Are political parties out-of-step with UK voters?

- Published

It has not been a great week for the cause of internal democracy in political parties.

Last week, UKIP's ruling body excluded one of the better known candidates to succeed Nigel Farage because his application missed by the deadline by 17 minutes.

Three members of the executive promptly resigned, one of them telling the BBC the party was in a fight for its very survival.

"There is a huge amount of confusion, flux and sadly infighting," Steven Woolfe, the excluded candidate, told me, as he pinned the blame on the executive.

Over at the Labour Party, the mood is, if anything, more poisonous.

After its National Executive imposed a retrospective cut-off date for party members to be eligible to vote in next month's election, it was challenged in court and lost.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of each case, from the outside it does not look great for those who ask us for our votes on polling day to appear to be narrowing the choice in their own internal elections.

Steven Woolfe, excluded from the UKIP leadership ballot, says there is much infighting in the party

There are plenty of reasons to wonder whether the political parties are increasingly out-of-step with the voters.

The European referendum is only the latest example.

There is much to be said for maintaining your principles even when they are not popular.

So, the Liberal Democrats say they will campaign at the next general election for the UK to be in the EU.

Two peers are reported to have resigned the party whip in protest, perhaps aware that it might not increase the chances of a Lib Dem revival to set its face against the - albeit narrow - decision of a majority of those who voted.

Last year's general election result has not filled any of the parties with confidence, with perhaps the exception of the SNP.

Labour's recovery from one of its worst ever results - in 2010 - consisted of increasing its share of the vote by 1.5%, and losing seats in the process.

The Liberal Democrat share collapsed from 23% to just under 8%.

Its 57 MPs were reduced to eight.

Those two parties, as well as the Conservatives, were all but eliminated from Westminster's Scottish constituencies.

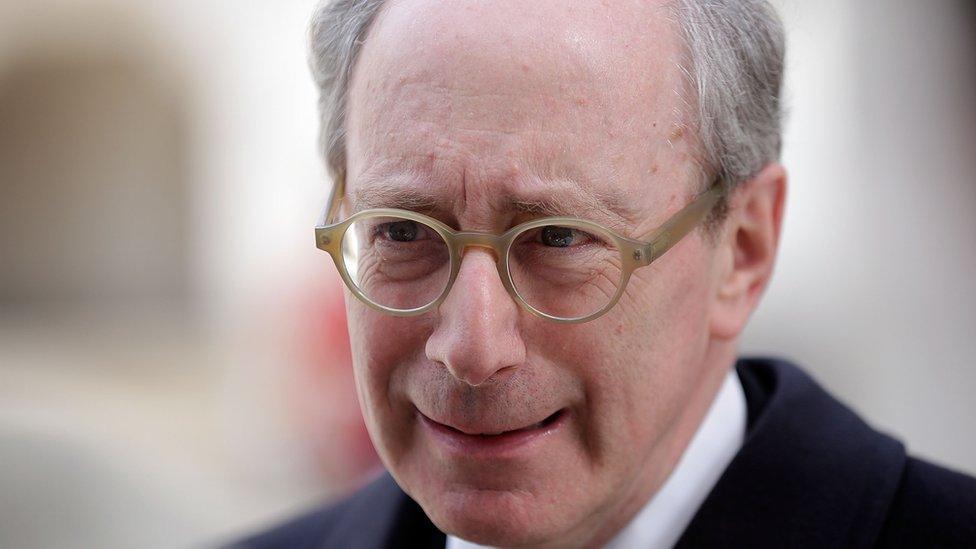

Former Foreign Secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind believes the Conservative Party is not as strong as the polls imply

Even UKIP, which took close to four million votes, finishing third overall, ended up with only one MP.

Divided oppositions do not win elections, but they help to hand power to those that do.

David Cameron has bequeathed to his successor, Theresa May, a majority Conservative government, even though the Tories won just shy of 37% of the vote.

"The Tory party is not as strong as the opinion polls might imply," Sir Malcolm Rifkind, the former Foreign Secretary, said.

But he believes the threat to the party's unity posed by Europe has passed.

Although there are divisions even among supporters of Brexit over what deal the UK should negotiate as it leaves the EU, he doubts they will lead to any kind of split, not least because of the cohesive effect on parties of being in power.

"Why is the Tory Party the world's oldest political party?" he asked rhetorically.

"It has been around for 300 years.

"Of course there have been divisions, but the Tory party basically does not have an ideology.

"It has never had an ideology.

