General election 2017: Deals, pacts and alliances

- Published

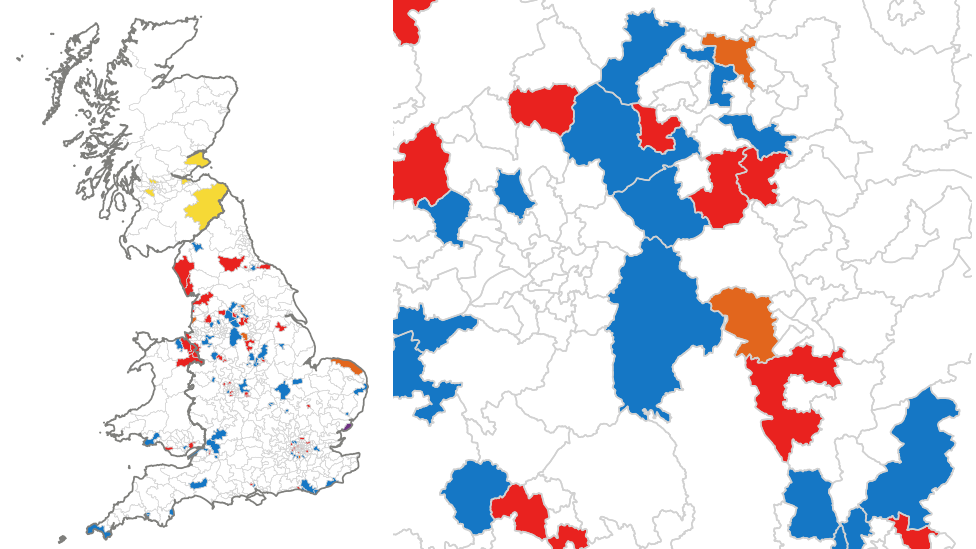

The 2017 general election looks set to see more co-operation between political parties than ever before.

The Liberal Democrats, Greens, UKIP, DUP and UUP have all said they'll stand aside in at least one constituency.

There won't be national deals though. Co-operation will be limited to local agreements. And it's difficult to be sure how big the impact will be.

Why are parties talking about deals?

Britain's first-past-the-post electoral system means that lots of MPs are elected on fewer than half of the votes cast in their constituencies.

At the last election, 333 out of 650 winning candidates received less than 50% of the vote.

Those MPs could have been defeated if all the people who voted against them had gone for the same alternative candidate.

Clearly, that would never happen everywhere. But parties who agree on some of the main issues potentially have a lot to gain if they can co-ordinate their supporters.

The Greens are keen to forge alliances

One option is to encourage tactical voting. A more direct approach is to enter some sort of alliance or pact which sees parties choosing not to put forward candidates in certain seats.

Even without an agreement, parties can try to affect the result simply by choosing not to contest some constituencies.

There's going to be more co-ordination of this kind in 2017 than we've seen at previous elections.

As a strategy, though, it does rely on voters being prepared to vote for a candidate from a party which would not have been their first choice.

It has happened before

One part of the country where electoral deals have been used before is Northern Ireland.

In 2015, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) agreed a pact not to stand against each other in four constituencies: Belfast North, Belfast East, Fermanagh & South Tyrone, and Newry & Armagh.

The deal was pretty successful. The unionist candidate won in three of the four seats. And the Sinn Fein majority was halved in Newry and Armagh.

This year, the UUP have said they won't put up candidates in Belfast North, Belfast West and Foyle. And the DUP won't stand in Fermanagh & South Tyrone once again.

The parties have held discussions about the possibility of extending the pact but without agreement so far.

There's also been talk of an "anti-Brexit alliance" which could include the main nationalist parties, Sinn Fein and the SDLP. But that plan now looks unlikely after the Green Party leader, Steven Agnew, said they wouldn't take part.

The impact of Brexit

In the rest of the UK, this kind of deal has been very rare in recent years but it looks as though there will be more co-operation between parties this time.

One reason is Brexit. It's a crucial issue for all of the parties and, significantly, an issue which cut across parties but cleanly divided voters into two camps.

Philip Hollobone has done a deal with UKIP

UKIP leader Paul Nuttall said he would put "country before party" by not standing candidates in some seats where there is a strongly pro-Brexit MP or where a pro-Brexit candidate has a chance of ousting a pro-Remain MP.

UKIP are standing aside in Christchurch and Bournemouth West. In Kettering, they've gone further by reaching a "memorandum of understanding" with Conservative MP Philip Hollobone. The deal includes plans for a regular forum where Mr Hollobone will meet UKIP members if he's re-elected.

On the other side of the debate, former Prime Minister Tony Blair has also said that he was prepared to "work with anyone" to stop candidates who back "Brexit at any cost" although he didn't suggest a formal electoral pact.

Progressive alliances

Brexit isn't the only issue. The Green Party is seeking support for what they call a "progressive alliance". Co-leaders Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley have written to Labour and the Liberal Democrats calling for a meeting "to discuss ways to beat the Tories at the general election and deliver a fairer voting system".

That's been rebuffed at a national level but in some places local parties have decided to co-operate.

Liberal Democrats in Brighton agreed to stand aside in the Greens' only seat - Brighton Pavilion. Former Lib Dem MP, Sir Vince Cable, who is seeking re-election, had tweeted his support for the idea.

The Greens have also unilaterally decided not to contest Labour-held Ealing Central and Acton and Brighton Kemptown, just as they did at the Richmond Park by-election in December where the Lib Dems overturned Zac Goldsmith's 23,000 majority.

Some Labour figures are calling on the party to respond in kind, stepping down Labour candidates in two seats - Brighton Pavilion and the Isle of Wight - where the Greens could win.

In an open letter from members including MPs Clive Lewis, Jon Cruddas and Tulip Siddiq, published in the Guardian, external, they said it was "important to maximise progressive votes" in order to avoid "the danger of a Tory landslide."

They've also suggested a deal which would see them stand aside in Plymouth Sutton and Devonport if Labour returned the favour in Totnes.

Will it work?

All of this negotiating will only be worth it if voters are prepared to back a party that isn't their first choice. There can be no guarantee that the Green voters will agree to switch en masse to the Labour candidate if the Greens stand aside.

The evidence from Northern Ireland is that pacts can work. But in that case they're based on a long-established division between unionist and nationalist voters. In the rest of the country it's harder to split the parties into two blocs so neatly.

However, voters do not identify as strongly with individual parties as they did in the past so there is probably more scope than previously for switching between parties.

And Brexit may well give voters a reason to vote for a candidate from a party that they wouldn't previously have considered.

- Published1 June 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published2 June 2017