Boundary changes: Why UK's political map is being re-drawn

- Published

The UK's political map is set to be redrawn in the run-up to the next general election in 2020.

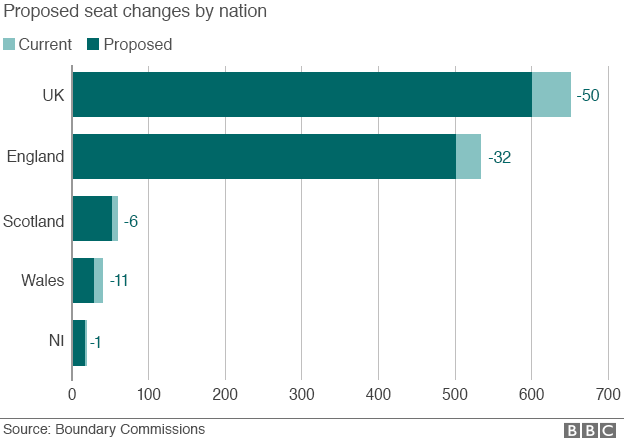

Under draft plans just published, the number of parliamentary constituencies will fall significantly, reducing the number of MPs in Parliament by 50 to 600, while most seats will change in size and character, for the first time in at least a decade.

The shake-up - drawn up by the independent Boundary Commissions of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - will pit existing MPs against each other for re-election and could have a big impact on the outcome of the 2020 poll, as well as the internal dynamics of the leading parties, particularly Labour.

We've just had an election - why is this all happening?

David Cameron and Nick Clegg agreed the changes in 2011 but then fell out over them

Each MP in Parliament represents a different constituency and is elected by residents of that geographic area.

The law requires the size and shape of parliamentary boundaries to be periodically reviewed to keep with up demographic changes influencing the number of eligible electors in each area as well as other factors such as local administrative arrangements.

The last review took place in the mid-noughties in time for the 2010 general election.

Plans for a further review in 2013 were shelved following a dispute between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats over reforms to the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The current review is based on proposals that were initially agreed by the coalition government in 2011 but subsequently put on hold.

What was the thinking behind having fewer MPs?

The changes will mean an extra bit of room on the hallowed green benches

Back in 2011, it was described as a rare instance of turkeys voting for Christmas. The fact that MPs backed plans to reduce their number by 50 was in itself pretty remarkable.

Despite being an arena of fierce political combat, the Commons also remains something of a club where all its members - whichever party they represent - are bound by a set of common rules and privileges and defend their interests with a hawk-like intensity.

Many MPs are against the changes on principle, believing they are already over-stretched and that this will further increase their workload, making it harder for them to do their job representing their constituents and holding ministers to account.

So why did it happen? Well, remember it was not too long ago that MPs were in the collective doghouse and Parliament's reputation was tarnished by the 2009 expenses scandal.

Mr Cameron was pushing at an open door with his call for the number of MPs to be cut to reduce the cost of politics, something which also fitted in with the self-declared age of austerity.

The fact that the changes were seen as benefitting the Conservatives must also have helped ensure the proposals went ahead.

The plans are controversial - why?

A number of constituencies will be abolished while others will change markedly

Although some Conservatives now risk losing their seats, the changes - which will see constituencies more closely equalised in terms of size - could affect Labour the most.

Many experts believe the shake-up goes some way to remedying anomalies in the system - such as the disparities in constituency sizes which means MPs need different amounts of votes to get elected - which were historically unfair on the Tories.

But Labour claims the opposite, accusing the Conservatives of seeking to gerrymander the boundaries to their own political advantage.

Their argument is that requiring all seats - bar two on the Isle of Wight as well as Na h-Eileanan an Iar and Orkney and Shetland - to have an electorate within 5% of the 74,679 average, discriminates against them since many of their seats are in inner-city areas in the north-east and north-west of England, where population levels have been stagnant or falling and there are comparatively low levels of electoral registration.

They are also unhappy that the Commission's calculations about average constituency sizes are based on voter figures which predate the EU referendum.

At the official cut-off point of 1 December 2015, there were 44,562,440 people eligible to vote in the UK. That figure is now at least 2.5 million higher after the rush to register to take part in the historic EU vote.

Who are the big names affected?

