Local voting figures shed new light on EU referendum

- Published

- comments

The BBC has obtained a more localised breakdown of votes from nearly half of the local authorities which counted EU referendum ballots last June.

This information provides much greater depth and detail in explaining the pattern of how the UK voted. The key findings are:

The data confirms previous indications that local results were strongly associated with the educational attainment of voters - populations with lower qualifications were significantly more likely to vote Leave. (The data for this analysis comes from one in nine wards)

The level of education had a higher correlation with the voting pattern than any other major demographic measure from the census

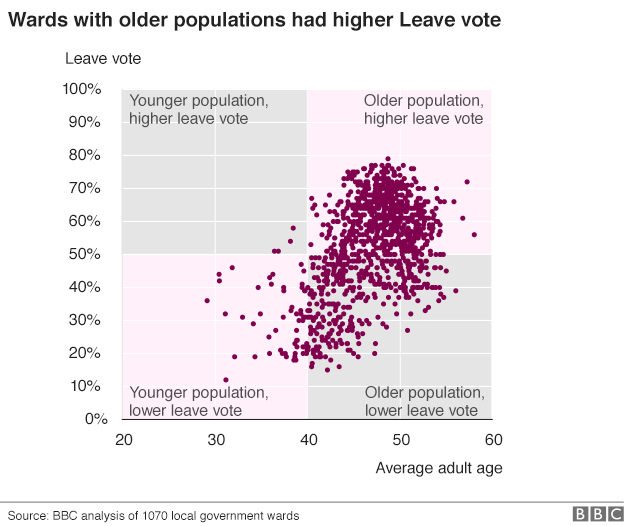

The age of voters was also important, with older electorates more likely to choose Leave

Ethnicity was crucial in some places, with ethnic minority areas generally more likely to back Remain. However this varied, and in parts of London some Asian populations were more likely to support Leave

The combination of education, age and ethnicity accounts for the large majority of the variation in votes between different places

Across the country and in many council districts we can point out stark contrasts between localities which most favoured Leave or Remain

There was a broad pattern in several urban areas of deprived, predominantly white, housing estates towards the urban periphery voting Leave, while inner cities with high numbers of ethnic minorities and/or students voted Remain

Around 270 locations can be identified where the local outcome was in the opposite direction to the broader official counting area, including parts of Scotland which backed Leave and a Cornwall constituency which voted Remain

Postal voters appear narrowly more likely to have backed Remain than those who voted in a polling station

The national picture

Education

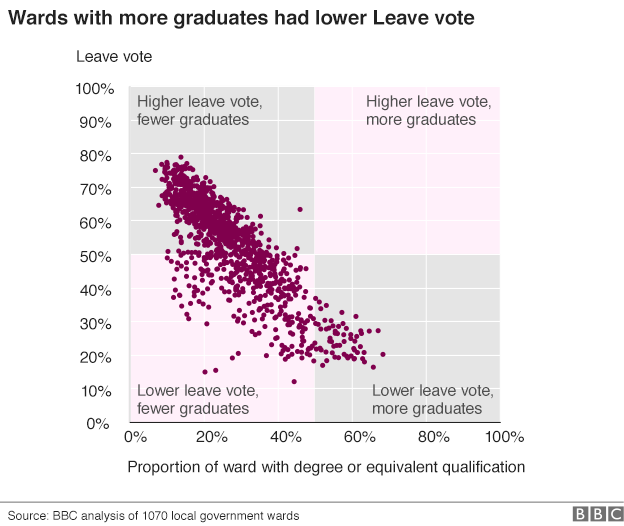

A statistical analysis of the data obtained for over a thousand individual local government wards confirms how the strength of the local Leave vote was strongly associated with lower educational qualifications.

Wards where the population had fewer qualifications tended to have a higher Leave vote, as shown in the chart. If the proportion of the local electorate with a degree or similar qualification was one percentage point lower, then on average the leave vote was higher by nearly one percentage point.

Using ward-level data means we can compare voting figures in this way to the local demographic information collected in the 2011 census. Of the main census statistics, this is the one with the greatest association with how people voted.

In statistical terms the level of educational qualifications explains about two-thirds of the variation in the results between different wards.

