered Iraq hostage Ken Bigley, that finally did it.

Tory chiefs were nervous about his first mayoral bid

The Tory leader at the time, Michael Howard, resisted calls to sack Mr Johnson. He had what turned out to be a far worse fate in mind - and dispatched his errant culture spokesman to Liverpool to apologise to the entire city.

The mission quickly descended into farce, however, as he was pursued by a media pack hungry for more gaffes. One reporter described it as an "Ealing comedy".

On a radio phone-in he was given a humiliating dressing-down by Paul Bigley, brother of Ken, who told him: "You're a self-centred, pompous twit - even your body language on TV is wrong."

He endured the ordeal, which he later dubbed Operation Scouse Grovel, with good grace.

But he was sacked by Mr Howard a few weeks later in any case, for allegedly lying over an affair with journalist Petronella Wyatt - something he vehemently denied.

When challenged about the relationship by the Mail on Sunday, Mr Johnson denied everything, calling stories about it an "inverted pyramid of piffle".

He suffered the indignity of being thrown out of the family home - and was hounded by the tabloid press as he went for a run wearing a skull-and-crossbones bandana.

Two of the most recognisable brands on British TV

Mr Johnson was seen as good copy, always ready with an amusing quip or a fresh piece of buffoonery, but any hopes of climbing higher up the political ladder seemed to be over.

The man who had dreamed of being in the Cabinet by the age of 35 watched as Mr Cameron, an Eton and Oxford contemporary two years younger than him, grabbed the Tory leadership.

Mr Cameron handed his old friend the junior role of higher education spokesman on the condition that he gave up editing the Spectator, which had seen its circulation soar under his guidance.

There was a new sense of seriousness about the way Mr Johnson tackled the higher education brief and it was a springboard to the job that would define his political career to this point - London mayor.

Mr Cameron had been determined to draft in someone from outside the party, preferably a well-known celebrity, to take on Labour incumbent Ken Livingstone as part of his efforts to broaden the Conservatives' appeal.

But when those efforts came to nothing, he turned to the party's own in-house celebrity.

He got down to the job of proving he was a serious candidate, displaying hitherto unseen levels of discipline, storming to victory over Mr Livingstone and gaining a huge personal mandate of more than a million votes.

Not everyone in London was pleased to see their mayor

As mayor, he championed liberal social policies, such as a living wage, and put his stamp on the capital by banning "bendy buses" and introducing a cycle hire scheme, which inevitably became known as the "Boris bikes".

He was a vehement opponent of a third runway at Heathrow airport, arguing instead for the construction of a new airport on reclaimed land in the Thames Estuary, a stillborn scheme that inevitably became known as "Boris island".

He was criticised for a lack of focus on detail and of failing to get to grips with some of the capital's long-term problems, such as a shortage of affordable housing, and for being slow to respond to the riots that swept the city in the summer of 2011.

But he proved to be a first class advocate for London as a vibrant, multicultural economic powerhouse. He toured the world banging the drum for London business and managing, most of the time, to avoid putting his foot in his mouth.

He was rewarded with a second election victory over Mr Livingstone in 2012, cementing his status as the most popular Conservative politician in the country.

Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson: "We will be working very closely with... the new departments for international trade and for the withdrawal from the EU"

Within weeks, he had the perfect stage on which to bask in his popularity in the London Olympics. He returned to the House of Commons at the 2015 election in the safe Conservative seat of Uxbridge and South Ruislip and - until his Brexit hiccup - looked on course to succeed David Cameron as prime minister.

His latest political comeback sees him getting a full cabinet seat for the first time - he had previously been a member of Mr Cameron's "political cabinet," which did not take policy decisions - and in one of the traditional "great offices of state".

Colleagues have argued that his new-found status as a "Europhile Brexiteer" may be what is needed, as he attempts to reassure the world that Britain is still an outward-looking nation.

Some wonder whether his gift for blunders will be his undoing, and that foreign dignitaries he meets in his new role will be left bemused, rather than charmed, by his very English brand of eccentricity.

On his first day in the job he described his mission as "reshaping Britain's global identity as a great global player" and stressed that just because the government would "respect the will of the people" and take Britain out of the EU it did not mean the country would be leaving Europe.

He brushed off questions about his past gaffes and insults, and negative comments about his appointment, saying it was "inevitable that there would be a certain amount of plaster coming off the ceilings in the Chancelleries of Europe" after Britain's Brexit vote, and they were "making their views known in a free and frank way".

Something he, of all people, would know plenty about.

- Published14 July 2016