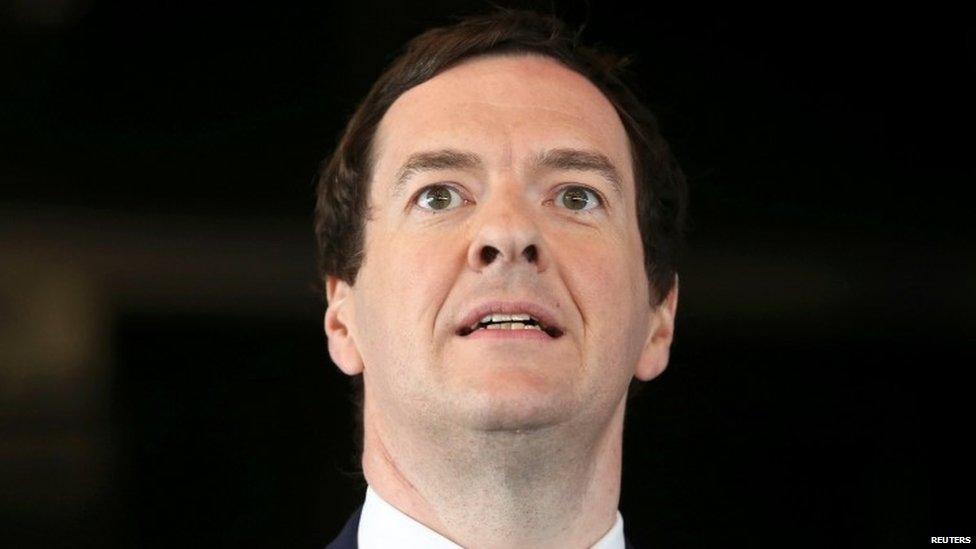

Mr Osborne has said he wants to stand again - but where?

Former Chancellor George Osborne says he wants to stand for election again in 2020 but he faces potential complications as his Cheshire constituency is being abolished.

Under the draft plans, Tatton would be merged into a new Altrincham and Tatton Park seat which could pit Mr Osborne against Graham Brady, chair of the 1922 backbench committee, who is currently MP for Altrincham and Sale West.

The make-up of Nick Clegg's Sheffield Hallam seat is changing significantly, which might make it harder for the Lib Dems to retain, although it is not clear whether the party's former leader will contest it again.

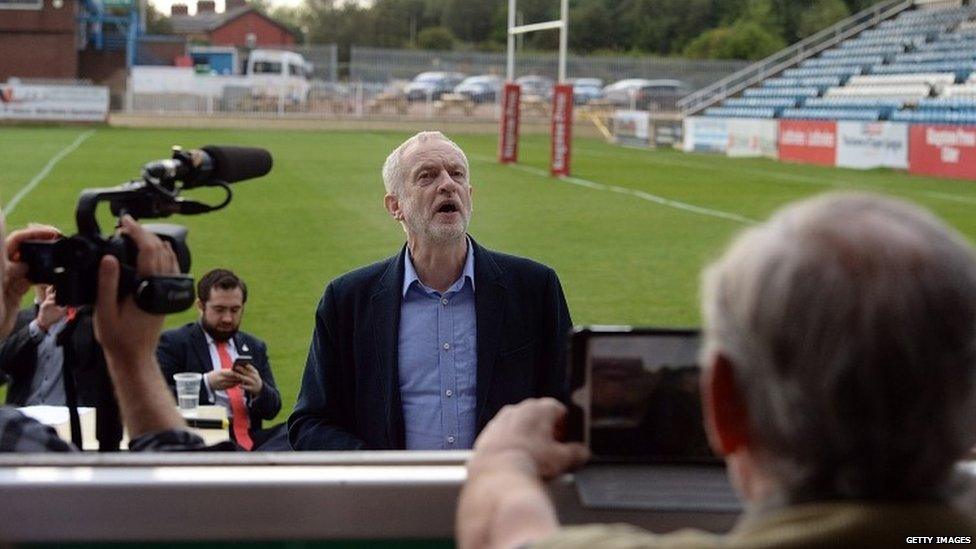

Labour faces a possible game of musical chairs in north-east London with Jeremy Corbyn's Islington North seat effectively merging with Diane Abbott's Hackney North and Stoke Newington to create a new seat of Finsbury Park and Stoke Newington.

While Mr Corbyn will likely contest that seat and Ms Abbott will opt for the new Hackney Central, it would have a knock-on effect for other Labour MPs in the area such as Meg Hillier, Rushanari Ali and Jim Fitzpatrick.

