Premiers past: What now for Cameron?

- Published

It is a curious fact, but the prime minister never actually has possession of the keys to No 10 Downing Street.

So, having metaphorically handed them over to Theresa May, what now for David Cameron?

Having achieved the highest office in the land at the age of 43, and departed six years later, what next for a man a few months shy of his half-century?

Here is a guide to the futures of prime ministers past.

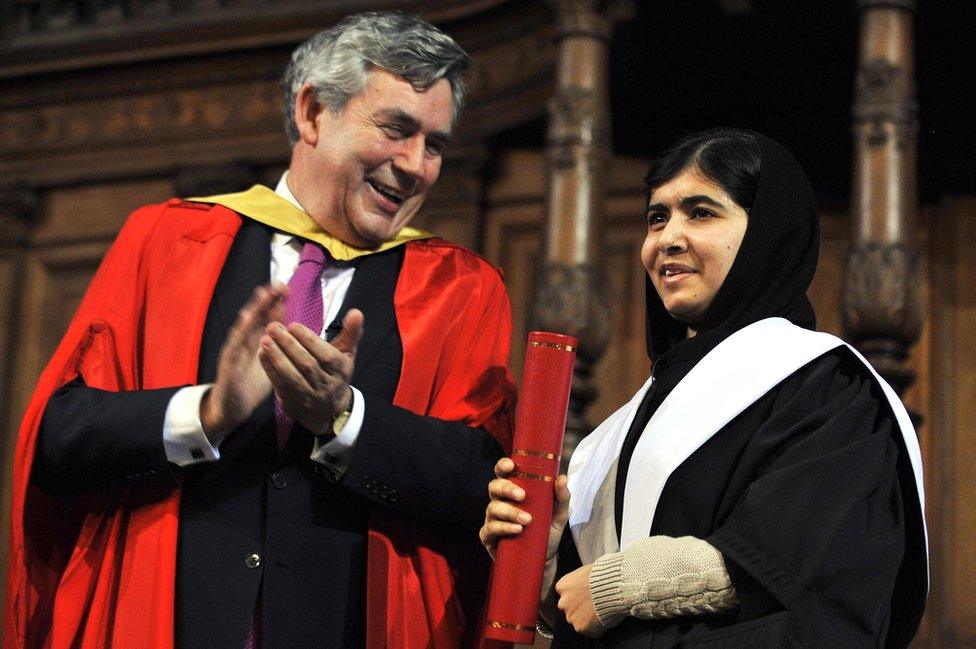

Gordon Brown: Left office 2010

Gordon Brown, here with Malala Yousafzai, has chosen to focus on young people

The constituents of Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath might have felt a little hard done by from May 2010 to May 2015, as the former prime minister was rarely to be seen in the Commons chamber.

In addition to becoming a board director for the World Wide Web Foundation and an unpaid advisory role at the World Economic Forum, he was a UN special envoy on global education.

He wrote the book Beyond The Crash, which covered the global financial crisis, in just 14 weeks and made a high-profile intervention in the Scottish independence referendum campaign in 2014.

Ultimately, Mr Brown's former constituency, a safe Labour area for the previous eight decades, fell to a resurgent Scottish National Party.

Since then, he has taken his first private-sector role, as an adviser to the US-based investment management company Pimco, his fee going to the Gordon and Sarah Brown Foundation to support charity work.

Tony Blair: Left office 2007

Tony Blair has spent much of his time in the Middle East

After leaving Downing Street, Mr Blair stepped down from the parliamentary seat of Sedgefield, triggering a by-election, which Labour won comfortably.

He was soon confirmed as a Middle East envoy for the United Nations, the European Union, the United States and Russia, a role he held until May 2015.

He also established Tony Blair Associates, providing strategic advice on political and economic trends and governmental reform, with profits going to support Mr Blair's work on "faith, Africa and climate change".

But he has faced criticism for providing advice to the Kazakhstan government, which has been criticised for its human rights record.

Two foundations have been set up in his name, the Tony Blair Sports Foundation and the Tony Blair Faith Foundation, and a charity called the Tony Blair Africa Governance Initiative.

Mr Blair has also found time to detail his memoirs, with an autobiography entitled A Journey, income from which has been donated to a sports centre for injured service personnel,

It is claimed that he has earned up to £100m since leaving office.

Mr Blair himself suggests a closer figure would be about a fifth of that sum.

Most recently, he has come in for criticism following the conclusion of the Chilcot report on the inquiry into the Iraq War, which criticised the former prime minister for not exhausting all efforts to find a peaceful solution before going to war.