The correlation is strong, whether based on assessing graduate and equivalent qualifications or lower-level ones.

This ward-by-ward analysis covers 1,070 individual wards in England and Wales whose boundaries had not changed since the 2011 census, about one in nine of the UK's wards. We had very little ward-level data from Scotland, and none from Northern Ireland.

It should be noted, however, that many ward counts also included some postal votes from across the counting area, and therefore some variation between wards will have been masked by the random allocation of postal votes for counting. This makes the results less accurate geographically, but we can still use the information to explore broad national and local patterns.

Age

Adding age as a second factor significantly helps to further explain voting patterns. Older populations were more likely to vote Leave. Education and age combined account for nearly 80% of the voting variation between wards.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is a smaller factor, but one which also contributed to the results. Adding that in means that now 83% of the variation in the vote between wards is explained. White populations were generally more pro-Leave, and ethnic minorities less so. However, there were some interesting differences between London and elsewhere.

The ethnic dimension is particularly interesting when examining the outliers on the graph that compares the Leave vote to levels of education.

Some wards in Birmingham illustrate the pattern of ethnic minority populations being more likely to support Remain.

There are numerous wards towards the bottom left of the graph where electorates with lower educational qualifications nevertheless produced low Leave and high Remain votes. This is where the link between low qualifications and Leave voting breaks down.

It turns out that these exceptional wards have high ethnic minority populations, particularly in Birmingham and Haringey in north London.

In contrast, there are virtually no dramatic outliers on the other side of the line, where comparatively highly educated populations voted Leave. Only one point on the graph stands out - this is Osterley and Spring Grove in Hounslow, west London, a mainly ethnic minority ward which had a Leave vote of 63%. While this figure does include some postal votes, they are not nearly enough to explain away this unusual outcome.

In fact, in Ealing and Hounslow, west London boroughs with many voters of Asian origin, the ethnic correlation was in the other direction to the national picture: a higher number of Asian voters was associated with a higher Leave vote.

Overview

This powerful link to educational attainment could stem from the lower qualified tending to feel less confident about their prospects and ability to compete for work in a competitive globalised economy with high levels of migration.

On the other hand some commentators, external see it as primarily reflecting a "culture war" or "values conflict", rather than issues of economics and inequality. Research shows that non-graduates tend to take less liberal positions than graduates on a range of social issues from immigration and multi-culturalism to the death penalty.

The former campaign director of Vote Leave, Dominic Cummings, argues, external that the better educated are more prone to holding irrational political opinions because they are more driven by fashion and a group mentality.

Of course this assessment does not imply that Leave voters were almost all poorly educated and old, and Remain voters well educated and young. The Leave side obviously attracted support from many middle class professionals, graduates and younger people. Otherwise it couldn't have won.

While there was undoubtedly a lot of voting which cut across these criteria, the point of this analysis is to explore how different social groups most probably voted - and it is clear that education, age and ethnicity were crucial influences.

After these three key factors are taken into account, adding in further demographic measures from the census does little to increase the explanation of UK-wide voting patterns.

However, this does not reflect the distinctively more pro-Remain voting in Scotland, since we are short of Scottish data at this geographical level. It is clear as well that in a few specific locations high student numbers were also very relevant.

To a certain extent, using the level of educational qualifications as a measure combines both class and age factors, with working class and older adults both tending to be less well qualified.

But the association between education and the voting results is stronger than the association between social or occupational class and the results. This is still true after taking the age of the local population into account.

This suggests that voters with lower qualifications were more likely to back Leave than the better qualified, even when they were in the same social or occupational class.

The existence of a significant connection between Leave voting and lower educational qualifications had already been suggested, external by analysis of the published referendum results from the official counting areas.

The data we have obtained strengthens this conclusion, because voting patterns can now be compared to social statistics from the 2011 census at a much more detailed geographical level than by the earlier studies.

The BBC analysis is also consistent with opinion polling (for example, from Lord Ashcroft, external, Ipsos Mori , externaland YouGov, external) that tried to identify the characteristics of Leave and Remain voters.

