Brexit: Article 50 has been triggered - what now?

- Published

The letter triggering Article 50 has been handed over to the European Council

Britain is officially on its way out of the European Union after 44 years as a member after invoking a part of European law known as Article 50 on Wednesday.

What exactly happened?

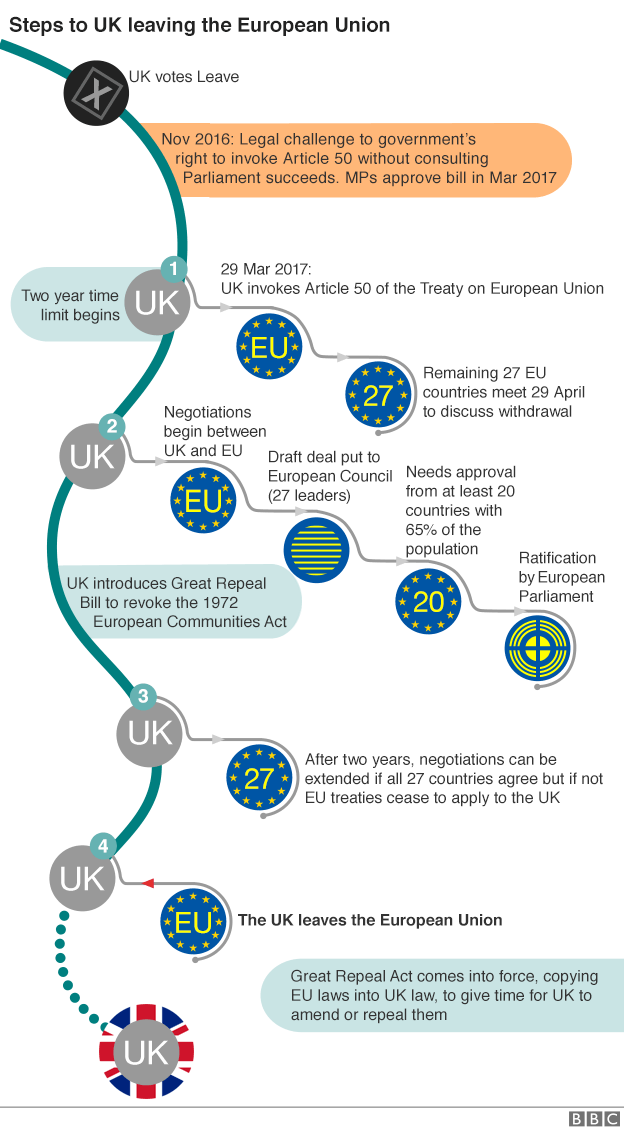

Nine months after the UK voted to get out of the European Union in a referendum, Prime Minister Theresa May activated the official mechanism that will make it a reality - Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty.

On Tuesday night, she signed a letter triggering the process, which was handed over to the European Council's president Donald Tusk at around 12:20 BST.

This was followed by a statement from Mrs May to the House of Commons, where she said now was "the moment for the country to come together".

What happens next?

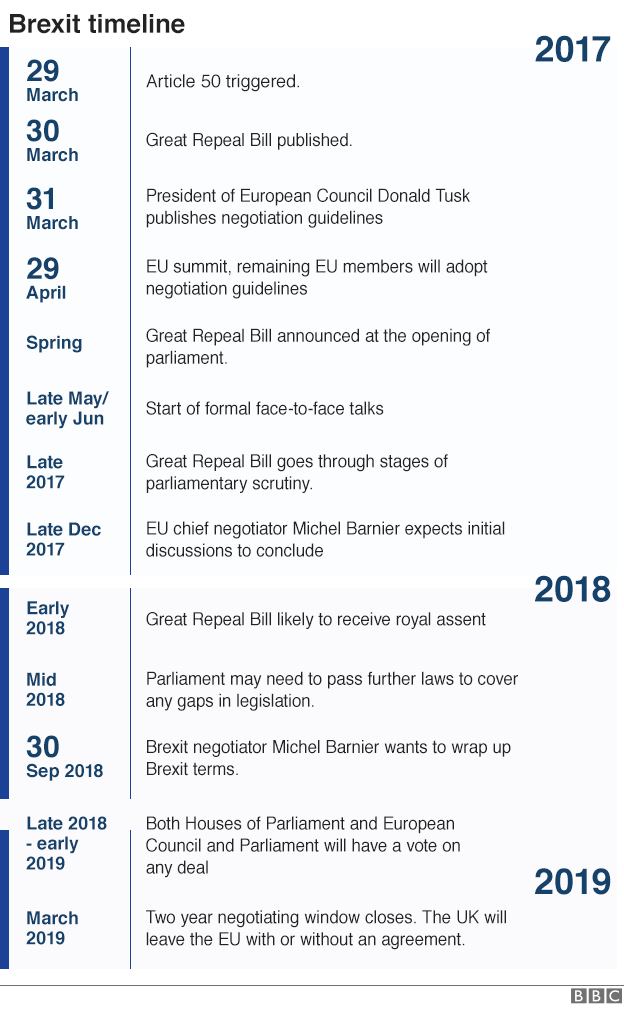

Talks will get under way with EU officials. But the real hard work will not start until May or June when negotiations with other EU countries are expected to start. These talks are expected to end in autumn next year - and then MPs at Westminster, the European Council in Brussels, and the European Parliament will each get a vote on any deal that has been agreed.

