Reality Check: How many people are homeless in England?

- Published

The Liberal Democrats have pledged to end "the scandal" of rough sleeping, in their general election manifesto.

As of autumn 2016, there were an estimated 4,134 people a night sleeping rough on England's streets, more than double the number in 2010 and a 16% increase on the year before.

These are estimates based on local authorities either conducting a street count on a single night or making an estimation based on intelligence gathered from local services.

Labour has also pledged to end rough sleeping within its first term in government by making 4,000 additional homes available for people with a history of being on the streets.

The Conservatives pledge to halve rough sleeping over the course of the next parliament and eliminate it by 2027 by establishing a homelessness reduction taskforce.

The Green Party say they would give local authorities the same duties towards single people and childless couples as to families, while UKIP don't have a specific policy on homelessness, but say they will take measures to address homelessness among veterans.

Who is homeless?

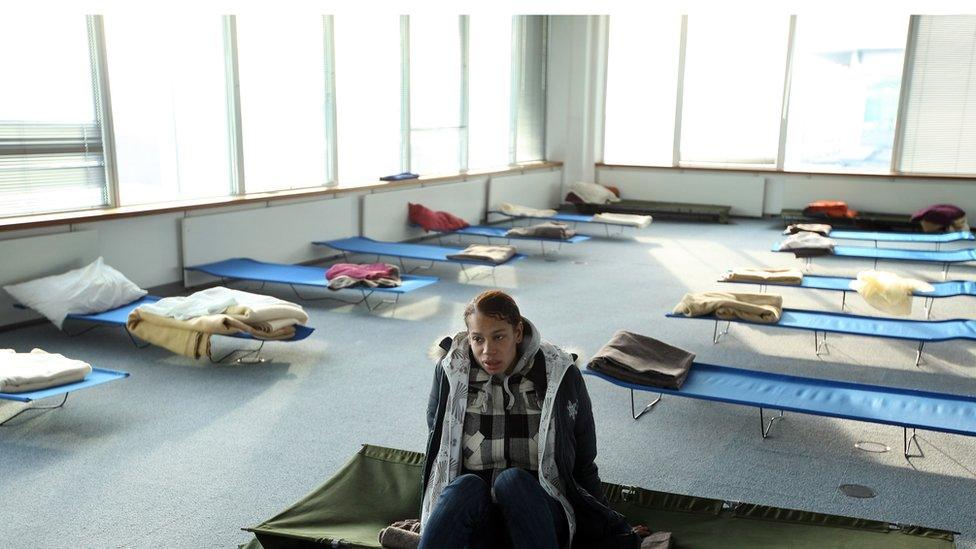

Although homelessness is often associated with images of people sleeping on the streets, in reality rough sleepers make up a small proportion of the total homeless population.

In 2016, local authorities in England accepted 59,260 households as being statutorily homeless and agreed to house them.

This means councils had decided those people or families did not have somewhere to live that they had a legal right to occupy, which is accessible and physically available to them and which it would be reasonable for them to continue to live in.

It's hard to say how much this figure overlaps with the number of rough sleepers recorded.

Priority need

But this still isn't the full picture - local authorities don't have a duty to provide housing for all homeless people, only those they categorise as being in priority need. Crucially, they must also consider that someone is "unintentionally homeless" before they will house them.

The 59,260 figure covers people who the council agrees are both "unintentionally homeless" and fall into a priority need category meaning the council has a duty to accommodate them.

Councils consider the following groups to be in priority need:

households with dependent children

pregnant women

people who are vulnerable in some other way, for example, because of mental illness or physical disability

In 2002 the vulnerable category was extended to include:

teenagers aged 16 or 17

those aged age up to 20 who have previously been in care

people who were vulnerable as a result of time spent in care, custody or the armed forces

people who have had to flee their home due to violence or the threat of violence.

Not vulnerable enough

There is a big group of people who don't have a place to live but who are not considered vulnerable enough in legal terms to qualify for housing.

Single adults with no children who don't have any of the specific additional vulnerabilities listed above will generally not be entitled to housing if they become homeless.

In 2016, 116,200 households in England applied to their councils for housing assistance because they said they were homeless.

Of those, there were almost 30,000 English households that councils agreed were homeless but said they did not have a duty to provide them with housing.

Numbers of households accepted as homeless and eligible for housing assistance had been falling sharply from the early 2000s until the end of 2009. Since then, they have been gradually rising.

The most common and fastest-growing reason for homelessness is the end of an assured short-hold tenancy, which allows landlords to evict tenants after an initial fixed term without a legal reason.

'Intentionally' homeless

Since 2009, when the lowest number of applications was recorded, there has been a 37% increase in people in England found by councils to be homeless and a 42% increase in people found to be in priority need and therefore owed accommodation.

Some of these people were rejected for housing because they didn't fall into a priority category. For some, however, they were rejected despite being considered to be in priority need because the council said they were intentionally homeless.

Shades of grey

The term "intentionally homeless" is a very contentious one. The legal definition is someone who is homeless when there is something they could have done, or not done, to prevent this from happening.

The most common examples are failure to pay rent without good reason (a good reason would be, for example, illness, redundancy, failure to manage personal finances due to mental ill health) or being evicted because of antisocial behaviour.

But there are plenty of shades of grey.

Recent cases where a council's decision to find some intentionally homeless was overturned in court included a pregnant woman who refused to stay in a hostel because of dirty conditions, and a woman who was considered to be intentionally homeless when she fled her matrimonial home after experiencing domestic abuse but not violence.

'Hidden homeless'

There is another group that does not appear in any official statistics - so-called "hidden homeless" people. The charity Crisis has estimated that in early 2015 there were 3.52 million homeless adults "concealed" within households in England. That is people who have no home of their own but may be sleeping on sofas, often resulting in overcrowding.

The current government is making attempts to tackle homelessness in the form of the Homelessness Reduction Act, which became law in April. This put a new duty on local authorities to give homeless people support to find somewhere to live and to help prevent any of their residents becoming homeless in the first place, even if they are not in priority need.

- Published13 April 2017

- Published5 April 2017

- Published23 December 2016