Tony Blair's legacy 20 years on

- Published

Watch: How the BBC covered this day 20 years ago

On Monday, it was 20 years to the day that Tony Blair won a landslide general election victory for Labour - how did he change the country and what is left of his legacy?

"A new dawn has broken, has it not?"

With these words, spoken to a cheering crowd of supporters as the sun rose over London's South Bank, Tony Blair ushered in the first Labour government in 18 years.

It was a typically snappy Blair phrase, yet also slightly hesitant, as if he could not quite believe what he had just done.

Blair was, by all accounts, a nervy companion on election night, refusing to believe he was on course to a stunning victory even as it was becoming obvious to all around him.

He did not share the euphoric mood of supporters. "I was scared," he later wrote in his memoirs.

It was a Labour landslide of historic proportions, handing Blair a Commons majority of 179, although the collapse in the Tory vote made it appear more dramatic. John Major's Conservatives had won more votes in 1992 - 14,093,007 - than Blair's 1997 total of 13,518,167.

But none of that mattered to the ecstatic crowd at the Royal Festival Hall, as Blair sketched out, in vague but confident terms, his vision of a modern, united country fit for a new millennium. A country for the "many not the few".

It is striking now to hear how much of his eight-minute speech was directed at the party's old guard.

"We have been elected as New Labour and we will govern as New Labour," he told his audience, as a warning shot across the bows of those who had opposed his "modernisation" of the party every step of the way.

The country

Blair came to power at a time of almost giddy optimism, in contrast with what was to come. The end of the Cold War and booming economies in the West, driven by advances in technology, created a brief window where peace, stability and rising living standards looked like they might become the norm.

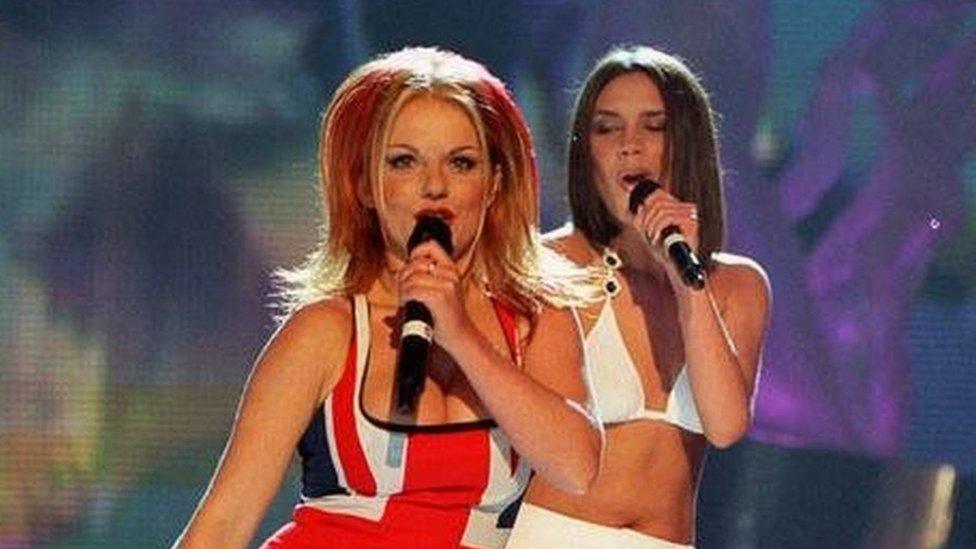

Britain was in the middle of a pop culture revival, built around swaggering self-confidence and semi-ironic celebrations of Britishness. The Union Jack was back - on Noel Gallagher's guitar and Geri Halliwell's mini dress at that year's Brit awards.

The Cross of St George had also been rehabilitated, as a new breed of middle class football fan cheered England to the semi-finals of the Euro 96 tournament.

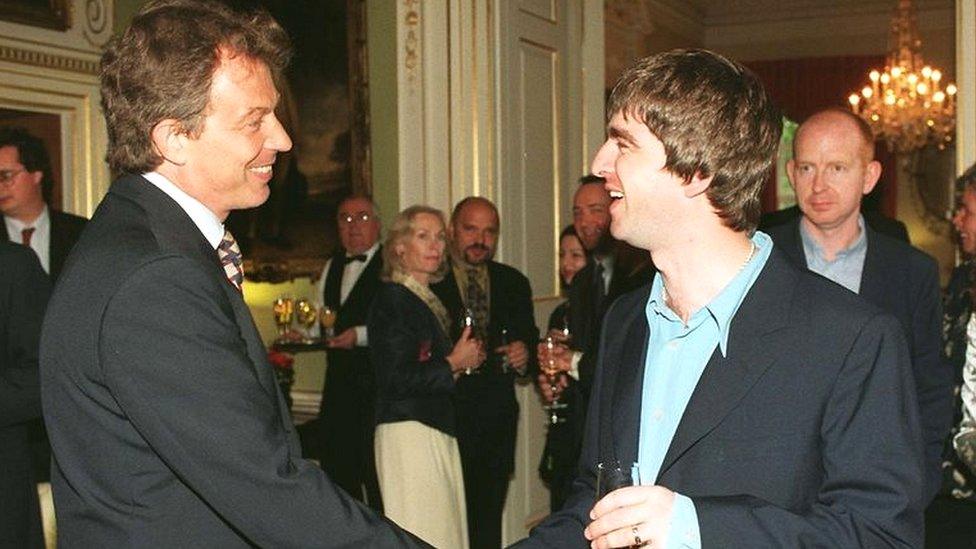

Blair rode the "Cool Britannia" wave for all it was worth. At 43, the former lead singer of Ugly Rumours - his student band - badly wanted to be seen as the first rock and roll prime minister.