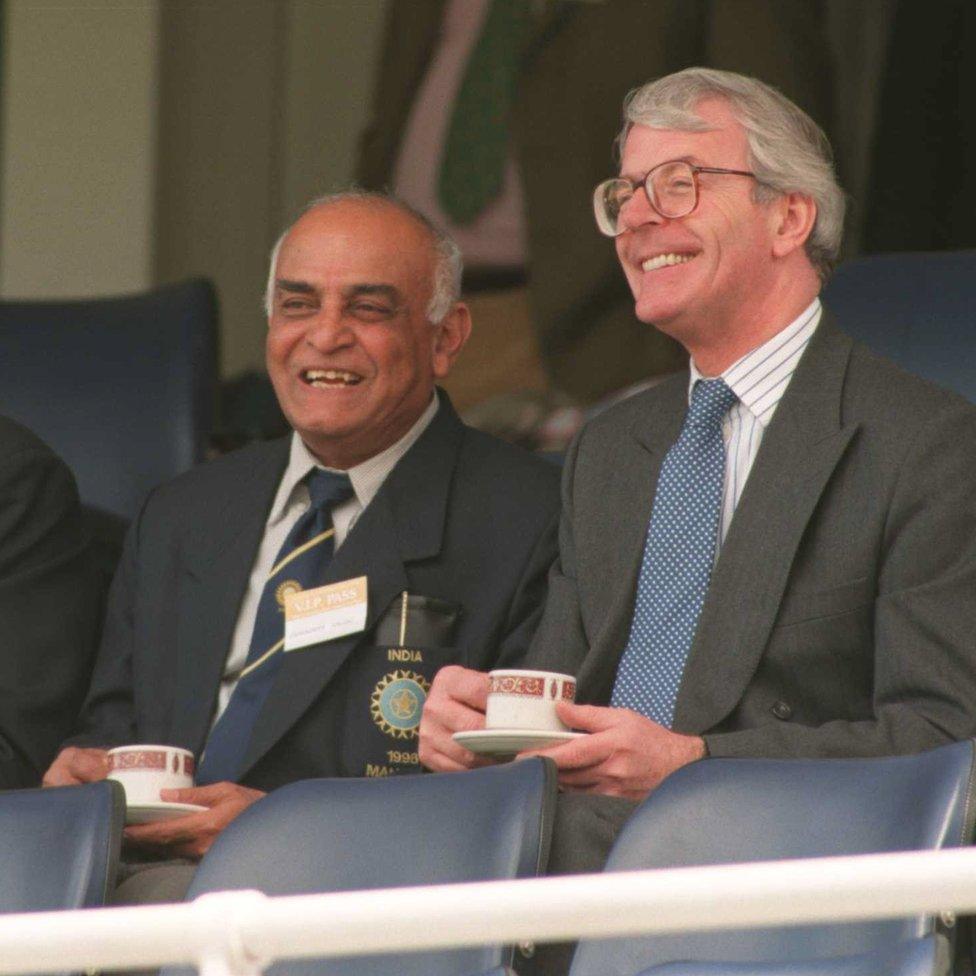

John Major: Left office 1997

John Major has devoted a good deal of energy to supporting and watching cricket

John Major served as a backbencher through the four-year parliamentary term, after losing the 1997 general election to Tony Blair,

Known for his love of cricket, he was president of Surrey County Cricket Club until 2002 and in 2005 was elected to the committee of the Marylebone Cricket Club.

Sir John was knighted in 2005, the last prime minister so far to receive that honour, but has refused any offer of a peerage.

In 2002, his affair with Edwina Currie was revealed in her autobiography.

He is a popular after-dinner speaker, and chaired the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust.

Sir John was a prominent campaigner for remaining in the European Union, and has served as president of the Bow Group and Chatham House.

Margaret Thatcher: Left office 1990

Margaret Thatcher went to the Lords and continued to influence Tory policy

Following the coup that removed her from Downing Street, she remained an MP, representing Finchley until the 1992 general election, when she was ennobled as Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven.

She became the first former prime minister to set up a foundation, although the British wing of it was dissolved in 2005.

She was hired by the tobacco company Philip Morris as a "geopolitical consultant" and continued to speak out on political issues.

Baroness Thatcher wrote two autobiographies - The Downing Street Years and The Path to Power - and, in 2007, became the first living prime minister to be honoured with a statue in the Palace of Westminster.

Periods of ill health followed, though she continued to make a few choice public appearances.

