Why UKIP is talking about seaweed

- Published

"We've had quite a problem with seaweed," says UKIP councillor Lin Fairbrass

What's the first word that comes into your mind when you think of UKIP?

Let me guess: it is probably not seaweed.

And yet here I am, not entirely appropriately dressed in the regulation uniform of the Westminster reporter, a suit and tie, walking along the beach in Broadstairs, in Kent, and talking about green and smelly matter from the deep.

I am in the company of Cllr Lin Fairbrass, the deputy leader of Thanet District Council.

Cllr Fairbrass sports purple glasses and strands of purple hair. She is UKIP to the scalp.

Both, she tells me, predate her election as a UKIP councillor - her colour scheme and that of her party a happy coincidence.

Rotting oceanic vegetation rots beneath her feet. Its removal is now top of her mind.

'A big deal'

"It is a big deal," she says. "We've had quite a problem with seaweed over the last few weeks.

"It comes in on the tide. Thanet District Council has cleared hundreds of tonnes from our beaches over the last few weeks. Unfortunately we clear it and then the tide brings in another lot!"

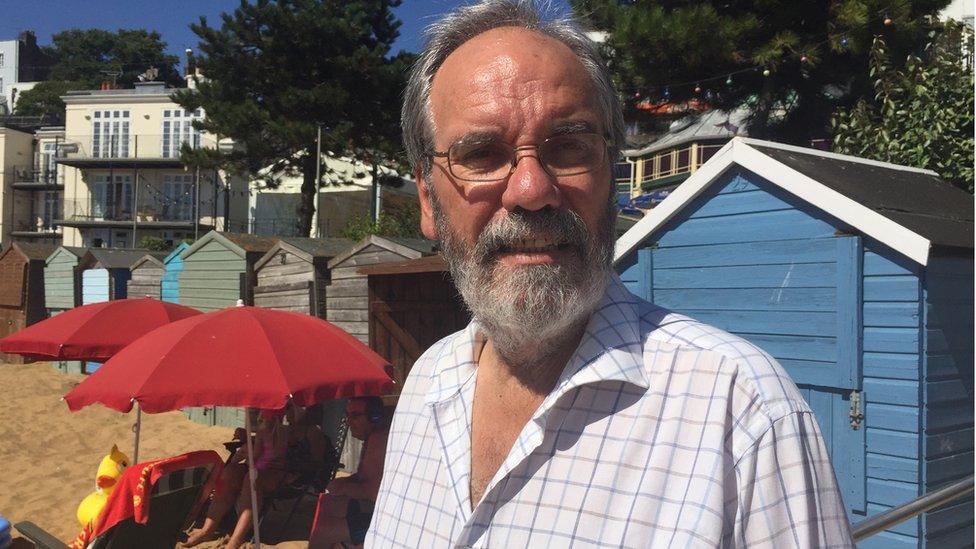

The "not entirely appropriately dressed" Chris Mason

Did you spot the word "we" in the quote from Cllr Fairbrass there?

Yes, UKIP is in charge here: it runs the local authority.

"If you're down the beach one day and the council comes and clears it in the evening, and you come back the next day and the tide has brought in another lot, you don't think the council has done anything about it," Cllr Fairbrass adds.

That, I suggest, is the reality, when an anti-establishment party becomes the establishment.

"It is," she acknowledges.

Fertile territory

Fast forward a few years from now and the most fertile territory for UKIP, when it comes to winning elections, will have gone: the European Parliament.

Once the UK leaves the EU, no MEPs will head to Brussels and Strasbourg from here.

Which leaves Westminster, where UKIP has just one MP, the Welsh Assembly, where it has a foothold, and local government, where it runs one council: this one.

Thanet's UKIP council leader says the UK needs to "look to the east" for future trade relationships

And leaving the EU also leaves the party with a welcome challenge but a big one: what on earth does it stand for now?

In a nearby cafe, Cllr Christopher Wells, the leader of Thanet District Council, offers his answer.

"The one thing that campaigns of the last 20 years have taught us is that people don't trust the old politics any more and there is a vision to develop about where we go in the world, post EU," he says.

"I think my instinct for that vision is to re-establish many of the traditional relationships we had with Commonwealth countries and in addition to that to understand, and really make sure everyone understands, the economic power in this world went to the east.

"We need to look to the east in terms of making those trade relationships work."

And what, I ask, about UKIP's future prospects?

"Certainly in pure electoral terms, it is the Labour Party where we are going to actually take votes from. That's what we did down here in Thanet. It was quite clear that traditional Labour, white working class supporters are not at all happy and are looking for someone else to represent their views."

Punch and Judy politics

I suggest it all sounds rather like the strategy of the Liberal Democrats in the 1990s, building local powerbases.

"I don't think we will follow the same trajectory of the Lib Dems as such, but I think certainly we need to build a base, and if there is a weakness in where we've been for the last 20 to 25 years, it is being wedded to that one single policy [of leaving the EU]," he says.

'UKIP 2.0'

But what about the policy offer, the political pitch to the punters?

"I think if you were to look across Europe at possible models for UKIP 2.0, you might look at the Five Star Movement in Italy led by the former comedian Beppe Grillo," says UKIP watcher Prof Matthew Goodwin, from the University of Kent and Chatham House.

"It is anti pretty much everything. Anti-EU, anti-elite, anti-globalisation. It is a model that many senior UKIP activists have been looking at not only in terms of its ideas but also as a model of party organisation."

But Prof Goodwin concludes on a cautionary note for the party.

"UKIP now in a post Nigel Farage era, in an era when it's lost most of its competent activists, I think is really going to struggle to do all the things we saw it do between 2010 and 2016."

Mind you, UKIP has proved people wrong in the past.

It has now got to try to do it again.