And for the briefest of moments, it seemed to work, as he played host to the stars of Britain's "creative industries" at a Downing Street reception weeks after taking office.

The Cabinet

The voting public might have bought into New Labour's blend of Thatcherite free market economics and social justice, but it never had very deep roots in the Labour Party itself.

It was the product of a tight-knit group headed by Blair, Gordon Brown, Peter Mandelson and media chief Alastair Campbell.

Blair's first cabinet was a mix of old and new Labour figures (although the hard left was banished to the wilderness).

"Traditional values in a modern setting", as John Prescott, a man who straddled the new/old divide with more agility than he was often given credit for, would say with a knowing smirk.

They were a diverse bunch - with more women than had ever sat in a British cabinet before and the first openly gay cabinet minister, Chris Smith.

There were some big hitters, such as Robin Cook at the Foreign Office and Jack Straw at the Home Office, even though very few - including Blair himself - had ever sat behind a ministerial desk before.

And it quickly became clear that only Blair and Chancellor Gordon Brown really mattered when it came to the big decisions. But rather like Oasis's Gallagher brothers, their successes were quickly followed by growing stories about their rivalry.

But despite their increasingly fractious relationship - the TBGBs as they became known - there was no official split as they dominated Britain's political landscape for the next decade.

Ministers seemed to come and go with dizzying speed, as the cabinet reshuffle became Blair's signature move, but the Blair/Brown axis somehow stayed in place.

Twenty years on and only three MPs - Harriet Harman, Margaret Beckett and Nick Brown - from that first Cabinet line-up are still in the Commons.

Mo Mowlam, Donald Dewar and Robin Cook are no longer with us. Most of the rest, including the now Lord Prescott, Alistair Darling and David Blunkett, have taken up seats in the House of Lords.

Did they achieve what they set out to do?

The policies

The Blair government came to power on the back of relatively modest proposals on a pledge card brandished relentlessly through the 1997 election campaign. They were cutting class sizes, "fast track" punishment for young offenders, cutting NHS waiting lists, getting 250,000 under-25-year-olds "off benefit and into work" and "no rise in income tax rates".

But the new government did not lack ambition.

Labour's 1997 manifesto also included a minimum wage and plans for devolved government in Scotland and Wales.

And on the day after their election victory, Gordon Brown surprised everyone by handing control of interest rates to the Bank of England - a move that would have far-reaching consequences for the economy.

Blair was also determined, like many a prime minister before and since, to fix some of the country's longstanding social problems.

One of his top priorities was reform of the UK's social security system to make work pay. He appointed Labour MP Frank Field to "think the unthinkable" on welfare and promptly sacked him when he did just that (although it was Field's falling out with his boss Harriet Harman that probably sealed his fate).

Twenty years on and welfare reform remains a work in progress.

The gap between rich and poor remained more or less the same during the Blair years, according to analysis by the Resolution Foundation, external, although there was a big increase in pay at the top end of the income scale.

Education was Blair's other top priority. He oversaw a big expansion in higher and further education, and poured money into early years learning, as well as pioneering academy schools.

His first term was characterised by caution on tax and public spending, thanks to Labour's commitment to stick to tight Conservative spending limits for the first two years.

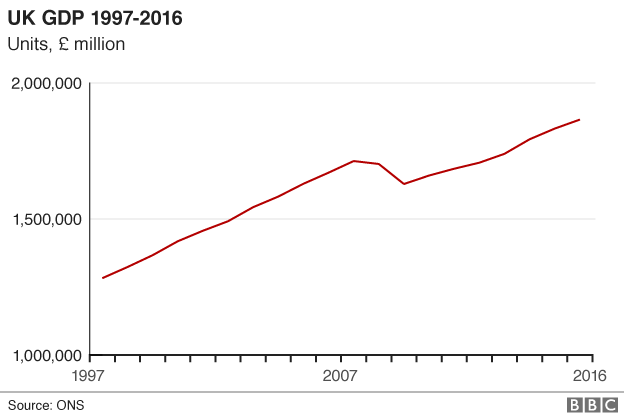

That changed after the party's second landslide election victory in 2001, when billions began to pour into the health service and education, on the back of a booming economy. Outcomes improved as a result.

Iraq and immigration

But perhaps the biggest change that happened to Britain during his time in power was never explicitly spelled out in a Labour manifesto.

