The May hegemony: How long can it last?

- Published

Mrs May did not sprawl on the Royal throne to glare at their lordships. She merely glowered from its steps. The heralds might call it "the perch presumptive". But she might as well have done so: she is queen of all she surveys. The Copeland by-election has established the May hegemony. How long it lasts is another matter.

Her power is unchallenged. There is little serious opposition within her once fractious party and little outside it at the moment, at least not in England.

The Stoke result is far from good for Labour, external: it won only because the Conservative vote held up, and UKIP failed to increase its share significantly.

Copeland though, was the killer. When by-elections go wrong for governments the journalistic cliche is that it's "the final nail in their coffin". This time the nail is in the other foot.

Mrs May delights in facing what some critics have described as a "zombie" opposition. Jeremy Corbyn's many internal opponents believe they are lurching towards an apocalypse in 2020, their leader undead and unkillable. They may be wrong about the chance of renaissance but their doubts make it even less likely.

Meanwhile, like some doomsday machine which has completed its mission, UKIP seems to be counting down to its own destruction - it may not actually blow up but Paul Nuttall's by-election failure is now being eclipsed by new stories of internal squabbles, external.

The Conservatives won in Copeland for the first time in more than 80 years

While they were busy trying to pinch Labour's voters, they didn't notice Mrs May had nicked their clothes.

The Liberal Democrats are the natural repository for the unreconciled Remain voters. But they are not exactly radiating raw heat.

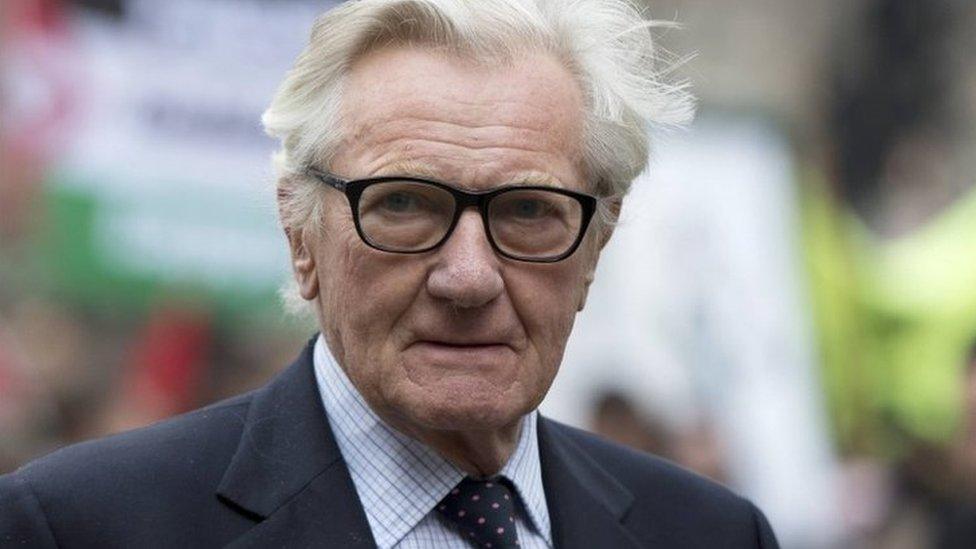

Tony Blair's big speech, external turned out to be less of a clarion call and more a virtuoso jazz solo, brilliant but gaining no new fans. The same could be said for John Major's big gig.

For now the May hegemony looks unassailable.

And remember, she's didn't get here by accident. It just looks that way. Mrs May positioned herself perfectly to be the heir apparent in the case of either Brexit result. Cameron's unexpectedly abrupt departure had huge, unexpected consequences.

We in the UK often overstate our own importance. But our prime minister is unique in the world at the moment. She did not summon or support the wave of populism which propelled her to power. But she has ridden it with skill.

Jeremy Corbyn has urged Labour to "remain united", and not to "give up"

She has firmly and loudly proclaimed three big things, so obvious now, that it seems like any Conservative prime minister would have said them after a Brexit vote. They wouldn't have, though.

Whatever their policy, PM Johnson or Gove would have wanted to sound conciliatory in victory towards their defeated opponents, inside and outside the party. There could have been mollification on migration while the hand of friendship would have been thrust towards Remainers. That in itself would have opened up a space for debate, which Mrs May has closed down.

She, indeed, exhibits such a convert's zeal for the verdict of the people that neither those who are delighted nor those who are nauseated, peer beyond her enthusiasm to perceive the tactics.

Those three big things?

First that Brexit will happen: no ifs, no buts. Second, that it was largely about immigration. Thirdly, critically, that it was also about something else.

She proclaims it was a howl of pain from those who are economically adrift in a society where there is growing inequality.

In the Spectator, James Forsyth notes correctly that she is attempting to plot a middle course, external, a third way, between the two clashing ideologies which have, in part, replaced left and right as the burning divisions of our time: nationalism and globalisation.

The UK government's Brexit White Paper has opened a wide debate on its negotiating aims

To square this circle will need her to display even more ingenuity than is so far on display. Indeed, if she can't reconcile contradictory facts she will have to make choices which will disappoint someone or other. That could break the hegemony.

Take Brexit itself.

The government White Paper on leaving the EU, external has been mocked for its vacuity. In fact, it is very revealing. It strikes a pose of very hard Brexit while hinting at the desirability of the opposite.

It declares controlling EU immigration is "complex", adding there may be "a phased process of implementation" after businesses have said what they want. I await the reply of farmers, caterers and minicab firms with interest.

Indeed David Davis, external and Amber Rudd, external agree migration will continue for a good while yet. That could be a focus for new opposition.

Then there are tariffs. Portions of the White Paper could have been ripped from Remain propaganda.

They give the example of Airbus, where the wings are built in Wales with parts crossing back and forth promiscuously between borders.

The government argues it needs "tariff-free trade in goods that is as frictionless as possible between the UK and the EU".

The British Chambers of Commerce says that if the UK can't get such a deal, Brexit should be put on hold, external. Others will argue for World Trade Organization rules or retaliatory trade barriers of hard Brexit.

Businesses will closely monitor the government's Brexit strategy on immigration

If the sharp edges of this square can't be smoothed into soothing curves, then the hegemony could crack.

Then there's Mrs May's promise of a government which "works for everyone, not just the privileged few". Does she just mean a growing economy or is she really talking about a radical redistribution of wealth and power?

And if those despairing coastal towns, and abandoned swathes of our post-industrial kingdom still feel left behind in 2020, what then will they think of the establishment in power?

Hegemony never lasts. But it can last long enough.

While I love the old saying, "fine words butter no parsnips", plenty of political parsnips are positively slippery with rhetorical promises which render reality more palatable.

As Abraham Lincoln didn't say, external: "You may not be able to butter all of the parsnips all of the time, but you can probably make enough of them glisten appetisingly long enough to be swallowed at the next election."

- Published24 February 2017

- Published26 February 2017

- Published24 February 2017

- Published26 February 2017