Is Philip Hammond's tax U-turn the quickest ever?

- Published

Chancellor Philip Hammond may have set a record by scrapping a planned rise in National Insurance for the self-employed less than a week after announcing it - here are some other contenders for quickest political U-turn of recent times.

Pasty tax (announced March 2012 - abandoned May 2012)

The pasty tax row briefly gripped Westminster in 2012

The pasty tax became synonymous with George Osborne's so-called Omnishambles Budget of 2012. The chancellor was forced to backtrack on several proposed tax rises - including charging 20% VAT on alterations to historic buildings and static caravans - in the weeks after his statement.

But it was the plan to charge 20% VAT on hot savoury food which caused Mr Osborne the most indigestion.

He had proposed that all food sold "above ambient temperature" - including pasties, pies and sausage rolls - should include VAT to close a tax loophole.

It might have looked innocuous on paper but the idea caused an outcry among businesses up and down the country, who argued it would hit trade and jobs.

The chancellor and Prime Minister David Cameron also faced claims they were out of touch with the pasty-munching masses.

The measure was finally dropped in late May, about two months after it was first announced.

Tax credit cuts (announced June 2015 - scrapped November 2015)

The government attempted to tackle the tax credit bill but had to back down

Towards the end of his time as chancellor, George Osborne performed another screeching U-turn, this time over cuts to tax credits for low-income families in work.

It was part of a £12bn cut to the welfare bill which the Conservatives had promised before the 2015 election but had given very little detail of before the poll.

In an "emergency" June Budget after David Cameron's election victory, the chancellor announced that spending on tax credits had ballooned since 1997 and he planned to reduce the income threshold from £6,420 to £3,850 and restrict tax credits and Universal Credit to the first two children.

Labour, who were in the throes of a leadership contest at the time, were somewhat slow to respond but soon the opposition galvanised themselves against the proposal, which was also criticised by Tory backbenchers and charities, who said it would cost many families £1,000 a week.

The government suffered a damaging defeat in the House of the Lords, where peers backed Labour calls to delay the plans. Mr Osborne finally conceded defeat in November's Autumn Statement when he said the plans would simply not be implemented.

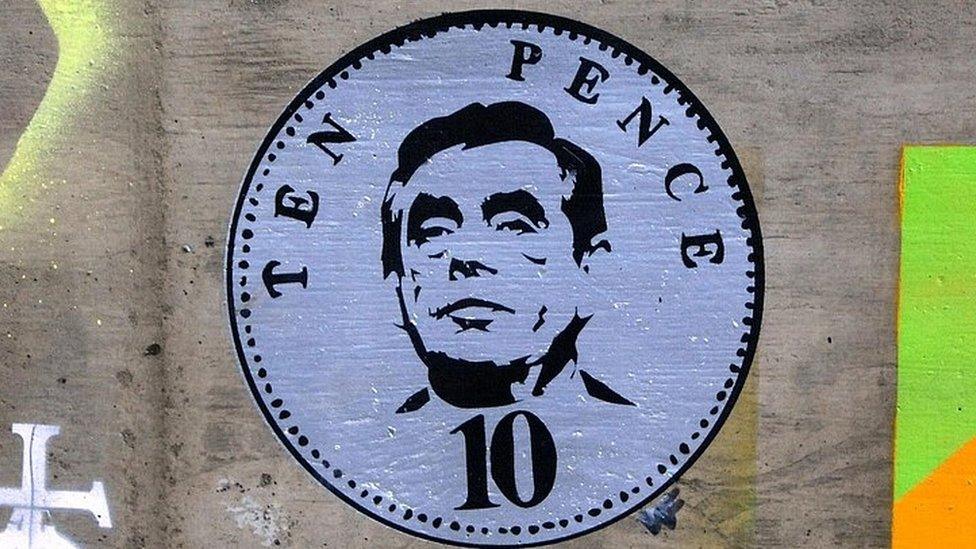

10p tax rate (announced March 2007 - revised May 2008)

The 10p tax rate row was an albatross around Gordon Brown's neck

Gordon Brown loved to wrongfoot the opposition by springing a surprise at the end of his Budget speeches - but it was his own side that was in uproar when he cut 2p from the basic rate of income tax in his 10th and final Budget in March 2007.

