General election 2017: Do strong leaders make good prime ministers?

- Published

Margaret Thatcher lost a number of senior colleagues who objected to her manner of governing

The soundbites are constantly repeated. "Strong leader". "Strong and stable leadership". "Strong and stable government". But what do they mean?

At first glance the terms are not contentious. It is easy to get agreement that "what we need is a strong leader", and few would argue that "what we need is a weak leader".

Yet, there is a lot to be said against an over-mighty leader.

If what we mean by a "strong leader", as we usually do, is one who maximises his or her power and takes most of the big decisions, that is far from the same as effective leadership.

More dispersed power among colleagues of high political standing will lead to better-informed decisions and guard against an individual leader listening only to people who are beholden to him or her and too ready to agree with the leader.

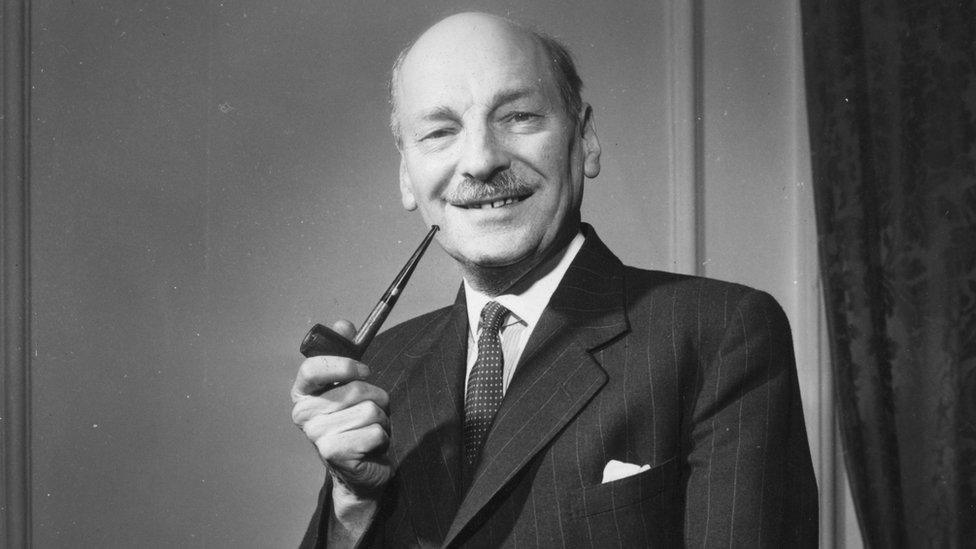

The immediate post-war Labour prime minister, Clement Attlee, is these days often seen as the instigator and driving force of a series of major policies that reshaped British society - such as the creation of the NHS.

But this was a government in which individual ministerial responsibility and collective cabinet responsibility were realities and Mr Attlee neither dominated the policy process nor tried to do so.

He believed in collective leadership - accepting that his colleagues "may perhaps be wiser than oneself".

His achievement was to keep together a team of people whose major figures differed sharply with each other.

In the classic definition of the term, Mr Attlee was not a strong leader, yet he headed a strong and stable government.

Clement Attlee had a quiet and unassuming personality that led many to underestimate him

The government over which Mr Attlee presided from 1945 to 1951, and that led by Margaret Thatcher from 1979 to 1990, were the two post-war administrations that made the biggest difference to this country.

In that sense, they were both strong governments.

Each of them essentially set the political agenda for a generation.

Many of the policies of the post-war Labour government remained in place until they were reversed by the Thatcher government, which was led in a completely different style from Mr Attlee's.

Mrs Thatcher was, indeed, a dominating prime minister and she succeeded in implementing controversial policies.

Stop and ponder

She lost, however, a series of senior colleagues who objected to her manner of governing, and it was that overweening style which led ultimately to her being ousted by members of her own cabinet and parliamentary party.

In contrast, Mr Attlee led the contentious Labour party for 20 years, retiring as leader at the age of 72.

Leaders who seek to gather more power in their office seldom stop to ponder that their successor, who may have a very different agenda, will inherit these same powers.

Thus, Ed Miliband, as Labour leader, persuaded the parliamentary Labour party to give up electing the shadow cabinet and accord him as leader of the opposition the power to appoint them.

In reality, voters can only give their backing to the leaders if they stand in their constituencies

As a backbencher, Jeremy Corbyn strongly opposed that change, but once he inherited those powers, he refused to return them to Labour MPs, even when they voted overwhelmingly last year to take them back.

Yet, keeping that extra power in the leader's hands illustrates the difference between a "strong leader" and a "strong leadership".

Although Mr Corbyn would then have less power individually, a leadership chosen by the parliamentary party would be stronger in its political composition and, arguably, in its appeal to the electorate.

Prime ministers, still more than leaders of the opposition, have shown a growing desire to set themselves apart from their senior colleagues.

They are encouraged to do so by their aides, for the more decisions are taken in the prime minister's office, the more influence and de facto power adheres to these closest advisers.

Theresa May took personalisation of power a rhetorical step further in the House of Commons this week when she repeatedly said that "a vote for me and the Conservative candidate" in the 8 June election will lead to strong and stable leadership and a better Brexit outcome.

The prime minister sticks relentlessly to her "strong and stable" slogan

The reality is that Mrs May's name will appear on the ballot paper only in her Maidenhead constituency.

Although some voters do vote for or against a party on the basis of what they think of the leader, a parliamentary election is not a presidential election.

It is still, above all, a choice, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, of one political party in preference to others.

The Conservative party won the 1970 general election at a time when Harold Wilson was significantly more popular than Edward Heath.

And even though Labour leader James Callaghan's personal popularity rating was 20 points ahead of Mrs Thatcher's on the eve of the 1979 poll, the Conservatives won that contest.

Leader reliance

At the time, Mr Callaghan was more popular than was his party, Margaret Thatcher less popular than hers. By 1983, after the Falklands War, Mrs Thatcher polled ahead of her party.

The choice of a government is much more than the choice of a prime minister.

The greatly respected political scientist and TV election analyst Anthony King, who died in January, observed last year that the best-governed countries "owe their good government in large part to the fact that their political institutions and political culture obviate the need for strong leaders".

He concluded: "A successful liberal democracy is liable to be one that is effectively "leader-proofed", one in which... it is made difficult for a strong leader to acquire and wield power and in which the government does not rely on strong leaders for its long-term success".

He was surely right.

Archie Brown is the author of The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political Leadership in the Modern Age

- Published27 April 2017

- Published2 June 2017