Labour and the left: A guide to names

- Published

A feature of the fight for control of the Labour Party over the past year has been a fair amount of finger-pointing, with leader Jeremy Corbyn's supporters decried as "Trots" and "anarcho-syndicalists" and his critics branded "Blairites" and "neoliberals". What do all these terms mean?

Socialism

A commitment to socialism has been a central part of the Labour Party since its foundation

While Labour members on different sides of the party might not agree on much, most are happy to call themselves socialists.

It was in Tony Blair's controversial speech to party conference in 1994, and it was in Jeremy Corbyn's speech to conference on Wednesday, when he heralded "21st Century socialism".

Since the idea first came into being in the 19th Century, socialism has taken on many forms, but most versions of it have in common a belief in public rather than private ownership or control of property and natural resources.

Socialists tend to believe everything that people produce is a social product, with everyone who contributes to the production of a good entitled to a share in it.

As socialism first began to move from theory to practice, a division grew up between dictatorships associated with Marxism and democratic socialism as espoused by European political parties.

British socialism took on its own distinct character through the formation of the Labour Party and the trade union movement, which, in the words of Harold Wilson, "owed more to Methodism than to Marxism".

Communism

Vietnam is among the countries where a communist party continues to rule

It has been a matter of debate recently as to whether communists have played a role in the popularity of Jeremy Corbyn - the Communist Party denies getting involved, but many believe other communists have joined the grassroots movement in support of Mr Corbyn.

Communism is usually understood as a process of class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, culminating in revolution, and leading to the establishment of a classless society in which private ownership is no more and the means of production belong to all.

Although its hallmarks also appear in earlier writings, it took a firm shape in the 19th Century in the work of German thinkers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Their ideas underpinned the Russian revolution and a succession of attempts stretching over several continents throughout the 20th Century to put communism into practice, which have led to its being widely discredited as a political system.

How it differs from socialism is a matter of debate, but adherence to the revolutionary socialism of Karl Marx is one hallmark of communism.

Marxism

For some, Jeremy Corbyn represents the resurgence of the Marxist wing of Labour, which fought for the soul of the party in the 1970s and 80s.

Mr Corbyn once told Andrew Marr "we can learn a great deal" from Marx.

Karl Marx's analysis of and prescription for society is a form of socialist thought, but he and Engels defined their philosophy as "scientific socialism", contrasting it with predecessors' "utopian socialism", which they regarded as not paying enough attention to material conditions or how to bring about change.

He saw society as being built around the "material forces of production," - labour and the means of production - and the "relations of production" - the social and political arrangements that regulate them.

Above that, he saw the superstructure - legal and political "forms of social consciousness" that correspond to the economic structure.

History is defined by the struggle between two classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, according to Marx, and the replacement of capitalism with communism can only occur when the proletariat becomes conscious of its oppression and embarks on revolution.

He also thought communism would emerge in advanced economies, although many reinterpretations of his work have tried to transpose his philosophy on to poor, agrarian countries.

Leninism

Lenin's face appears amongst badges at the 2016 Labour conference

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the architect of the Russian revolution, whose image adorns badges on sale at Labour conference this week, overlapped with Marx and Engels but rewrote their ideas to create his own doctrine.

He did not trust that historical events, left to themselves, would lead workers to class consciousness and revolution.

He believed the Communist Party should act as a vanguard, an intellectual elite determined to attain power through any means necessary and to overthrow capitalism once in power.

Other distinctive aspects of his thought include his conviction that the state would "wither away" once communism had been achieved, and that there should be a "proletarian dictatorship" following the seizure of power.

After 1917, however, these aims gave way to an increasingly centralised state and the repression of independent thought, prefiguring the dictatorship of Josef Stalin and permanently shaping how communism in practice would come to be seen.

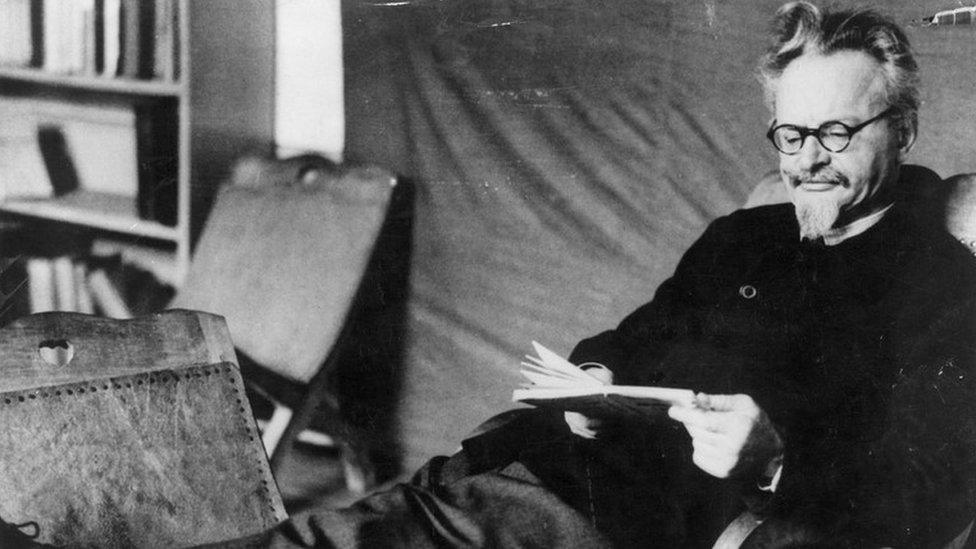

Trotskyism

Leon Trotsky, one of the founders of the Soviet Union, split with Stalin in the 1930s - and was eventually killed in exile by a Stalinist assassin.

