Boris Johnson: Super ambassador?

- Published

Boris Johnson is not the first foreign secretary to be booed.

Lord Castlereagh, architect of the post-Napoleonic European order, was jeered in 1822 as he lay dead in his coffin, the crowd outside his Westminster Abbey funeral showing their anger at his domestic repression, not his diplomatic renown.

Geoffrey Howe was booed in Hong Kong in 1989 by local people fearful of Chinese rule.

Jack Straw was jostled and called a traitor when he visited Gibraltar in 2002 amid talks about joint sovereignty with Spain.

It is quite something, though, to be booed on your first full day as Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs.

Yet that was the fate that befell Mr Johnson as he attended a reception at the French embassy.

And there was worse. His French counterpart, Jean-Marc Ayrault, called him a liar.

And then within hours, he was expressing his shock and sadness at what he called the "appalling events in Nice and the terrible loss of life."

For a foreign secretary, this has been an extraordinary start to his term of office.

Gaffes

He has some baggage to shed, some newspaper columns to explain away, some rudeness to retract.

I particularly look forward to his apology for suggesting in a poem that the Turkish president had sexual relations with a goat.

His foreign forays as mayor of London produced gaffes and diplomatic incidents.

US Secretary of State John Kerry is due to meet Mr Johnson

His time as Brussels correspondent for the Daily Telegraph so annoyed the Foreign Office they set up a special team to deal with his anti-EU articles.

One could not dream up a candidate for foreign secretary who on paper appeared so inappropriate.

The Economist has concluded it is like "putting a baboon at the wheel of a Rolls Royce".

Yet this is to misunderstand both Mr Johnson and his appointment.

His past columns in the Telegraph should not be considered the new holy writ of British foreign policy.

Nimble

Some piece of whimsy he dreamt up on deadline is just that, a piece of commentary designed to entertain as much to inform.

I am sure there are hundreds of poor diplomats across Europe scouring the newspaper archives to glean Mr Johnson's views on the world. Yet this would be pointless.

For Mr Johnson qua journalist is nothing if not nimble on his feet. To paraphrase Groucho Marx, he has opinions and if you don't like them, he has others.

That is not to suggest, however, that Mr Johnson qua politician is without principle.

Mr Johnson will not be at heart of detailed Brexit talks

He has been appointed not because the prime minister wrote "F-Off" against his name and some civil servant misinterpreted her instruction (h/t Twitter), but because of his principles, above all for Brexit.

He - and Liam Fox at International Trade and David Davis at the Brexit department - have been put there to make it happen, to take responsibility for the compromises and concessions that that will involve, and then sell them to a sceptical electorate at home.

'Global player'

Theresa May has deliberately ensured that Brexiteers like Boris Johnson own the negotiations so there can be no cries of betrayal when the final deal is done.

Mr Johnson will not be at the heart of the detailed negotiations.

That will be the job of Mr Davis. But he will be at the heart of the operation to smooth furrowed brows in Brussels, to try to persuade continental chancelleries that Britain is changing its relationship with the EU not turning its back on the world.

That is the message Mr Johnson brought when he addressed his new staff at King Charles Street, that Britain wants to remain "a great global player".

Mr Johnson's role will be to fly the flag.

He did this for London with great success during the Olympics at the beginning of the decade: his task will be to try to do the same for Brexit UK at the end of the decade.

He will hope to be a kind of super ambassador, doling out Ferrero Rocher and reassurance around the world.

Nitty gritty

The gamble that Theresa May has taken is that Mr Johnson's charm and bonhomie will overcome the mistrust and the gaffes.

Mr Johnson's job, though, is not just Brexit. That will not happen for years.

In the mean time, like any other foreign secretary, he will spend many days on the Eurostar heading to Brussels for routine foreign affairs councils.

He will attend his first on Monday. And suddenly a man not known for his focus on detail will find himself discussing the nitty gritty of Syria and Libya with the US Secretary of State John Kerry over breakfast.