She died in April 2013, at the age of 87.

James Callaghan: Left office 1979

Callaghan, seen here with Margaret Thatcher, became the longest living former premier

After the 1979 election defeat, Callaghan remained Labour leader during the subsequent transition phase, the last leader of note to do so.

He jointly founded the AEI World Forum alongside friend and US President Gerald Ford in 1982.

Callaghan became Father of the House in 1983, before standing down from his Cardiff South and Penarth seat at the 1987 general election.

That year, he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, and published his autobiography, Time and Chance.

The longest-living former British prime minister died, one day short of his 93rd birthday, in March 2005, 11 days after the death of his wife, Audrey.

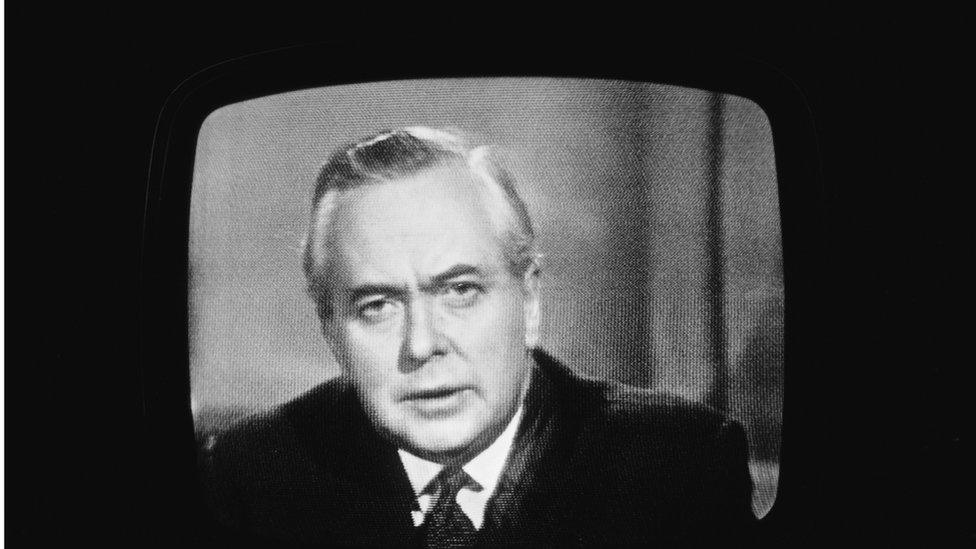

Harold Wilson: Left office 1976

Wilson recognised the power of television, and went on to have a brief career as a TV host

Wilson unexpectedly announced his resignation just days after his 60th birthday.

Notably, the Queen came to dine at Downing Street to mark his resignation, something she had previously done only for Sir Winston Churchill.

He continued as MP for Huyton until 1983, balancing that role with being signed up by David Frost to host a chat and interview TV show.

After leaving the Commons, he joined the board of trustees of the D'Oyly Carte Trust and, after being raised to the peerage as Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, was a regular attendee in the Lords. He died in May 1995.

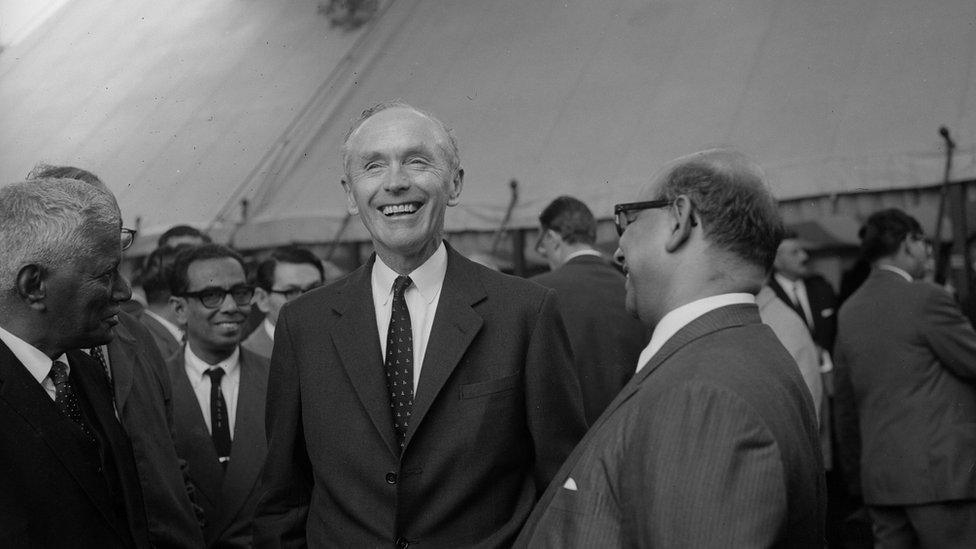

Edward Heath: Left office 1974

Edward Heath was perhaps most content on his yacht, Morning Cloud

Of all the former prime ministers, Heath was the stayer, serving the people of Old Bexley and Sidcup from the backbenches for well over a quarter of a century after he left No 10.

