G20: Theresa May navigates changing UK role on international stage

- Published

As first days go at an international school, the G20 passed off alright for the new pupil.

Theresa May met all the right people, the language differences did not trouble her and she refused to allow the big boys to bully her behind the bike sheds. The prime minister held her own.

At the end of the two days, she had managed to speak to almost all the world leaders at the summit. They were interested because she was an unknown quantity and that rare beast, a European leader who is likely to be around for a while.

They were also keen to hear what she said about Brexit. She assured them that Britain was open for business and said she had had "pleasing and useful" discussions about future trade deals, in particular with India, Mexico, South Korea, Singapore and Australia.

Mrs May avoided a row with Chinese leader Xi Jinping by promising a decision on Hinkley Point within a month

She floated a few ideas of her own: the need for G20 countries to do more to stop foreign fighters dispersing to new failed states once they were squeezed out of Libya, Iraq and Syria; and the need for G20 countries to ensure that the global economy spreads wealth more fairly, an issue the Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, called "civilising capitalism".

She also banged the drum for free trade, an increasingly lonely message as electorates around the world urge their leaders to greater protectionism.

The prime minister also made it abundantly clear to her fellow leaders that she won't be rushed on Brexit or Hinkley Point, the delayed nuclear plant in Somerset that China wants to invest in as an entree into the UK energy market. She dodged a row over this here by reassuring the Chinese there will be a decision by the end of this month.

The message in Hangzhou was clear: Theresa May is her own woman, the Cameron era is over.

And yet this summit was in truth not dominated by Brexit and the first signs emerged that Britain is not quite as prominent as it perhaps once was.

The real debate was about the changing balance of power between China and the US, as evidenced by the spat over protocol and the media when President Obama arrived at the airport; the continuing uncertainty over how to fix the sluggish global economy; the fruitless talks between the Russians and the Americans over a possible cessation of hostilities in Syria; and even the regional tensions sparked by yet another missile test firing by North Korea.

US President Barack Obama said the UK wouldn't be prioritised in free trade talks

Brexit was a cloud on the G20 horizon, not a current storm.

And what interest there was in Mrs May was focused on people's fears about the risks of Brexit. Leaders wanted to know what it would mean for them and Mrs May had few answers. The Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, in particular, made it very clear to her that his country's firms in Britain wanted more certainty.

One Italian minister effectively threatened a trade war if EU nationals were stopped entirely from working in the UK.

And President Obama was blunt in telling her that Britain would indeed be at the back of the queue when it came to trade deals, behind the EU and countries around the Pacific. The one moment of comfort for Mrs May came when she spotted her old university friend, Malcolm Turnbull, who was gushing in his promise of Australian trade deals and negotiating expertise.

And there are signs that the US and the EU are beginning to caucus without the UK round the table: President Obama and his Secretary of State, John Kerry, chose to meet Chancellor Merkel of Germany and President Hollande of France together without inviting Mrs May.

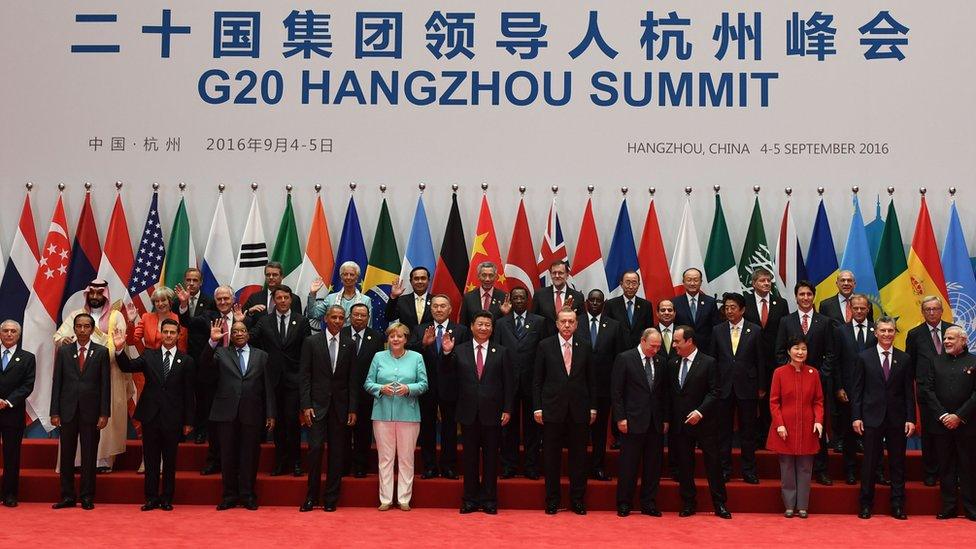

The official summit photo; Mrs May far left

And in the official summit "family photo" Mrs May was placed at the distant far left, as befitted either her status as a newcomer or perhaps Britain's status post Brexit.

Mrs May insisted that Britain was still playing a "full role" in global politics. It is a role that is certainly changing.

- Published4 September 2016

- Published4 September 2016

- Published4 September 2016

- Published24 July 2016