Populism: Pantomime politics or the public fighting back?

- Published

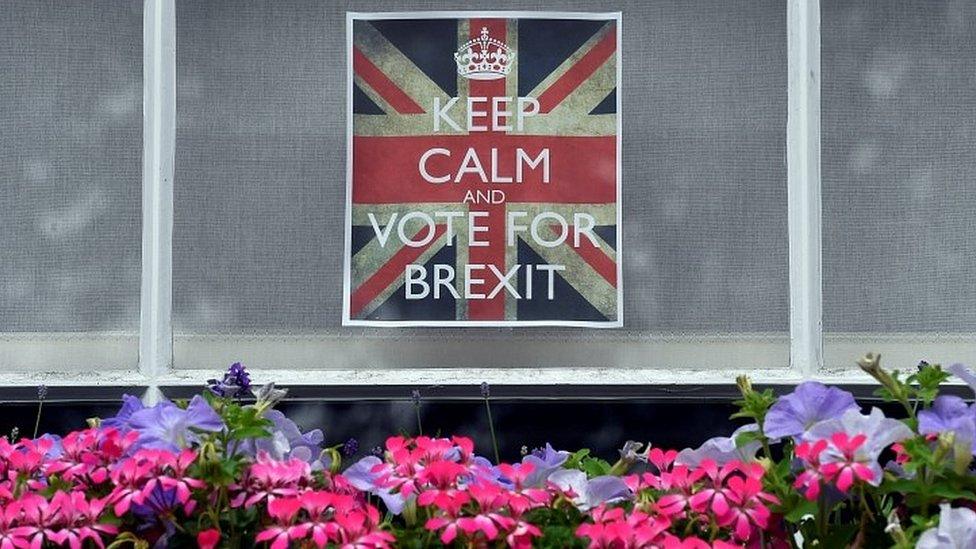

Was the Brexit vote a popular uprising against the political and business elite?

The man who was prime minister last Christmas and isn't this Christmas thinks he knows why.

"I stand here as a great optimist about how we can combat populism. It may seem odd that I am so optimistic, because after all the rise of populism cost me my job."

So said David Cameron recently, on the lecture circuit for the defeated, at DePauw University in Indiana in the United States.

The man who is president of the United States this Christmas and won't be for much longer has opined on the subject too.

"This whole issue of populism. Maybe somebody can pull up in a dictionary the phrase populism. But I am not prepared to concede the notion that some of the rhetoric that has been popping up is populist," Barack Obama said recently.

OK then, Mr President, let's take you up on that dictionary idea.

"There is no definition of populism. It is like liberalism or conservatism. It varies from continent to continent and century to century," John Judis, the author of the book called The Populist Explosion told BBC Radio 4's The World at One.

But, he added: "Populism is based on a dichotomy, on a differentiation between the people and the elite."

'Pantomime campaign'

So, can the word "populist" be usefully attached to Jeremy Corbyn, Donald Trump and Brexit?

"The strategy that we adopted was really quite a simple one because we realised that to get attention, similar to Trump, we had to be outrageous," recalled Andy Wigmore, the director of communications for Leave.EU, a group he described as the "provisional wing" of the broader Leave movement, during the EU referendum campaign.

Can Labour and other parties of the left harness these new political forces?

"There was an element of pantomime to our approach. The more outrageous we were, the more attention we discovered we got. The more attention we discovered we got, the more outrageous we were. That was the foundation of our campaign."

The Trump campaign in America was their template. Their critics describe both as crude, irresponsible and, yes, populist.

But Andy Wigmore said that was unfair: it was about engaging those who had, until then, given up on politics.

"They were the two and a half million people who had never voted before, very much in Labour strongholds. And that is what we concentrated on. So were we irresponsible to put messages out to them? No.

"We had to use every weapon we could, against an establishment that was attacking everything that was said and everyone who was saying it. Nigel Farage being a classic example."

Sharing power

So is there a parallel here, however unlikely, between Mr Farage and the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn?

"There is the common theme of being against the establishment and challenging an establishment that has become completely corrupt and out of touch with the people," Hilary Wainwright, the co-Editor of the socialist, feminist and green magazine Red Pepper said.

"Nevertheless, Jeremy's whole ethics and political demeanour is one of him, a politician, believing in the people. He is actually not simply giving a voice to the people but also attempting to build a politics that shares power with the people. I don't think that is yet built into the understanding of populism."

If Donald Trump moves to the centre once in power, what will his supporters think?

The success of those who define themselves against the so-called "establishment" arguably creates a bigger challenge for them having won, because of the scale of what their supporters expect them to achieve.

But, looking at President-Elect Trump, John Judis has noticed a partial shift in emphasis.

"What Trump has done is, he's definitely shed some of his populist rhetoric. The idea that he was going to "drain the swamp" of all of these fat cats who were controlling Washington.

"He's ended up with an administration filled with Wall Street people and billionaires. But in terms of some of his demands about jobs no longer being shipped overseas, bad trade deals, changing the relationship with China, he is going to try to do them. When a populist takes power, that doesn't necessarily mean they are going to fail at their task."

'It's democracy'

Let's conclude by returning to that fuzzy concept of populism.

Douglas Murray, an associate editor at The Spectator magazine, says the word is so debased in reality it only conveys one impression.

"When I see the term 'populism' used, I know the author is referring to a movement the author he or she doesn't like. That is what it does. It signals to the listener that the thing they are deprecating is to be deprecated."

But, he argues, whether you think the term has any value or not, what it is attempting to describe does matter and must be celebrated.

"We had in Britain, for years, a mounting problem about this issue about our relationship with the European Union.

"I am amazed that so many people have chosen to interpret the most legitimate expression of dislike that you can do - ie voting - and interpreting that as some awful, rabble-like, unwashed monstrosity. It is the only thing we have to stop something, far, far worse."

- Published25 December 2016