He resigned the premiership in 1974, allowing Harold Wilson to form a minority Labour government, and lost the Conservative leadership to Margaret Thatcher the following February in a bitter internal contest.

While still popular within the party, Heath's relationship with Thatcher - famously characterised as "the longest sulk in British political history" - was frosty, and he turned down offers to become Britain's ambassador in Washington, and secretary general of Nato.

And he criticised both the Thatcher and Major governments when he felt it was necessary.

In 1990, Heath flew to Baghdad to secure the release of British nationals held hostage following the invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein's Iraq.

Knighted in 1992, he became Sir Edward. In the same year, Heath also became the Father of the House, finally retiring from Parliament at the 2001 election, aged 84. He died aged 89 in July 2005.

Alec Douglas-Home: Left office 1964

Douglas-Home was Foreign Secretary both before and following his time as premier

After the loss of the 1964 election, Alec Douglas-Home remained as MP for Kinross and Western Perthshire and leader of the opposition for a further year before he resigned the latter role.

New Conservative leader Edward Heath gave him the shadow foreign affairs portfolio and then the Commonwealth relations brief.

When Heath became prime minister, he resumed the role of foreign secretary, the post he had previously held under Macmillan, from 1970 to 1974.

Following the defeat to Labour, he relinquished his seat and returned to the Lords as a life peer.

In retirement, he spent his days with his family and fishing, as well as writing three books.

He died at the age of 92 in October 1995.

Harold Macmillan: Left office 1963

Macmillan and his wife, Dorothy, in the grounds of their country home, Birch Grove House

"Supermac" stayed on as an MP for a year following his resignation as prime minister, due to ill-health, in 1963.

He remained as chancellor of Oxford University, a post to which he was elected in 1960 and in which he remained until his death

In 1964, he became chairman of his family firm, the publishers, Macmillan. In a decade at the helm, the company published his six-part autobiography.

Having initially resisted the customary offer of a role in the House of Lords, he was granted the last hereditary peerage given to a prime minister, as the Earl of Stockton and Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden.

But he voiced criticism of Margaret Thatcher's handling of the coal miners' strike in his maiden speech in the Lords, and he continued to be an occasionally critical thorn in her side until his death in December 1986 at the age of 92.

Sir Anthony Eden: Left office 1957

Anthony Eden could not escape the legacy of Suez, but became a critic of US policy in Vietnam

A combination of the Suez crisis and illness led to Anthony Eden's resignation as prime minister. After initially considering a return to Parliament, he instead became the Earl of Avon in 1961.

He served as chancellor of the University of Birmingham, bred cattle at his Wiltshire farm, published four volumes of political and personal memoirs covering his political life, and particularly made headlines when criticising US involvement in Vietnam.

He died as a result of liver cancer in January 1977 at the age of 79.

Sir Winston Churchill: Left office 1955

Winston Churchill was both artist and historian

Ill health resulted in Winston Churchill's resignation during his second term as prime minister, following a stroke, his second, in 1953.

He continued as MP for Woodford for a further two parliamentary terms, but his appearances became less frequent over time.

Nevertheless, he remained actively interested in politics, particularly foreign affairs.

He divided his time between his home in Chartwell, London and the French Riveria.

He died following another stroke in January 1965, and was given a state funeral in recognition of his role as Britain's wartime leader.

Clement Attlee: Left office 1951

Clement Attlee visited China as Labour leader after he left office

After losing the 1951 election, Clement Attlee battled on to remain leader of the Labour Party in opposition, unsuccessfully fighting the 1955 election.

Only then did give up the leadership, after holding the post for more than 20 years.

He became Earl Attlee and took his place in the Lords.

In retirement, he continued to make an impact, most notably through his support for the decriminalisation of homosexual acts by consenting adults in private.

He helped to set up the Homosexual Law Reform Society in 1958, which ultimately led to the law being changed by the Sexual Offences Act in 1967.

He died that year at the age of 84.

- Published12 September 2016

- Published9 July 2016

- Published13 July 2016