Theresa May says no to general election TV debates

- Published

- comments

A look back at the main arguments during the leaders' debate

Theresa May will not take part in TV debates ahead of the planned general election, she has told the BBC.

The prime minister told BBC Radio 4's Today she preferred "to get out and about and meet voters".

ITV has become the first broadcaster to confirm a debate ahead of the poll on 8 June, announced by Mrs May on Tuesday.

Labour's Jeremy Corbyn accused the PM of "dodging" a head-to-head showdown and the Lib Dems urged broadcasters to "empty chair" her.

Mrs May has promised a "strong and stable leadership" if she wins. MPs are expected to back the early election in a vote on Wednesday.

A Number 10 source has told the BBC's political editor Laura Kuenssberg that the prime minister will not be changing her position, despite ITV's announcement.

Mr Corbyn said the PM's stance was "rather strange", adding: "I say to Theresa May, who said this election was about leadership, Come on and show some.'

"Let's have the debates. It's what democracy needs and what the British people deserve."

Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron added: "The prime minister's attempt to dodge scrutiny shows how she holds the public in contempt.

"The British people deserve to see their potential leaders talking about the future of our country."

So are any debates scheduled to go ahead?

ITV is the first broadcaster to confirm a debate. No details have been released about the format or the date, but Julie Etchingham is expected to be the host, as she did in 2015.

A BBC spokesman said it was too early to say whether the broadcaster would put in a bid to stage a debate but its head of newsgathering, Jonathan Munro, told the Daily Telegraph that he did "not want to get in a position where any party leader stops us doing a programme that we think is in the public interest".

David Dimbleby, who hosted the BBC leaders' debates in both 2010 and 2015, said a refusal to take part in TV showdowns with her rivals could be "rather perilous" for Mrs May.

"I don't think other parties will refuse to take part in debates, and I wonder whether Number 10 will stick with that, because it may look a bit odd if other parties are facing audiences and making their case," he said.

Why are TV debates important?

They are a chance to hear, in a prime-time TV slot, what party leaders offer and how robustly they can defend their ideas.

Political leaders' TV debates featured in the last two general elections, in 2010 and 2015.

And they took different forms at each - in terms of the line-up, questioning, topics and how they debated. A set of rules were thrashed out, external between party and broadcaster beforehand.

"I agree with Nick", external was the almost gameshow-like, standout legacy of the first 2010 encounter.

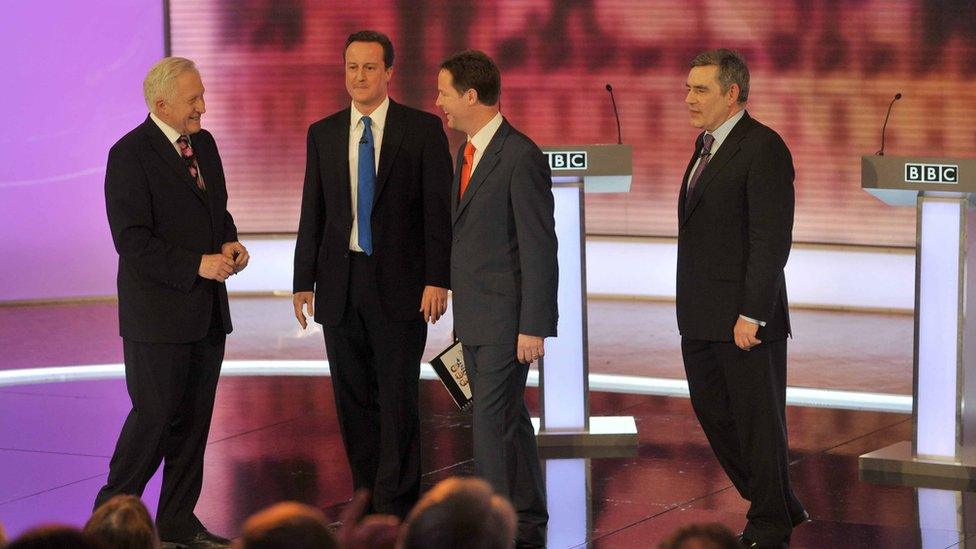

It saw then Prime Minister Gordon Brown and Tory leader David Cameron find common ground with Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg - who went on to be deputy PM in the coalition government.

It was the first of three 90-minute debates on ITV, Sky and the BBC. Separate leaders' debates were held in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Do they make a difference?

Viewer ratings in 2010 varied - from a peak of 10.3m watching the first debate to 4m for the second.

The format changed in 2015 to provide a more open mix - seven leaders taking part in one debate; a second programme of just opposition chiefs; Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish debates.

There were also specials with Mr Cameron, then Labour leader Ed Miliband, another with the addition of Mr Clegg. But they did not debate 'head-to-head'.

Did all those permutations change anything? Again millions watched and research shortly after the 2015 election found 38% of voters were "influenced" - more than general TV news coverage or party political broadcasts.

Later on, researchers found they played a "crucially important civic role" in reaching those often reluctant younger or first-time voters and piquing interest.

That may be positive for democracy, but it is clearly not perceived as decisive, given Theresa May's current no-debate stance.

Her refusal may be seen by some "a bit chicken", as the BBC's Media Editor Amol Rajan observes here, external.

But, he says, why would she risk it, and give her opponents a formal platform at the same time?