He announced that the 10p starter rate would be scrapped at the same time - and initially refused to accept that there would be any losers from this measure.

The then chancellor argued those earning less than £17,000 would not be disadvantaged because of a commensurate increase in working tax credits but Labour MPs were not impressed, accusing the chancellor of clobbering the poor to fund a middle-income tax cut.

The change was not due to come into force until May 2008 and Mr Brown had plenty of time to find a way out. He was eventually forced to agree a £2.7bn compensation package for those set to lose out, by raising income tax allowances.

By that point, of course, Mr Brown had succeeded Tony Blair as prime minister and the simmering row was not helped by those Labour MPs already unhappy with his leadership.

Although this was strictly a partial U-turn - the 10p rate was never restored - the episode dragged on for much of his premiership. Chancellor Alistair Darling was forced to make further concessions in 2009 when Labour MP Frank Field led a revolt against the fairness of the remedial measures.

The poll tax (introduced in 1989 - axed in 1992)

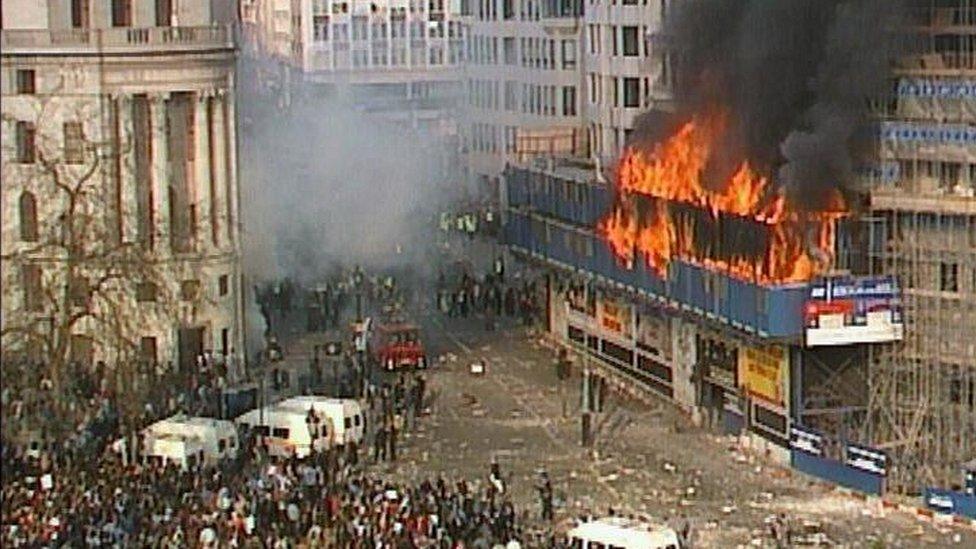

Protests around the country, including one in central London, turned violent

This might well be the mother of all tax U-turns, as it led to the downfall of a prime minister.

Conservatives had long seen domestic rates, based on the rental value of properties, as unfair and out of date.

The system Margaret Thatcher devised after the 1987 election to replace them - a single flat-rate per-capita tax on every adult, set by local authorities - was dubbed the Community Charge by her government. But everybody else called it the Poll Tax.

It was first introduced in Scotland at the end of 1989 and rolled out in England and Wales in early 1990. It proved hugely unpopular and sparked large protests, culminating in riots in London and other cities in the Spring of 1990.

The social unrest, although condemned by politicians at the time, fuelled the impression of a government that was deeply out of touch after 11 years and before the year was out Mrs Thatcher had been ousted.

After taking over as Tory leader and prime minister, John Major ditched the poll tax and reverted to a system based on property values in the form of the council tax in 1992. Unlike its predecessor, the council tax took ability to pay into account.

- Published15 March 2017