Local patterns

The data we have collected can be used to illustrate the sort of places where the Leave and Remain camps did particularly well: it is hard to imagine a more glaring social contrast than that between the deprived, poorly educated housing estates of Brambles and Thorntree in Middlesbrough, and the privileged elite colleges of Market ward in central Cambridge.

It is important to bear in mind, however, that most of the voting figures mentioned below also include some postal votes, so they should be treated as approximate rather than precise. It is also important to note that the examples are limited to the places for which we were able to obtain localised information, which was only a minority of areas. The rest of the country may well contain even starker instances.

Leave strongholds

Of the 1,283 individual wards for which we have data, the highest Leave vote was 82.5% in Brambles and Thorntree, a section of east Middlesbrough with many social problems. Ward boundaries have changed since the 2011 census, but in that survey the Thorntree part of the area had the lowest proportion of people with a degree or similar qualification of anywhere in England and Wales, at only 5%. And according to Middlesbrough council, external, the figure for the current Brambles and Thorntree ward is even lower, at just 4%.

Second highest was 80.3% in Waterlees Village, a poor locality within Wisbech, Cambridgeshire. This area has seen a major influx of East European migrants who have been doing low-paid work in nearby food processing factories and farms, with tensions between them and British residents.

Other wards with available data which had the strongest Leave votes were congregated in Middlesbrough, Canvey Island in Essex, Skegness in coastal Lincolnshire, and Havering in east London.

Remain strongholds

The highest Remain vote was 87.8% in Market ward in central Cambridge, an area with numerous colleges and a high student population, in a city which was strongly pro-Remain.

This was followed by Ashley ward (85.6%) in central Bristol, a district featuring ethnic diversity, gentrification and alternative culture.

Next highest was Northumberland Park (85.0%) in Haringey, north London, which has a substantial black population.

Other wards with available data which had the strongest Remain votes were generally located in Cambridge, Bristol and the multi-ethnic London boroughs of Haringey and Lambeth.

In the middle

The count for Ashburton in Croydon, south London, split 50-50 exactly, with both Leave and Remain getting 3,885 votes, but that did include some postal ballots.

Nationally representative

As for being nearest to the overall result, the combined count of Tulketh and University, neighbouring wards near the centre of Preston, was 51.92% for leave, very close to the UK wide figure of 51.89%. The individual ward of Barnwood in Gloucester had Leave at 51.94%. Both figures however contain some postal votes.

Given that a few councils provided even more detailed data down to the level of polling districts, it is possible to identify some very small localities that were nicely representative of the national picture.

The 527 voters in the neighbouring districts of Kirk Langley and Mackworth in Amber Valley in Derbyshire, whose two ballot boxes were counted together, produced a leave proportion of 51.99%. And this figure is not contaminated by any postal votes.

So journalists (or anyone else for that matter) who seek a microcosm of the UK should perhaps visit the Mundy Arms pub, external in Mackworth, the location for that district's polling station.

Similarly, the 427 voters in the combined neighbouring polling districts of Chiddingstone Hoath and Hever Four Elms to the south of Sevenoaks in Kent delivered a leave vote of 51.6% (again, without any postal votes).

Switching areas

The data obtained points to 269 areas of various sizes (wards, clusters of wards or constituencies) which had a different Leave/Remain outcome compared to the official counting area of which they were part.

This consists of 150 areas which backed Remain but were part of Leave-voting counting areas; and 119 in the other direction.

The detailed information therefore gives us an understanding of how the electorate voted which is more variegated than the officially published results.

Scotland

Scotland voted to Remain - but some wards backed Leave, analysis shows

Every one of Scotland's 32 counting areas came down on the Remain side. Yet, despite the fact that most Scottish councils did not give us much detailed information, we can nevertheless identify a few smaller parts of the country which actually backed Leave.

A cluster of six wards in the Banff and Buchan area in north Aberdeenshire had a strong Leave majority of 61%. There is much local discontent within the fishing industry of this coastal district about the EU's common fisheries policy.

An Taobh Siar agus Nis, a ward at the northern end of the Isle of Lewis in Na h-Eileanan an Iar (Western Isles), also voted Leave, if very narrowly.

