UK aid money: Generosity or wasted spending?

- Published

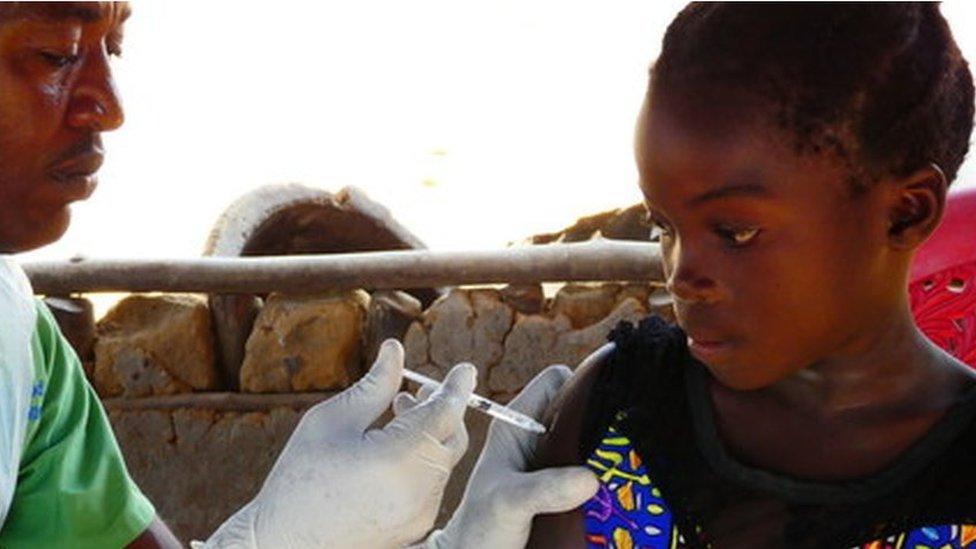

Ugandan girls are being given HPV vaccine to protect them from cervical cancer

A class of Ugandan schoolgirls lines up under a tree. They are waiting to receive the HPV vaccine, which will protect them from cervical cancer.

The project is run by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance which in turn has received a significant amount of funding from British taxpayers.

With a budget of more than £12bn, the Department for International Development is an arm of government with spending power that is likely to keep growing.

The UK has passed a bill that enshrines in law its commitment to spend 0.7% of the country's gross national income on aid every year.

But that commitment, while welcomed by some as a mark of British generosity, is dismissed by others as a licence to spend money on projects of dubious value.

Soft power?

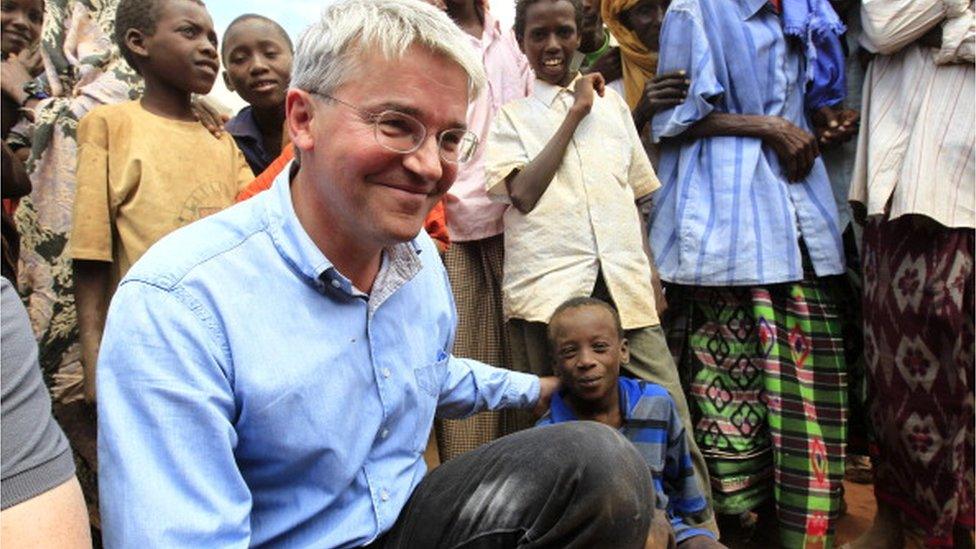

The Conservative MP and former international development secretary Andrew Mitchell is a staunch defender.