Other MPs whose seats are effectively being abolished or merged with others include ex-Welsh Secretary Stephen Crabb (Preseli Pembrokeshire), Labour leadership contender Owen Smith (Pontypridd), Labour MP Rachel Reeves (Leeds West), Conservative Brexit Secretary David Davis (Haltemprice and Howden) and Labour's Tristram Hunt (Stoke on Trent Central).

One of the most interesting permutations is in Essex where International Development Secretary Priti Patel (Witham) and former culture secretary John Whittingdale could have to compete for the proposed combined seat of Witham and Malden.

However, the likely retirement of a number of long-serving MPs could free up seats and minimise the number of blue-on-blue or red-on-red contests.

A game-changer for Labour and Corbyn?

The boundary review is a subplot to the internal struggle within the Labour party

By 2020, Labour will have been out of power for a decade and anything that is perceived to make their task harder to get back is inevitably a source of angst.

But these are not normal times for the opposition - which is in a state of virtual civil war over Jeremy Corbyn's leadership - and the boundary review is yet another subplot in the internal struggle over the party's future direction.

The current Labour rules, introduced in 2013, state that an MP with a substantial territorial interest in a new constituency may seek selection as a matter of right - a substantial territorial interest is defined as 40% or more of the previous constituency.

MPs who oppose Mr Corbyn are worried that if he is re-elected later this month, members of the local Labour parties who support him could use the review as a pretext to try and change the rules to stop them from standing in 2020.

Although one cannot say with certainty at this stage how many seats each party stands to lose - authoritative figures will not be available until the proposals are finalised in 2018 - guesstimates suggest Labour could "lose" as many as 30 seats.

Allied to potential retirements of sitting MPs at the election, this could usher in major changes to the make-up of Labour politicians in the Commons.

However, there is one important caveat to all this. If an early election is called before 2020, it will be fought on the existing boundaries.

I'm a voter - what does this mean for me?

Proposals for Welsh constituencies will also be announced on Tuesday

Every constituency in the UK is likely to be affected, with many changing name entirely.

By 2020, the aim is that no constituency - except the four "protected" ones - will have less than 71,031 eligible electors or more than 78,507.

There will be 32 fewer seats in England, external than right now, with every region seeing a drop in representation to a proposal total of 501. Under the draft plans, the north-west will be the most affected, its seat numbers falling by seven to 68.

In Scotland, external, seats number will fall by six to 53 while representation in Wales - details of which will also be announced on Tuesday, external - will drop by 11 to 29.

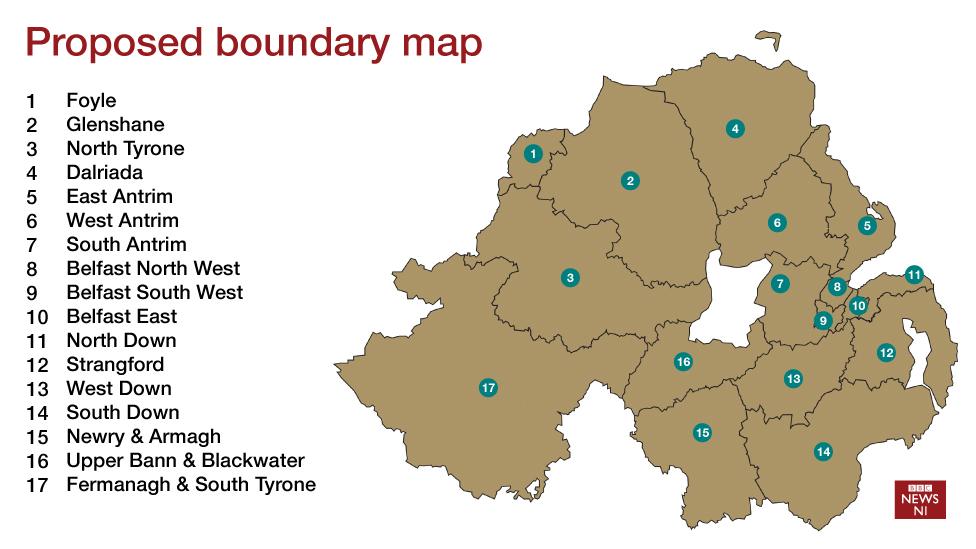

Draft proposals for Northern Ireland, external, which were published last week, will see less change with 17 seats as opposed to 18 now.

The proposals will be available to view on the respective Boundary Commission websites (see below) and deposited in public offices, such as council buildings and public libraries.

Anyone wanting to have their say on the changes can do so at a series of public hearings being held across the UK over the next couple of months.

- Published1 March 2016

- Published6 September 2016

- Published24 February 2016