The biggest gulf between them was that Stalin believed they could create a socialist society in their own country without a world revolution, whereas Trotsky believed his country could achieve socialism only if the working classes around the world rose up as one to overthrow the ruling classes - the doctrine of "international socialism".

He also thought the Soviet Union had become a dictatorship under Stalin and advocated more democracy in the one-party state.

His philosophy gained traction in parts of Latin America and, at the fringes, in Britain.

He advocated entryism, advising his British followers to form a "secret faction" in the Labour Party to push his revolutionary agenda.

This approach did not begin to bear any real fruit until the 1970s, with the rise of the Militant tendency - and has recently become a live issue again, with deputy Labour leader Tom Watson warning of entryists joining the party to vote for Jeremy Corbyn.

Anarcho-syndicalism

In anarcho-syndicalism, trade unions replace the state altogether

In July, former leader Lord Kinnock told a meeting of his party's MPs, external that Labour believed in parliamentary socialism, not anarcho-syndicalism.

The idea is a variant of anarchism, and revolves around the replacement of the state with trade unions and associated cooperatives (in French, "syndicats").

It had some influence during the Spanish civil war, and the British government was fearful of it taking hold in the 1910s, but it never gained much popularity.

Like other subsets of socialism, it was sent up by Monty Python, in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in a scene where peasants declare themselves part of an anarcho-syndicalist commune in which "we take turns to act as a sort of executive-officer-for-the-week" and "all the decisions of that officer have to be ratified at a special bi-weekly meeting".

Blairism

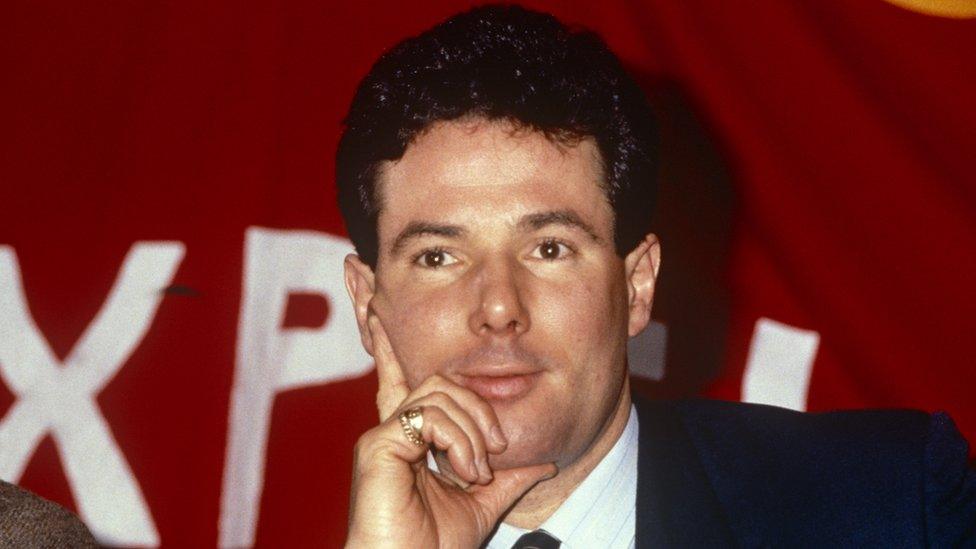

After Tony Blair became leader in 1994, he continued the process of "modernisation" begun by Neil Kinnock, and pushed ahead with abolishing Clause IV of the party constitution.

It ended the supremacy of the party conference, weakened links with the trades unions and killed off cherished old policies, most notably a commitment to public ownership of industry.

This break came with a label of its own, as Mr Blair actively drew a distinction between "old Labour" and "new Labour".

Many observers and party members credited Labour's subsequent electoral success to this innovation, and were happy to describe themselves as Blairites.

But others saw Tony Blair and his supporters as "entryists" - ironic in view of the same accusation currently being made of the left - who were betraying true Labour values.

This is the spirit in which the term "Blairite" has recently been directed at critics of Jeremy Corbyn within Labour.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism defies neat definition, but is sometimes linked to the economists Friedrich von Hayek (pictured) and Milton Friedman

Neoliberalism can be summarised as an economic model that emphasises the value of free market competition, sometimes linked to the economists Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman, although it is difficult to pin down its defining features.

It is commonly associated with a belief in sustained economic growth as the means to achieve human progress and an emphasis on minimal state intervention in economic and social affairs.

It has also been used to refer to the ideology underlying capitalist globalisation - and is most often used as an epithet by anti-capitalists.

Colin Talbot, a professor at Manchester University, recently wrote, external it was such a broad term as to be meaningless and few people ever admitted to being neoliberals - prompting an angry reaction by supporters of Mr Corbyn who thought he was dismissing the threat they believe it poses.

- Published10 August 2016

- Published28 May 2015

- Published25 December 2015

- Published30 July 2015