Decoding Russia's response to Johnson's cancelled trip

- Published

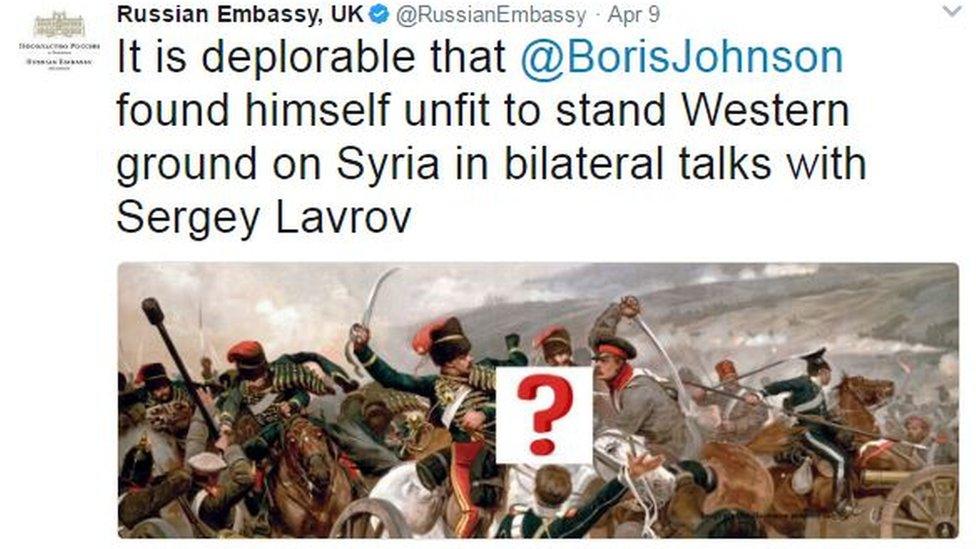

The Russian embassy in London called Mr Johnson's cancellation deplorable and absurd

The Russians have reacted with a mixture of contempt and fury to the cancellation of the foreign secretary's trip to Moscow.

It suggests they do, perhaps surprisingly, care quite a lot about it.

In a series of tweets, the Russian embassy in London mocked the foreign secretary, calling his decision "deplorable" and "absurd" and linking to an image of the Charge of the Light Brigade and Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture.

That was the year that a minor war between Britain and Russia, provoked by a Russian alliance with France, came to an end, when Napoleon invaded Russia. The US was on the French side. The message is a little hard to decode, beyond poking fun at Boris.

The Kremlin is less mischievous, and more straightforward.

It "doubts in the presence of added value in speaking to the UK, which does not have its own position on the majority of present-day issues, nor does it have real influence on the course of international affairs, as it remains 'in the shadow' of its strategic partners. We do not feel that we need dialogue with London any more than it does."

One of the Russian embassy's tweets referred to the Charge of the Light Brigade

This has both the whiff of wounded pride and the smell of an unpalatable truth. Both interpretations have something in them, but disguise a more profound method in their mockery.

Russia's intervention in Syria had many fathers, but no doubt part of President Putin's purpose was to establish that modern Russia, just as much as the old Soviet Union, matters on the world stage - a force to be reckoned with, on a par with China and the US.

So a snub from Britain, definitely lower down the league table of powerful nations, stings a little bit. It is also easy to take a tilt at the UK and Boris Johnson.

We do, in military, intelligence and diplomatic terms, in that old cliche, punch above our weight. We matter more, in those terms, than Sweden or Brazil, Spain or Italy. But the weight of our history makes many of us think we matter more than we do.

We have lost an empire and don't particularly like finding ourselves in a subordinate role, perhaps not always as important as France and Germany. Absurdly, our media and politicians sometimes like to pretend we are almost on a par with the United States, nearly equal partners rather than occasionally useful allies.

The Russians are deeply aware of how much power they have lost. We in Britain simply pretend it's not the case. So the Kremlin prodding a finger in this wound makes us shiver a little bit.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is due to visit Moscow on 12 April

I have no idea whether US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson asked tentatively and politely that Boris should call off his visit, virtually ordered it, or whether the proposal came from the Foreign Office. But there's no doubt we are doing what the Americans want, and waiting for them to explain what they want to happen next.

This is what the Russians really hate. Like the Chinese, they would rather have one-on-one, bilateral relations, with other smaller nations. It is why they would love to see the European Union collapse, and support parties which wish to see that too. They don't like other countries acting against them in concord, matching their mass.

If they don't like the EU, they feel even more strongly about European nations acting together with the US. Bundle in the G7 nations of Japan and Canada, and you have something that amounts to '"the West" - the Soviet Union's old adversary.

Though the faces may change, the G7 group remains, to some, the face of "the West"

If they had hoped the US would turn inward, not even leading from behind, but wandering off in a disinterested daze, then recent developments seem to suggest they won't get their wish.

So Boris Johnson's cancelled trip to Moscow makes diplomatic sense and shows a due sense of proportion about our nation's power. But it is still not great for the man himself. Hanging over all this is the feeling that he's not to be trusted, that he'd somehow make a mess of it all.

The Russians keep using the term "clown" and hinting that he is out of his depth. Some in the Foreign Office seem to agree. So do opposition politicians.

It may be desperately unfair, based on the fact he makes a few broad jokes in a world where many others have carefully crafted pokers inserted somewhere about their person.

But Boris has become a politician it is easy not to take seriously, a doddle to ridicule. President Trump's example suggests that's not entirely a bad place to be, but at the moment it has made it easier for people at home and abroad to deride an entirely standard diplomatic response.

- Published2 May 2023

- Published6 April 2017