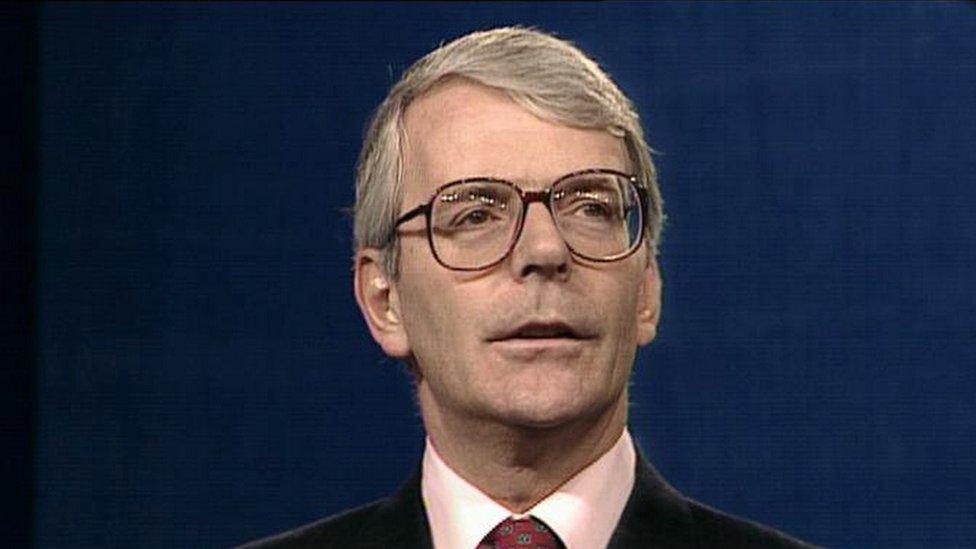

Sir John Major took time to read into the foreign secretary role

With his EU colleagues, he will discuss relations with Cuba, the peace process in Colombia and the crisis in Venezuela. Oh, and China and migration within the EU will also be on the agenda.

And it is here that Mr Johnson's actual views will matter.

What does he really think about the EU's policy towards Russia? Should sanctions on Moscow be retained as strongly as now?

He has in the past been critical of the EU's policy towards Ukraine. What are his real views about Turkey and its fight against the Kurdistan Workers' Party or PKK, an organisation for which he has in the past showed some sympathy?

What are his views on the conflict in Yemen where British support for the Saudi-led offensive has not been without controversy?

How much support does he think Britain should give to President Rouhani in Iran amid weak economic growth and rising support for the fundamentalists?

He has in the past backed Tehran having a nuclear weapon. And where does he stand on Libya?

Does he place Britain's diplomatic eggs in the fledgling administration in Tripoli? Or does he flirt with other power centres in the east of the country?

Will he court China with as much enthusiasm as George Osborne?

Colourful grandstanding

Of course, British foreign policy in recent years has been formulated largely in Downing Street and the national security apparatus that David Cameron set up around him. And that is expected to continue under Mrs May.

But these are all issues where Boris Johnson's opinion matters because it will be he who is sitting at the top table with the likes of John Kerry and Sergei Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister.

It is here that the detail matters. It is here that the hard graft has to be done.

The last foreign secretary, Philip Hammond, lapped this stuff up and gained the respect of his counterparts. This is now the challenge for his successor.

Colourful grandstanding in the name of Britain has to be matched by serious and credible negotiation in the national interest.

When John Major was appointed foreign secretary in 1989, he grabbed all his briefing papers and headed off to a colleague's holiday home in Spain.

For several weeks he sat by the pool and read, and returned to London the most informed newly appointed minister FCO officials had seen for years.

Boris Johnson will not have that luxury of time in which to do his homework.

And unlike John Major, he will hope to stay in the job for more than three months.

- Published26 June 2016

- Published26 June 2016

- Published30 June 2016