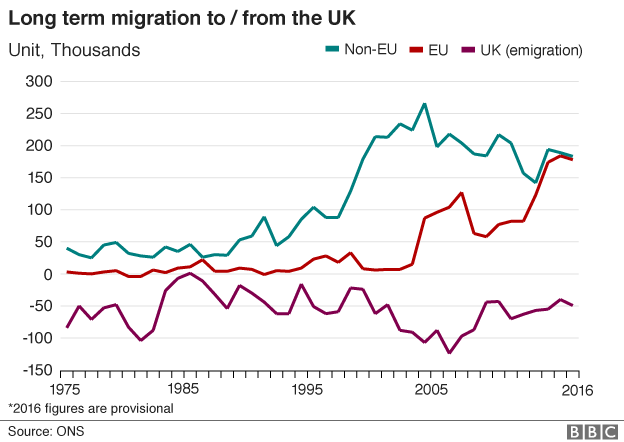

The UK, Sweden and the Republic of Ireland were the only EU nations not to temporarily restrict the rights of people from eight new member countries, including Poland and the Czech Republic, to live and work in their countries.

Blair's 2004 decision to open the door to East European migration was entirely in keeping with his values as an ardent pro-European, who had championed the eastward expansion of the EU and who believed globalisation and flexible labour markets were the answer to industrial decline.

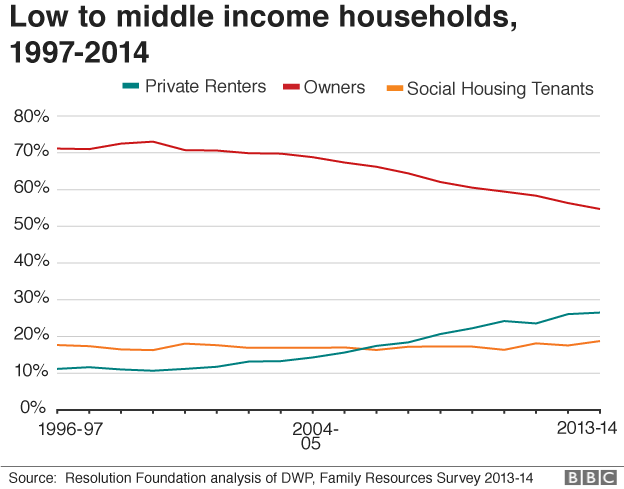

The plentiful supply of cheap labour arguably helped the UK economy to expand without facing the issue of spiralling wages - and this in turn held inflation and interest rates down, contributing to a decade-long boom in property prices, adding to the feelgood factor among middle income home owners, even if fewer people could afford to get on the property ladder in the first place.

But it also sowed the seeds of discontent in Labour's heartlands, as growing numbers felt left behind and marginalised by the pace of change in their communities, and a growing anti-EU feeling began to take hold.

And then there was Iraq.

In 2003, Blair had drawn on every last ounce of his persuasive skill to make the case for joining the US-led invasion to MPs and the wider public.

He had become convinced of the value of military action in pursuit of humanitarian aims and the need to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the US, in the wake of 11 September, 2001.

But the subsequent failure to find weapons of mass destruction appeared to confirm many people's worst suspicions about him - that he relied too much on spin and was not to be trusted.

It did not prevent him from winning a third term, in 2005, but he was forced to hand over to Gordon Brown earlier than he had wanted, in 2007. Like Mrs Thatcher in 1990, he had won three elections but ended up being forced out by his own side.

The legacy

The Blair family leave Downing Street in 2007

The years that followed were not kind, as the incoming Brown administration, and the Ed Miliband Labour team that followed seemed to do their best to talk down the Blair years - and then there was the Chilcot inquiry into the Iraq war, as well as the ongoing consequences of the invasion, for the region and global security as a whole.

Blair's supporters point to his domestic achievements - the minimum wage and all the new schools, hospitals and Sure Start children's centres that were built during his time in power - and they insist that his reputation will one day recover.

But with Britain on its way out of the European Union, and the Labour Party back in the hands of the left, it seems like much of what Blair stood for has been swept away.

His centrist brand of politics, characterised as the Third Way, a philosophy shared by his friend and political soulmate Bill Clinton, has fallen out of fashion in many Western countries and even Blair's style of politics, with its rigid emphasis on "message discipline", looks antiquated in the more freewheeling age of social media.

And despite winning three general elections, with big majorities, making him Labour's most electorally successful leader, his name has become a dirty word among many current active party members, guaranteed to generate boos and cat calls when it comes up at meetings.

It is very far from the future he must have imagined for himself on that cloudless spring morning in May 1997.

Yet Blair's supporters claim that his vision of a self-consciously modern, multicultural, socially liberal country, has endured - and that David Cameron's six years in government were shaped by it.

It is there in the Conservatives' commitments on foreign aid and promotion of gay rights, they say, as well as Britain's continued commitment to a health service free at the point of delivery, funded by taxation.

And, at 63, the man himself is still in the game.

He has ditched his business interests - that had generated so much negative publicity for him - to work full time on promoting moderate, centrist policy solutions, fighting battles that 20 years ago he must have hoped would have been won by now.