The rise of the word Brexit

- Published

Use of the word surged around the EU referendum in June

It was the political word of 2016 - even before being repeatedly used by Donald Trump during his successful US presidential campaign. But Brexit was barely heard last time America elected a president in 2012. Here's the story of its rise to prominence.

Who coined the phrase?

The Oxford English Dictionary awarded this honour to Peter Wilding when it added Brexit to its volumes recently.

Mr Wilding is the founder and director of the British Influence think tank - and campaigned for the UK to Remain in the EU in June's referendum.

He wrote about "Brexit" in May 2012, eight months before the then Prime Minister David Cameron had announced he would be holding a referendum.

"Unless a clear view is pushed that Britain must lead in Europe at the very least to achieve the completion of the single market then the portmanteau for Greek euro exit might be followed by another sad word, Brexit," he predicted, external.

Reflecting on being first to use the term, he says: "I had no idea but got a phonecall a couple of months ago from the Oxford English Dictionary.

"It certainly gives one the moral authority to say what it means."

Donald Trump often compared his presidential campaign with Brexit

Mr Wilding took his inspiration from Grexit, the term used for Greece's possible exit from the eurozone.

"In January and February 2012 it was all about the Greek crisis," he said,

"It didn't take a great leap of faith to replace the G with a B so that's how it came about.

"It's one of those odd things that crops up in life, I had forgotten all about it, so when I was told I found it amusing."

Brexit not Brixit

It could have all been (slightly) different.

Brexit was far from set in stone, and faced early competition with an alternative version featuring the following month in an Economist article, external predicting that "a Brixit looms for several reasons".

In August 2012, investment bank Nomura made waves when it warned the City in a report that a "Brixit" was "increasingly likely", while the same term was used in a Daily Mail column, external urging: "Bring on the 'Brixit'."

But Brexit prevailed, although it was another three years before its use really took off.

Any linguistic merit?

Not really, according to Professor David Crystal, one of the world's foremost experts on language.

"From a linguistic point of view it's just another word," he told the BBC.

"The only interesting feature is the way the 'exit' part has become productive, acting like a suffix (Grexit, Frexit, etc), which is unusual.

"New suffixes don't arise very often, a previous example was '-gate' after Watergate."

According to Macmillan Dictionary, it "reflects a growing trend in recent years of coining a catchy new expression to appealingly characterise a topical scenario".

Cashing in

Brexit may not be confined to politics for much longer, with 18 trademark applications featuring the term lodged so far.

They include "English Brexit tea" by a German company in the days after the referendum.

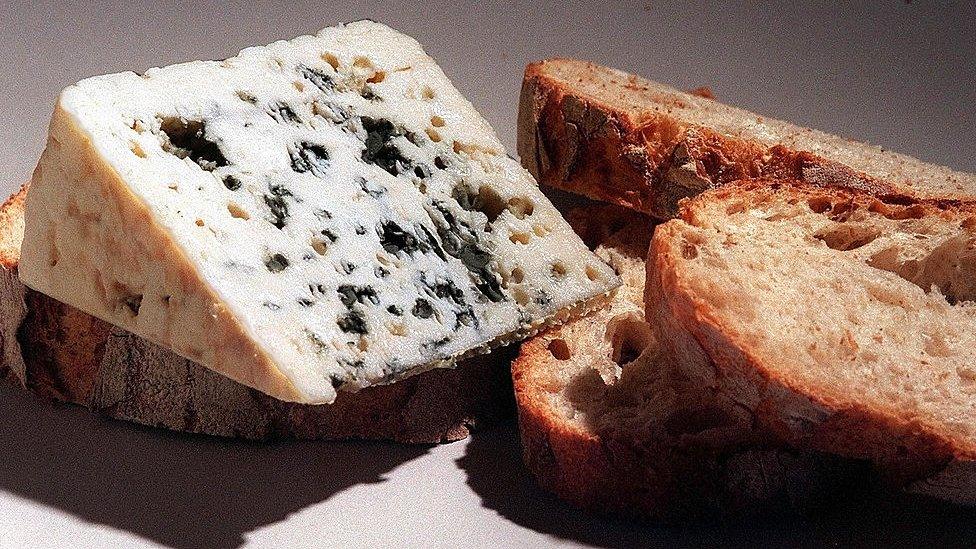

There's also Brexit Blue cheese, Brexit biscuits, Brexit energy drinks and Brexit bread - while Brexit the Musical and the Brexit board game have also been snapped up.

There have also been 36 companies registered including the word in their name, almost all since the referendum.

'The word on everyone's lips'

A glance at the Google searches, external on Brexit shows how use of the word rocketed around the EU referendum.

Similar trends were recorded by BBC Monitoring, which looks at the international media, both in Europe and around the world.

Collins Dictionary, which recently named Brexit as its word of the year, said its use had increased by 3,400% this year according to its monitoring systems.

"It's such a huge increase in usage of one particular word," said Collins editor Mary O'Neill.

"It was talked about a bit last year but nothing like what it was like in 2016.

"It's really amazing how it has gone from virtually nothing to the word on everyone's lips."