Labour must stop fighting old battles

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn and Owen Smith respond to the suggestion that neither of them appear able to unite the Labour Party

When I think of Labour's civil war, an image comes to mind of two skeletal generals, sitting at a table on a battlefield, pushing pieces across a board, re-enacting past conflicts, oblivious to the sounds of a real battle all around them.

Or, less extravagantly - two tramps fighting in a ditch over a broken watch, which neither knows how to mend.

Whoever wins Labour's leadership contest, external will have to find a way to fix a couple of problems quite outside their grand, old-fashioned ideological clash.

That's the trouble with civil wars. The grandchildren end up fighting their grandparents' battles, with just as much passion but only a dim echo of relevance.

Of course Owen Smith's pitch, external is that he's a smarter, slicker version of Jeremy Corbyn, but there's no doubt how the forces line up.

The battle for the soul of the left has existed as long as socialist parties themselves. But originally it was about means, not ends - revolution or the parliamentary path, external.

Eventually rejection of revolution encompassed a rejection of its aims as well. Out went state control of the economy and in came an acceptance that social democratic parties would curb capitalism, not replace it - methodism, not Marx, external.

Then Labour leader Neil Kinnock famously denounced the party's Militant Tendency in his 1985 conference speech

Fast forward to Labour in the 1980s and the latest incarnation of the struggle - the campaign to expel the Trotskyist Militant Tendency, external from the Labour Party.

Fast forward even further to Tony Blair's triumph,, external leaving the hard left broken and the sentimental Clause Four scrapped. Only bitter old-fashioned remnants clinging to the wreckage of Marxism remained, only a few people like Mr Corbyn still waving a tattered red banner.

But Mr Blair's New Labour shattered on the rock of Iraq,, external then broke under the weight of 2008's financial crisis., external

Many on the left felt his enthusiastic embrace of military liberal interventionism vindicated their opposition to what they've always called imperialism.

The economic crisis of 2008 left social democratic parties all over the West stranded, their central promise to moderate the market broken.

It made the radical left's attack on what it calls "neoliberalism", external look a lot more pertinent than it had for decades.

But its critique is not - on the whole - matched by equally sharp policy prescriptions. So two discredited ideologies fight out old battles, while the world changes around them at a dizzying pace.

The left is cock-a-hoop to be in charge through a series of accidents and is relishing the battle with the establishment.

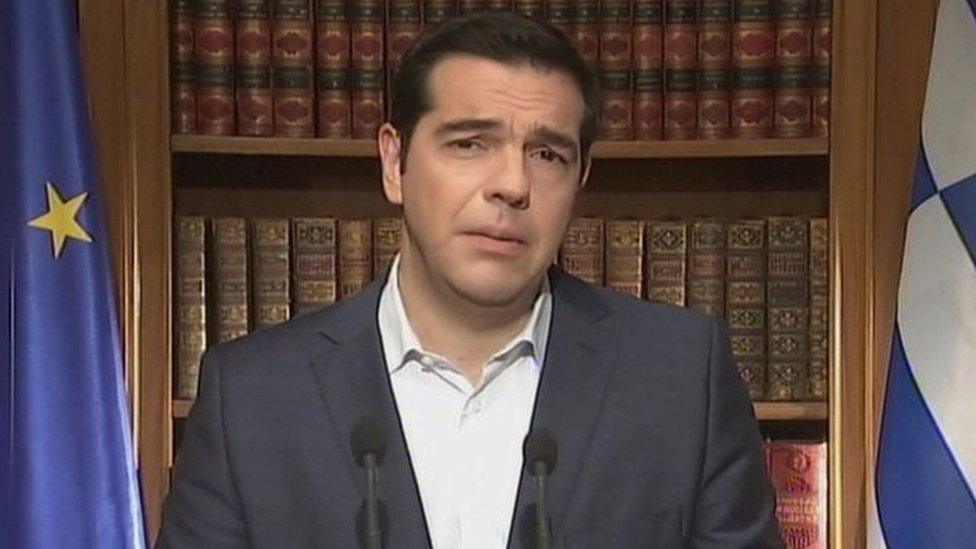

Greece's Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is accused of breaking election promises

You might almost feel this is what these long-term revolutionaries live for - the struggle, not the sometimes bitter and hard-to-swallow fruits of victory. (Ask Greece's Syriza party, external about that.)

The right dismisses the youthful enthusiasts questing for radical change to the way we live as "Trots" or "tankies"., external

One senior MP told me there was no place in the party for the likes of them - to me echoes of the old machine politics of the one-party town hall when people were told they could not join because the Labour Party was "full".

Most shy away from fresh thinking - they just want back the power they had under Gordon Brown and Mr Blair.

If people seem disillusioned with politics as usual, a rerun of the classic 1980s sitcom "Marxist v moderates" may not appeal.

It doesn't make the dispute irrelevant, but it makes their solutions, on both sides, feel piecemeal and outdated.

For Labour faces two big, practical challenges about which neither the left nor the right have much to say.

Both are facets of the politics of identity and nationalism.

The first is what to do about the question at the heart of Brexit - immigration.

Post-Brexit racism: 'There are good Britons and bad Britons'

Many one-time Labour working class supporters - perhaps those who defected to UKIP - voted to leave the EU specifically to curb immigration., external Theresa May obviously thinks she can turn many of these into Conservative voters.

The trouble for Labour is that many in the other half of its grand coalition feel bereft by Brexit, mournful in their belief that their country has taken a nasty turn into a little England, external where foreigners are not welcome.

It will be a tactical question too, if the government fails to meet people's expectations. There's plenty of anecdotal evidence whether from celebrity chefs or Gujarati heritage authors that some voters expected all "European" or "brown" people to be sent packing.

While countering this sort of rhetoric is easy for Labour, the rest is not.

Broadly the party has two choices - educate or accept. Either confront those who dislike immigration and tell them they are wrong, or accept their arguments are right and fight for a particular system of control.

Opting for either will split the party along new fracture lines.

The other problem is Scotland. Whether Labour is led by Mr Smith, Mr Corbyn, Clem Attlee reincarnated or Joe Broon, external, they won't get to be the next Government without winning Scotland back or forming an alliance with the Scottish National Party.

Given that the former is a very long and rocky road indeed, it means the later will be a big question at the next general election.

The Conservatives unveiled the poster after David Cameron called on Labour to rule out a deal with the SNP

There's a fair bit of evidence, external that the possibility of a pact with the SNP did for Ed Miliband - even though he dismissed it - and the Conservative adverts, external showing the then Labour leader in the pocket of then SNP leader Alex Salmond worked.

Acknowledging the possibility of a deal could be deadly both in England and Scotland - dismissing it would suggest a lack of ambition to rule and a lose grasp on reality.

These look to me like unsolvable conundrums, but it would be worth anyone who wants to be Labour leader grappling with these central questions, rather than indulge in rerunning the battles of a past century.

Mark Mardell presents The World This Weekend on BBC Radio 4 on Sundays at 13:00 BST or listen online.

- Published15 September 2016

- Published13 September 2016

- Published11 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016