"There is massive need, we can see it in the world today, huge discrepancies of opportunity, deep, deep poverty," he says.

"The British development budget is addressing these colossal discrepancies, and it does so extremely effectively."

Former International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell is a staunch supporter of the British development budget

The current Secretary of State for International Development, Priti Patel, once advocated scrapping the department she now leads.

And since taking up the role, she has stressed that it is in Britain's "national interest" to invest across the world, to alleviate poverty and suffering.

Speaking at the Conservative Party conference in September, Ms Patel said: "Our aid programme forms a crucial part of Britain's soft power around the world.

"When people in refugee camps or remote communities see the Union Jack displayed proudly on our emergency supplies, they know they have a friend and an ally in Britain."

Priti Patel says the Union flag shows people they have an ally in Britain

Some believe that world view may be given extra impetus by the need to forge trade deals, in the wake of Brexit.

But Kirsty McNeill, executive director of policy and campaigns at Save the Children, says we should give because we can.

"If I saw a drowning man in the Thames on the way home tonight and I saved him, it may well do wonders for my reputation, but that's not why I do it - I do it because if you can save a life, you should save a life," she says.

The UK government has pledged £8m to help reduce food shortages in Malawi

Jonathan Foreman, author of Aiding and Abetting: Foreign Aid Failures and the 0.7% Deception, takes a far more sceptical view.

He says that far from being good for the national image, if money is handed over to people in a country who are known to be powerful and corrupt, it can be very damaging.

"People in those countries think you must have known it was a corrupt country, you must have known that school was not going to be built, and then they think you are in league with the people whose mis-governance is making this country such an impoverished place," he says.

There are other pitfalls too.

Owen Barder, from the Centre for Global Development think tank, says: "The US and in the past the EU shipped a lot of food aid from our own countries.

"It was in the national interest to buy it from our farmers and ship it there, but it was much more expensive.

"Our aid saved many fewer lives, and we drove local farmers and local suppliers out of business."

Given that "promoting global prosperity" is among Dfid's priorities, putting local traders out of business is not part of the plan.

Sending food from the UK to other countries put local suppliers out of business

But Michela Wrong, the author of It's our turn to Eat - which looks at corruption in Kenya, believes there is another problem with the UK's choice of aid partners.

She points to countries such as Rwanda, Ethiopia and Uganda, which, she says, are not particularly good at promoting democracy and human rights but are successful at building schools and improving maternal health.

"Is that model really sustainable?" she asks.

Mr Mitchell accepts this is not ideal but says the aid relationship is not with the governments but with the people.

And if you withdraw the aid, "you're taking girls out of school, or stopping farmers accruing the knowledge to be able to feed themselves and their locality".

One of Ms Patel's priorities is to deliver value for money in aid - but some in the aid world argue it is not always easy to measure outcomes.

You may be able to count the number of children that have been given access to a school, but how can you assess the quality of the education they have received?

Priti Patel wants more accountability with international aid money

Many of these arguments have been thrashed out in the development world for decades, but Mr Barder says the problems traditionally linked to aid should have an even bigger resonance now because they try to address shared problems.

"Like climate change, which we have to tackle together, problems of conflict and insecurity, problems of global health, of inequality and those requiring shared policy solutions, aid is part of the solution," says Mr Barder.

"The votes we have seen on Brexit and Donald Trump are the people saying to the politicians, 'You are not addressing these problems fast enough and in the way we need.'"

But as electorates reject global trade deals and multinational groupings such as the EU, it may be more difficult than ever to persuade countries to work together.

At the same time, the problems of poverty and inequality are being fuelled by conflict, corruption and political instability.

In Uganda, the plan is to end the support for the vaccination programme by 2020, when it is hoped the country will be wealthier.

But for the moment, British taxpayers will continue to help protect the health of Ugandan children.

- Published24 October 2016

- Published25 October 2016