Talking out: How MPs block Private Members' Bills

- Published

East Dunbartonshire MP John Nicolson tweeted as his bill to pardon men for historical gay sex offences was talked out.

When proposing new laws, ministers can fill the statute books from the relative safety of their positions in government.

But for the average backbench MP, the chance to make laws can seem a distant possibility.

Their best chance comes around once a year, in the form of a random ballot.

The prize? A chance for MPs to promote their pet project in the House of Commons by introducing it as a Private Members' Bill.

Private Members' Bills can be introduced in three different ways. The first are "Ten Minute Rule" bills, where MPs make a speech of no more than 10 minutes to outline their position. Second are presentations to the Commons, where an MP might formally introduce the title of their bill.

The third and most likely to make it onto the statute book are the "Ballot Bills", so-called because MPs take part in a random draw to decide who gets to propose a bill in the Commons.

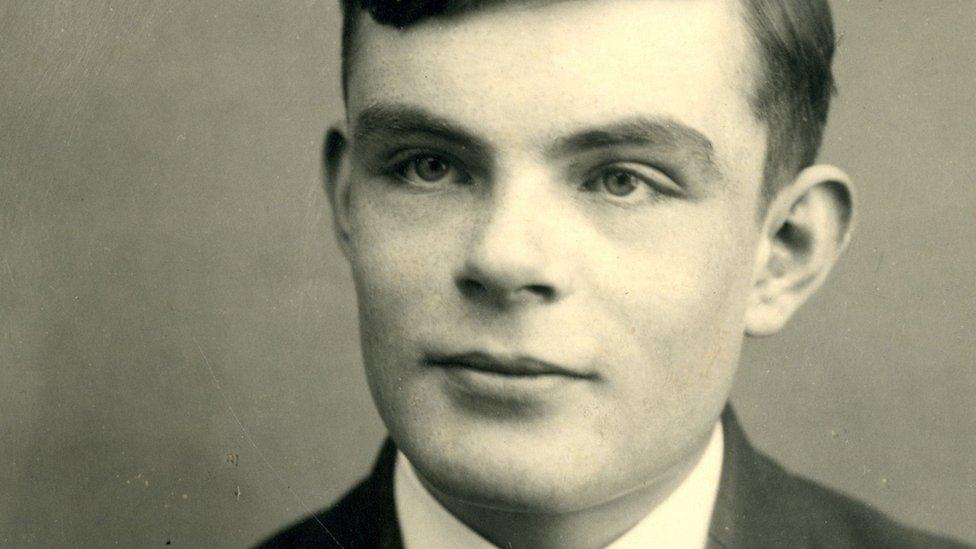

The system has its critics, among them the SNP MP who sponsored the "Turing Bill" to pardon gay men for obsolete sexual offences.

"It is absurd for legislation to be decided by the deputy speaker pulling balls out of a jar. It seems altogether too random," John Nicolson says.

'Fair crack'

If this sounds confusing, it's probably because it is.

In a report, external on Private Members' Bills, the Commons' Procedure Committee called the process "impenetrable" and "enormously damaging to the reputation of the House and to the legislative process".

Chairman of the committee, Broxbourne MP Charles Walker, says: "One thing you have to do in this house is accept failure, but you need to have a fair crack at failure, and I don't think most backbenchers now have a fair crack at failure."

Even if an MP is lucky enough to propose their Private Members' Bill to the Commons, it is far from guaranteed that it will become law.

Justice Minister Sam Gyimah heckled by MPs during Turing Bill debate

Opposing MPs can stop these sorts of bills progressing by "filibustering" or "talking them out" during debates held on 13 Fridays throughout the year - a process the Procedure Committee report describes as "speaking at inordinate length on the bill to ensure that the debate cannot conclude" before the set time limit.

Mr Nicolson's Private Members' Bill, the Sexual Offences (Pardons) Bill, fell after a government minister used up the time allotted for debating it by speaking for 25 minutes.

Speaking in May, Deputy Speaker Lindsay Hoyle explained the updated way of choosing private members' bills.

There were cries of "shame" and "shameful" from some MPs as Justice Minister Sam Gyimah's speech brought the debate to a close.

Speaking to the BBC Mr Nicolson said: "I think voters consider filibustering to be wrong. And I agree with them.

"Filibustering is archaic, and often used to frustrate the Private Members' Bill process. If a minister doesn't talk out a bill, a hard core of obstructionist MPs often do it, talking nonsensically for lengthy periods until the time allocated for the bill is over."

Mr Gyimah defended his opposition to Mr Nicolson's bill, saying "I understand and support the intentions behind Mr Nicolson's bill, however I worry that he has not fully thought through the consequences."

'Different opinions'

Conservative MP Philip Davies, a regular attendee of Friday debates on Private Members' Bills, mounted a passionate defence of talking out.

Speaking to a Procedure Committee evidence session Mr Davies said: "I support a bill by not speaking at all, and stop a bad bill from going forward by running out of time.

Philip Davies says talking out is the only mechanism for blocking bad bills

"If the purpose of me contributing to the debate is to try to stop bills that I think are bad, this is the mechanism that I have to use, under the rules," he continued.

"If there was another mechanism of blocking them that didn't involve me speaking in the debate, the chances are that I would use that mechanism and therefore nobody would hear another point of view. You would only hear one side."

Mr Davies concluded: "When we have a debate, whether people like the outcome or not, at least people get to hear that there is a different opinion on a particular bill."

Green Party co-leader Caroline Lucas had a similar experience of a bill being talked out in 2015.

Her "NHS Reinstatement" bill ran out of time after MPs spent four-and-a-half hours debating the two-clause Foreign National Offenders (Exclusion from the UK) bill.

'Turn-off'

Ms Lucas told the Procedure Committee the bill was one that "certain MPs have 'on the shelf' for the purpose of clogging up Private Members' Bill time on Fridays".

The Brighton Pavilion MP told the BBC: "What really turns the public off politics is witnessing the childish way some MPs speak for a huge amount of time in order to 'talk out' bills and prevent them from being concluded and voted on."

Debates on private members bills are often sparsely attended

While talking out has many opponents, there are ways of clamping down on the practice that already exist.

In its recommendations for changes to the Private Members' Bill process, the Procedure Committee suggested that the Speaker and his deputies overseeing debates on them should make greater use of their existing ability to impose time limits on speeches.

Equally, an MP sponsoring a Private Members' Bill can attempt to close a debate before it runs out of time. The problem is that to do so 100 MPs have to be present in the chamber - a requirement the committee's report called a "a formidable hurdle" to overcome on Fridays, when many MPs have already returned to their constituencies.

In the end, opponents of talking out may be disappointed, because the Procedure Committee stopped short of calling for a ban.

Warning against applying more rules to Commons debates, the committee instead suggested limiting opportunities to indulge in the practice.

"The more rules there are, the greater the opportunities to game them," it said.

- Published21 October 2016

- Published27 May 2016

- Published6 March 2015