So when does the UK actually leave?

The time-frame allowed in Article 50 is two years - and this can only be extended by unanimous agreement from all EU countries.

If no agreement is reached in two years, and no extension is agreed, the UK automatically leaves the EU and all existing agreements - including access to the single market - would cease to apply to the UK. If that happens, Brexit Day would be Friday, 29 March 2019.

What is Article 50?

Article 50 is the plan for any country that wishes to exit the EU. It was created as part of the Treaty of Lisbon - an agreement signed up to by all EU states which became law in 2009. Before that treaty, there was no formal mechanism for a country to leave the EU.

It's pretty short - just five paragraphs - which spell out that any EU member state may decide to quit the EU, that it must notify the European Council and negotiate its withdrawal with the EU, that there are two years to reach an agreement - unless everyone agrees to extend it - and that the exiting state cannot take part in EU internal discussions about its departure.

Any exit deal must be approved by a "qualified majority" (72% of the remaining 27 EU states, representing 65% of the population) but must also get the backing of MEPs. The fifth paragraph raises the possibility of a state wanting to rejoin the EU having left it - that will be considered under Article 49.

The full text can be found here, external.

Can it be reversed?

No country has ever left the EU and Article 50 does not explicitly say whether the process can be halted. The UK government has been unable to make any definitive legal statements on the issue.

However, in her speech to the House of Commons on Wednesday, Theresa May said "there can be no turning back" and in the recent UK Supreme Court case on Article 50, both sides assumed it was irrevocable.

But the European Council President Donald Tusk as said he believes Article 50 can be reversed.

On his side is veteran British diplomat Lord Kerr, who wrote Article 50. He told the BBC in November 2016 "you can change your mind while the process is going on". But he added he did not think any politician in Britain would allow such a U-turn.

Why was there such a long wait to trigger it?

May announced in October last year that she would formally notify the European Council by the end of March, arguing that she did not want to rush into the withdrawal process before UK objectives had been agreed.

What will negotiations cover?

EU migrants have protested outside Parliament

The letter to Mr Tusk outlines the UK's seven negotiating principles. It reads:

We should engage with one another constructively and respectfully, in a spirit of sincere cooperation

We should always put our citizens first

We should work towards securing a comprehensive agreement

We should work together to minimise disruption and give as much certainty as possible.

We must pay attention to the UK's unique relationship with the Republic of Ireland and the importance of the peace process in Northern Ireland

We should begin technical talks on detailed policy areas as soon as possible, but we should prioritise the biggest challenges

We should continue to work together to advance and protect our shared European values

The UK has said a trade deal should be part of negotiations - EU representatives have suggested the withdrawal agreement and a trade deal should be handled separately.

Other issues which are likely to be discussed are things like cross-border security arrangements, the European Arrest Warrant, moving EU agencies which have their headquarters in the UK and the UK's contribution to pensions of EU civil servants - part of a wider "divorce bill" which some reports have suggested could run to £50bn.

The government published a report before the UK's 2016 referendum on the process for withdrawing from the European Union, suggesting other areas which could be debated. Read them here.

Who is doing the negotiating?

The European Commission - the EU's civil service - has created a task force headed by Michel Barnier, who will be in charge of conducting the negotiations with the UK.

On the UK side, the overall responsibility for Brexit negotiations resides with the prime minister, who is supported by the Department for Exiting the European Union led by David Davis. Here is a pen portrait of the key players.

What if no deal is reached after two years?

In this case, it is assumed UK trade relations with the EU would be governed by World Trade Organisation rules.

Some ministers have suggested there could be a transitional period once the UK leaves the EU, to avoid a "cliff edge" and phase-in new arrangements.

Will Parliament have a say?

Article 50 does not give any details on the role of the withdrawing member state's parliament

While Article 50 says any deal will need the "consent of the European Parliament", it doesn't say anything about the parliament of the departing state.

However, after appearing to resist calls at first, the prime minister said in January both the Commons and Lords would get a vote on the final deal. The UK Parliament will also scrutinise the government's work on Brexit through parliamentary debates, select committee work, and votes on proposed legislation.

Will the UK still play a full part in the EU during Brexit negotiations?

The UK will remain a member of the EU during negotiations, but it has given up its rotating presidency of the European Council - which was scheduled for the second half of 2017 - to concentrate on Brexit.

Can the UK negotiate trade deals with other countries now?

International Trade Secretary Liam Fox confirmed the UK was not able to negotiate any new trade agreements while it was in the EU

No. While the UK is still part of the European Union, it cannot independently negotiate any international trade agreements with non-EU countries, without violating EU treaties.

But there could still be some general discussions about trade and possible partners are sure to take interest in the negotiations.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published8 March 2017

- Published13 February 2017