Does by-election pain await Labour in its heartlands?

- Published

Two parliamentary by-elections, two weeks away.

Is Labour a sitting duck in its own heartland territory?

A quick road-trip to the West Midlands and the Lake District was enough to conclude that Labour can look forward to a sweaty, and quite possibly a painful night on 23 February.

Both seats would normally be considered "safe" for Labour.

But "normal" now seems a long time ago. Stoke voted 70% to 30% to leave the EU. In Copeland the margin was 60% to 40%. That would be enough to give Remain-supporting Labour sleepless nights.

Copeland by-election candidates

Stoke-on-Trent Central by-election candidates

But add to that the fact that, in 2015, UKIP came second in Stoke - 5,000 odd votes behind Labour.

Throw in Labour's long term deficit in the polls, which suggests former Labour voters have turned away from Jeremy Corbyn.

Then, chat to people in Hanley town centre - in the Stoke-on-Trent Central constituency - before travelling north and doing the same in Whitehaven, the large coastal town in the sprawling, and beautiful, Copeland constituency in the Lake District.

If you don't hear enough cause for Labour to fear losing one or both of these seats, you're not listening.

Dismal rating

In Copeland, the biggest employer by far is the Sellafield nuclear power plant.

In Whitehaven, where Sellafield has a large office block, Jeremy Corbyn's past opposition to nuclear power - which has since softened - comes up in almost every conversation.

The local grocer - whose family have run Kinsella's since the turn of the last century - told me customer after customer was switching allegiance away from Labour for that reason.

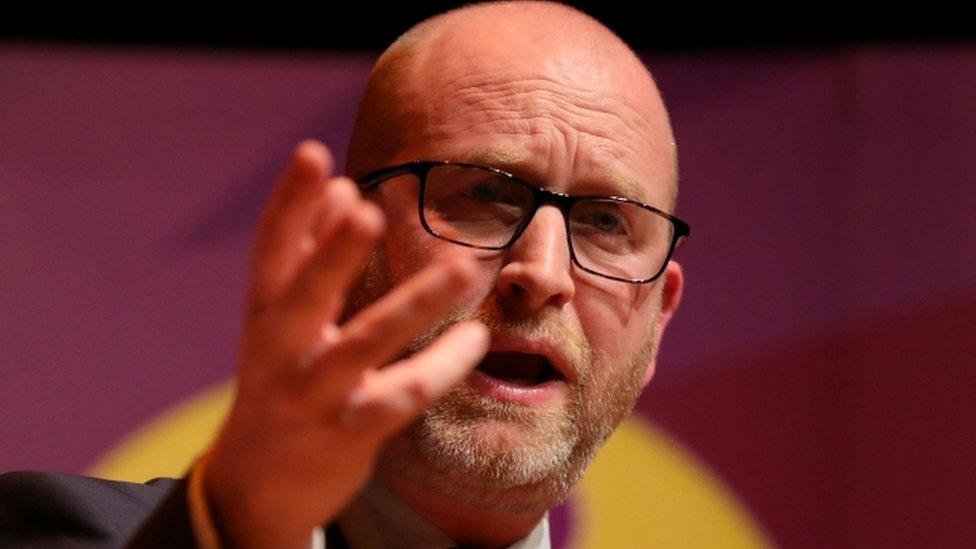

Could UKIP leader Paul Nuttall win the party's second seat?

That, and the doubts about Mr Corbyn's fitness to lead which have handed him a quite dismal personal rating of minus 40.

That's 46 points behind Theresa May who was the only national leader with a positive rating in the survey conducted by Yougov last week.

Strong identity

In Stoke, the UK Independence Party's new leader, Paul Nuttall, is standing as a candidate. UKIP has a great deal invested in this fight.

It's not clear whether the perception of an outsider parachuting into the seat - a charismatic Scouser seizing his chance in an area with a strong identity of its own - will count against Mr Nuttall and his party.

If UKIP fails it will hurt, and suggests the party lost its way when it lost Nigel Farage as leader.

So Labour will throw everything into both campaigns. Jeremy Corbyn's visited both, and will visit again.

Victory in both seats will buy time and space to try to regain ground, to try to recover from the visible splits which opened up so glaringly during debate and voting on the bill to begin Brexit.

But if Labour loses in either or both seats - each of which has been held by the party since 1935 - it means talk of existential crisis for the party.