And at a smaller geographical level, in Shetland the 567 voters in the combined polling districts of Whalsay and South Unst had an extremely high Leave vote of 81%. The island of Whalsay is a fishing community, where EU rules have been controversial and in 2012 numerous skippers were heavily fined for major breaches of fishing quotas, external.

London

Ealing and Hounslow are neighbouring multi-ethnic boroughs in the west of London with large Asian populations, where - in contrast to the national picture - non-white ethnicity was associated with voting Leave, particularly in Ealing. Both boroughs shared a varied internal pattern of prosperous largely white areas voting strongly Remain, poorer largely white areas preferring Leave, and the Asian areas tending to be more evenly split.

Ealing voted 60% Remain, with Southfield ward hitting 76%, but in contrast the Southall wards which are over 90% ethnic minority were close to 50-50.

In Hounslow the richer wards in Chiswick in the east of the area voted heavily Remain (73%), but the poorer largely white wards at the opposite western end in Feltham and Bedfont voted Leave (64-66%). Osterley and Spring Grove was also 63% Leave, the highest Leave vote in any individual ward in the UK with a non-white majority for which we have data.

The south London borough of Bromley narrowly voted Remain. Those parts which did not do so by a significant margin were the Cray Valley wards, largely poor white working class areas; and Biggin Hill and Darwin wards, locations to the south which contain more open countryside and lie outside the built-up commuter belt.

In Croydon in south London, places which voted Leave by substantial amounts were New Addington and Fieldway, neighbouring wards with large council estates.

Other areas

Beyond the areas with the strongest backing for Leave and Remain, examining the detailed breakdown of votes in various places gives greater insight into the pattern of support for the two sides - as can be seen from the following examples.

In several places (for example, Birmingham, Bristol, Nottingham, Portsmouth) there was a strong contrast between the Leave-voting populations of large, rundown, predominantly white, housing estates in the urban periphery, versus Remain-voting populations in inner city areas with large numbers of ethnic minorities and sometimes students.

Birmingham had several wards with large Remain votes, although the city as a whole narrowly voted Leave. These pro-Remain wards tended to be the more highly educated, better off localities, or minority ethnic areas which strongly backed Remain despite low levels of educational qualifications. I have written about this before.

In Blackburn with Darwen, Bastwell ward had the highest Remain vote at 65%, compared to only 44% in the area as a whole. This ward has an ethnic minority proportion of over 90%. Other Blackburn wards which voted Remain were also ones with high minority populations.

Bradford voted to Leave (54%), but the area included some starkly contrasting places which went over 60% Remain: the prosperous, genteel, spa town of Ilkley, and strongly ethnic minority wards in the city, such as Manningham and Toller.

Bristol voted strongly Remain on the whole (62%), but there were some striking exceptions, particularly the large, deprived, mainly white estates to the south of the city. Hartcliffe and Withywood backed Leave at 67%. Similar neighbouring wards (Hengrove and Whitchurch Park, Filwood, Bishopsworth and Stockwood) also voted Leave, as did the more industrial area of Avonmouth and Lawrence Weston to the north west of the city.

As a county Cornwall voted to Leave. But one of its six parliamentary constituencies, Truro and Falmouth, voted 53% to Remain, possibly linked to a significant student population.

In Lincoln, which voted 57% to Leave, Carholme ward stands out as very different - it voted 63% to Remain. This ward includes Lincoln University, and 43% of the residents are students

Middlesbrough voted 65% to Leave. As already noted, it had several wards with extremely high leave votes of over 75%. But one ward, Linthorpe, voted very narrowly to Remain - a comparatively well-to-do inner suburb which includes an art college; and another ward, Central, which contains Teesside University, nearly did.

Mole Valley in Surrey exhibited a dramatic contrast between two neighbouring districts with very different demographics and housing. The highest Remain vote was in the very prosperous location of Dorking South, which voted 63% Remain, but the neighbouring ward of Holmwoods, dominated by large estates on the edge of the town of Dorking, voted 57% Leave, the area's highest Leave vote.

Nottingham voted narrowly to Leave, but the inner city ward of Radford and Park voted 68% Remain. This has both a comparatively high proportion of ethnic minorities and considerable numbers of students from two nearby universities. There was a lot of variation within the area. Bulwell - a market town to the north of the city with many social problems - voted 69% Leave

There was also a high Leave vote in the housing estate locations of the Clifton wards in the south of Nottingham.

