Why has the UK become a nation of political swingers?

- Published

A few days ago, British politics saw a stunning by-election result in the Cumbrian seat of Copeland.

After electing Labour MPs for 80 years, voters changed their minds and elected a Conservative.

What makes voters do this, and why is swing voting on the rise?

Back in the 1960s, about 13% of voters would change which party they voted for, says Dr Jonathan Mellon from Nuffield College, Oxford.

In 2015, that was closer to 40%.

"A really large proportion of voters are swingers - and this has been steadily increasing in each subsequent election," says Dr Mellon.

There have always been some voters who changed their minds.

The classic swing voter has no particular allegiance to any one party, and may choose a different party from one election to the next.

Their decision can decide the outcome of an election, but this usually happens indirectly.

"Either you'll get swings from the major parties to minor parties - such as traditionally the Liberal Democrats but now also UKIP, the Greens, the SNP - or you'll see voters swing back to one of the major parties," Dr Mellon says.

Joe Twyman, head of political and social research at the polling company YouGov, analysed swing voting at the most recent general election.

"One way of shifting that surprised a lot of people was the move from the Liberal Democrats to UKIP, and when people saw the data on that they would say, 'Well hang on, that doesn't make any sense, the ideology and the policies of Liberal Democrats are very different from those of UKIP. Why should people do that?'

"But it's about protest."

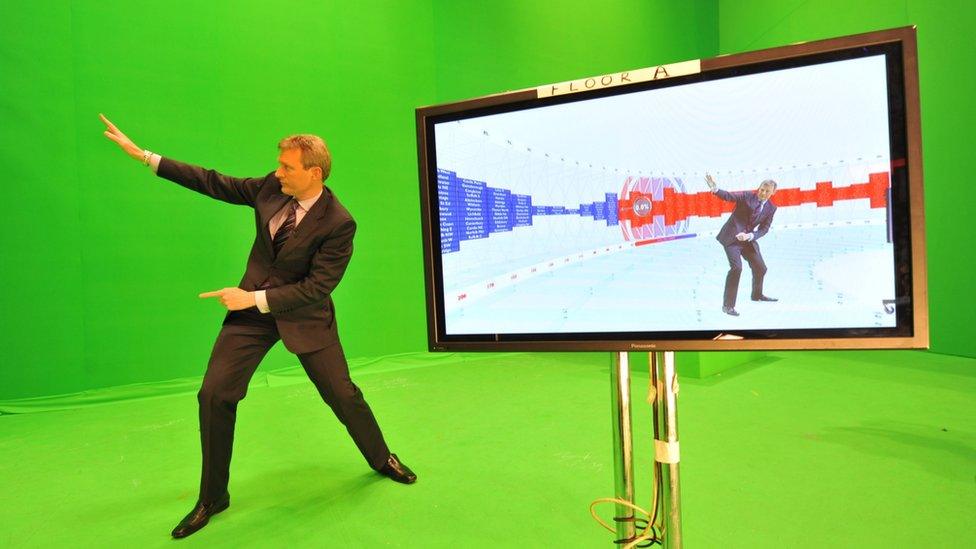

The 2015 general election is thought to have raised the profile of smaller parties

In the past few years, all the major parties have provided reasons for voters to turn against them.

The Conservatives damaged their reputation with Black Wednesday, a day-long economic crisis in 1992.

The Labour Party lost a million votes after the Iraq War, with many loyal members defecting to the Liberal Democrats or the Green Party.

Liberal Democrat activist Tom Southern witnessed voters turn against his party, angry with it for joining a Conservative-led coalition government and raising university tuition fees.

"It was clear immediately that around half the support had been wiped out within months if not weeks," he says.

And yet the coalition government was also beneficial to the smaller parties, including the Liberal Democrats.

The public saw that a minor party had teamed up with a major party and was now in government.

And this impression was reinforced during the 2015 general election campaign, when the leaders of seven different parties appeared on TV debates.

The media proclaimed that any one of the smaller parties might hold the balance of power.

This campaign proved to be a catalyst for voters.

One in every 12 people in the UK voted for UKIP.

One in two people in Scotland voted for the SNP.

It is much rarer for voters to switch between Labour and the Conservatives.

But the Copeland by-election is a reminder that this does happen.

James Tilley, professor of politics at the University of Oxford, has studied one reason why voters might make this move.

"In Britain it is definitely the case that older people are much more likely to vote for the Conservatives than younger people," he says.

Copeland aside, it is rarer for voters to swing between Labour and the Conservatives

As voters get older, they are about 20% more likely to vote for the Conservative Party.

But the reason for this is hard to identify.

"It could be that people born a long time ago are more likely to vote for the Conservatives," says Prof Tilley, "or it could be that as we get older we become more likely to vote for the Conservatives."

He leans towards the second explanation.

"People generally become a bit more resistant to change as they get older, and I think also that they tend to become less idealistic," says Prof Tilley.

"So if parties on the right represent a platform which is more favourable to the status quo, and more about pragmatism than it is about idealism, that might be more attractive to older people than younger people."

Swing voting is a nightmare for the parties.

In the past, MPs relied on their core vote to back them no matter what.

Now, they have to spend far more of their time campaigning to keep their seats and far less time legislating.

Politicians argue that democracy is less efficient when voters keep changing their minds.

But Rosie Campbell, professor of Politics at Birkbeck, University of London, thinks that politics works best when voters are willing to change their minds.

"In the past, voters stuck with parties that had let them down, or had morphed into something they didn't like," she says.

"Even if the future is more chaotic, the rise of the swinging mindset might just be the change our political system so desperately needs."

Analysis: How Voters Decide, presented by Prof Rosie Campbell, is on BBC Radio 4 at 20:30 on Monday 27 February and available later via BBC iPlayer.

- Published24 February 2017