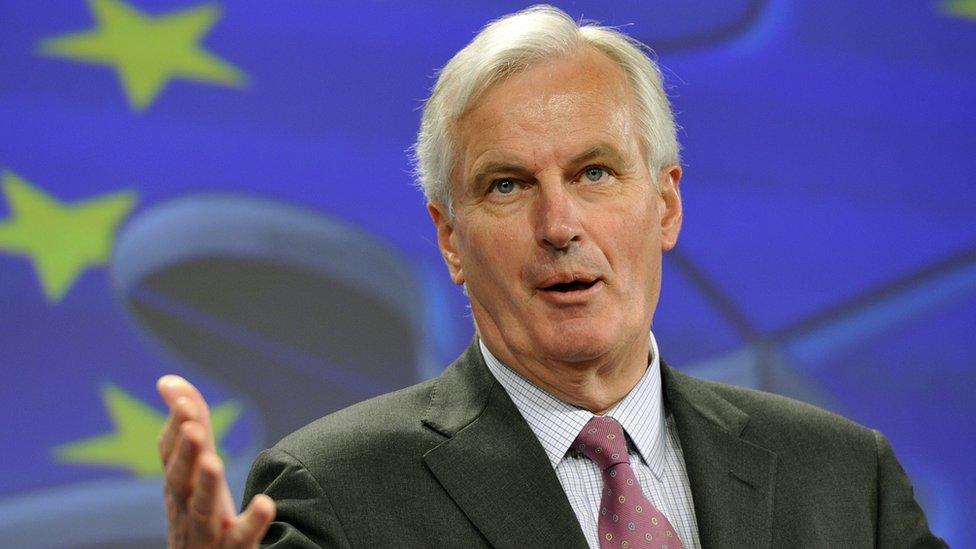

Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier: Hardliner or deal maker?

- Published

Watch Nicholas Watt's in-depth profile of the EU's chief Brexit negotiator

Just over half a century ago Britain's place as an estranged member of the European family was cemented by a Frenchman when President Charles De Gaulle vetoed the UK's attempts to join the EEC.

Britain eventually joined the club. Now, as it leaves the EU, a political descendant of the wartime Free French leader will play the decisive role in deciding the nature of the UK's future relationship with the EU.

Michel Barnier, the former French foreign minister who is the EU's chief negotiator on Brexit, has spent the last few months on a Grand Tour of Europe to agree a common front once the formal talks start in the spring.

So just who is Michel Barnier? Is he a European federalist out to punish Britain or is he more of a deal maker who will work hard to avoid a so-called train crash Brexit in which the UK falls out of the EU in a disorderly fashion?

'Ski instructor'

The Barnier story begins in his backyard in the French Alps where he organised the 1992 Winter Olympic Games - one of his proudest achievements.

To the Paris elite the Olympics marked Barnier out as something of provincial figure who is guilty of a grave offence for a senior French public official; he failed to attend the elite Ecole nationale d'administration.

Baroness Bowles, the former Liberal Democrat MEP who knows Barnier from her time as chair of the European Parliament's Economic and Monetary Affairs committee, says he was known as the "ski instructor".

Michel Barnier and his wife Isabelle

Lord Patten of Barnes, the former Tory chairman, who knew Barnier from his time as France's junior European commissioner, did not see him as a top flight politician.

"He's not a joke. He's not a second rater - he'd be perfectly plausible, given our national differences, in a British cabinet in a sort of job like minister of transport," he said.

"I'm not being too condescending but I don't think he'd be home secretary or foreign secretary."

As someone who was shunned by the gilded elite of Paris, Barnier potentially has common ground with his UK counterpart, David Davis, whose friends feel he was patronised by former PM David Cameron's circle.

But friends of Barnier suggest they were hardly soulmates when they both served as Europe minister because Davis opposed the EU's social chapter.

As Europe minister, Barnier showed that he hailed from the Gaullist tradition in France which is suspicious of the Anglo-Saxon world view.

But he is no diehard Gaullist and bears no ill will to Britain, according to an old ally.

Pragmatic figure

Michel Dantin, who is now an MEP, told Newsnight: "Michel Barnier is a Gaullist, a social Gaullist. His idea of Europe is a Europe of nations and not a federation.

"I think that in the forthcoming negotiations he will respect the British nation because he is aware of history and his approach is to respect others."

Barnier's Brussels breakthrough came in 2010 when he landed one of the biggest jobs in the European Commission - as internal market commissioner.

This gave him oversight of the City of London, prompting howls of outrage that a Frenchman would undermine a key part of the UK economy.

Mr Barnier with Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem

Lord King of Lothbury, the former governor of the Bank of England, raised his voice in a meeting with Barnier in his office in 2011 after he put forward proposals to regulate banks.

King told Barnier that his ideas on the amount of equity finance banks should issue and the amount of liquidity the banks should hold ran were inconsistent with the proposals of the Basel committee.

Bank sources said that King did not believe Barnier was hostile to the City; he was simply wedded to the idea of pan-European regulation.

Mark Hoban, City minister at the time, saw a more pragmatic figure who underwent a learning curve.

"Certainly I found him, at the beginnings of my dealings with him in the aftermath of the crisis, very keen to talk about the failure of Anglo Saxon capitalism because he knew that played well in continental Europe," he said.

"Two years later, as I was leaving the Treasury, [I found him] more attuned to jobs and growth."

Red lines

Barnier's track record in Brussels made him the natural choice as the chief Brexit negotiator.

Nigel Farage, the former UKIP leader, believes Barnier will be guided entirely by maintaining the sanctity of the European project.

"Crucially he's of the project. He's a true believer in the religion of building a united states of Europe and so he's the man they're going to trust."

Jonathan Faull, who has just retired after 38 years of service in the European Commission where he worked with Barnier, says he will not set out to punish Britain. But he will have red lines.

"Mr Barnier will want to be constructive I have no doubt," said Faull.

"He will want to secure the best possible deal for the 27 states of the EU, a deal which maintains their integrity and their fundamental principles governing their internal market."

In private, Davis believes there are two Michel Barniers. One is the hardliner who vented frustration over Britain's approach at an informal meeting last year.

But the Brexit secretary is expecting to meet a flexible deal maker once the formal negotiations are under way this spring.

Dantin, one of Barnier's oldest political allies, warns Davis to work hard on building a relationship with him.

"If we want the negotiations to succeed it is necessary to have confidence between the two main negotiators," he said.

"If the negotiations go wrong the EU will not have much to lose but the UK will have much to lose. That is because the UK is effectively the supplicant."

The future of Britain's scratchy relationship with the EU will, in the initial negotiations, rest in the hands of two political outsiders.

Perhaps they will find common ground over their shared love of outdoors sport, though the silver haired and suave Frenchman would probably never be seen dead hiking across mountains in the style of his British counterpart.

Nicholas Watt, external is political editor for BBC Newsnight

- Published5 January 2017

- Published3 October 2016

- Published27 July 2016