Oldham voted to Leave at 61%, but Werneth, the city ward with the highest ethnic minority population, voted Remain (57%). Other wards with high minority populations also voted Remain.

The central wards in Oxford had high Remain votes

In Oxford the cluster of polling districts which included Blackbird Leys and other deprived estates on the southern edge of the city voted to Leave at 51%. In contrast the central areas containing colleges, university buildings and student accommodation voted to Remain at over 80%.

Plymouth voted 60% Leave, but Drake ward which includes the university had the city's highest Remain vote at 56%.

Portsmouth was another place with wide variation. Paulsgrove ward, with its large estate on the edge of the city, had the highest Leave vote at 70%, whereas at the other end of the spectrum Central Southsea, an inner city ward and student area, voted 57% Remain.

Rochdale voted 60% Leave. The place which bucked this trend by voting 59% Remain, Milkstone and Deeplish, was the most predominantly ethnic minority ward. Central Rochdale had the second highest Remain vote and is the other ward that is mainly not white.

Walsall voted strongly Leave (68%). The only ward which voted Remain, Paddock, is both a comparatively prosperous and multi-ethnic locality.

The most local data

A few councils released their data at remarkably localised levels, down even to individual polling districts (ie ballot boxes) in the case of Blackburn with Darwen and Bracknell Forest, or clusters of two/three/four districts, in the case of Amber Valley, Brentwood, Sevenoaks, Shetland, South Oxfordshire, and Tewkesbury.

This provides very local and specific data, in some cases just for neighbourhoods of hundreds of voters.

At its most detailed this reveals that the 110 people who cast their votes in the ballot box at St. Alban's Primary School in central Blackburn split 56-52 in favour of Remain, with two spoilt papers.

It also discloses stark contrasts in some neighbouring locations. The 953 people who voted at Little Harwood community centre in north Blackburn had a Leave vote of only 31%, while the 336 electors who voted in the neighbouring ballot box at Roe Lee Park primary school produced a Leave percentage over twice as high, at 64%.

Postal votes

The very detailed data we obtained also provides some rare evidence on the views of postal compared to non-postal voters. Campaign strategists have often deliberated on whether the two groups vote differently and should be given separate targeted messages.

Most places mixed boxes of postal and non-postal votes for counting, so generally it's not possible to draw comparative conclusions. However there were a few exceptions which recorded them separately, or included a very small number of non-postal votes with the postals.

These figures indicate that postal voters were narrowly less likely to back Leave than voters in polling stations. Data covering five counting areas with about 260,000 votes shows that in these places the roughly one in five electors who voted by post backed Leave at 55.4%, one percentage point lower than the local non-postal support for Leave of 56.4%.

The counting areas involved are Amber Valley, East Cambridgeshire, Gwynedd, Hyndburn and North Warwickshire.

The data

Since the referendum the BBC has been trying to get the most detailed, localised voting data we could from each of the counting areas. This was a major data collection exercise carried out by my colleague George Greenwood.

We managed to obtain voting figures broken down into smaller geographical units for 178 of the 399 referendum counting areas (380 councils in England, Wales and Scotland, with a separate tally in Gibraltar, external, while in Northern Ireland, external results were issued for the 18 constituencies).

This varied between data for individual local government wards, wards grouped into clusters, and constituency level data. In a few cases the results supplied were even more localised than ward level. Overall the extra data covers a wide range of different areas and kinds of councils across the UK.

Electoral returning officers are not covered by the Freedom of Information Act, so releasing the information was up to the discretion of councils. While some were very willing, in other cases it required a lot of persistence and persuasion.

Some councils could not supply any detailed data because they mixed all ballot boxes prior to counting; some did possess more local figures but simply refused to disclose them to us. Others did provide data, but the combinations in which ballot boxes were mixed before counting were too complex to fit ward boundaries neatly.

A few places such as Birmingham, external released their ward by ward data following the referendum on their own initiative, but in most cases the information had to be obtained by us requesting it directly, and sometimes repeatedly, from the authority.

You can follow Martin Rosenbaum on Twitter as @rosenbaum6, external