"It occasionally has an existential problem, and it does not have one now."

Jenny Willott, one of those Lib Dem MPs ousted in 2015, thinks both her party and UKIP have one advantage compared with the others, a clear and consistent position on the EU.

Former Lib Dem MP Jenny Willott thinks the Brexit negotiations could highlight internal Conservative and Labour divisions

She thinks the Conservatives and Labour could be hit by divisions over the Brexit negotiations, and at the next general election that could become a cause more important than party.

"We may see people not just standing on the old ticket, so that we have a Labour candidate, a Lib Dem, Tory, UKIP, whatever; I think we might actually see people defining themselves much more clearly as to where they stand on Europe," she said.

The European Union was one of those issues of consensus in the mainstream of British politics; even sceptics such as Sir Malcolm or Jeremy Corbyn still believed the UK should remain in.

Another was light-touch financial regulation, the failure of which exacerbated the effects of the financial crisis.

Faith in the judgement of political elites follows the decline in the "broad church" appeal of political parties.

If there ever was a correlation between income, class and voting, it looks pretty threadbare now.

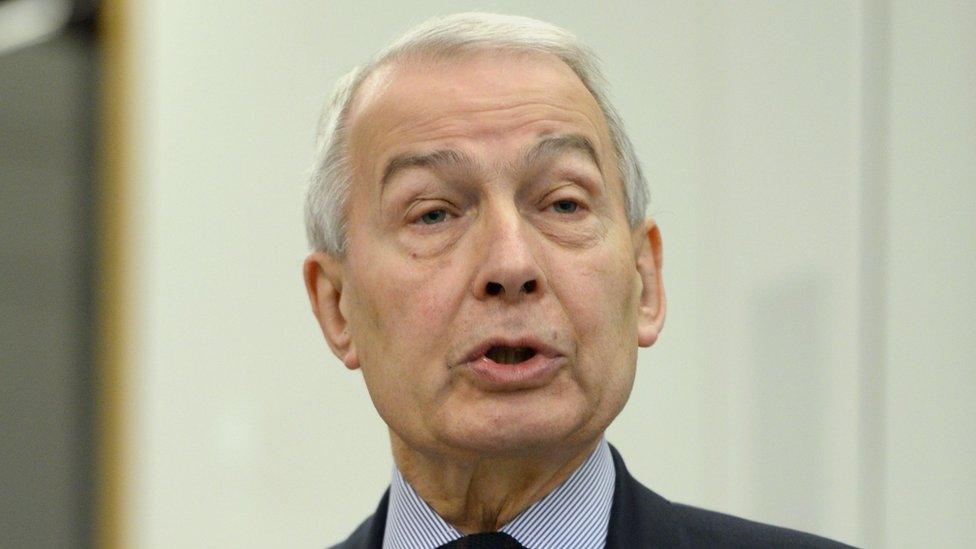

It is this combination of factors which has made Frank Field, a Labour MP since 1979, sceptical about his party's chances.

Never known for his respect for consensus in politics, Mr Field believes UKIP is "threatening to kill the Labour Party".

Assuming it can overcome its leadership problems, he fears UKIP could do to Labour south of the Scottish border what the SNP has done north of the border.

Labour MP Frank Field argues that many Labour voters no longer have a natural affinity with the party

"If they reshape themselves as the English Party, then there is a real danger that the million voters who previously voted for us in the last election who moved over to UKIP," he said, could be followed by others, "making it impossible for us to be a serious party of opposition challenging for government."

Mr Field said it was not a case of UKIP "stealing" Labour's vote; this passionate EU-sceptic believes there is not what people used to term a "core vote" to steal.

"There clearly is a very, very large section of the Labour vote that does not actually feel natural affinity with Labour any more," he said.

"They are more concerned about the sense of place, of identity, of country."

As Labour MPs agonise about whether or not to split from the parliamentary party in the event of Jeremy Corbyn winning the leadership election, Frank Field fears they may be missing the point.

"We can have this top-down approach that we had with the Gang of Four, the founding of the SDP," he told me.

"We might well do that, but I do not think anybody's listening.

"The key thing that is happening is that voters are moving."

In what direction and who will be there to meet them when they arrive is a question no party politician can answer; no wonder they are so nervous.

As a leading figure in the French Revolution is said to have remarked: "I am their leader and must follow them."

Shaun Ley presents The World This Weekend during the summer, at 13:00 BST on Sundays, and afterwards available on the BBC Radio 4 website.