Reality Check: Is crime up or down under Tories?

- Published

![David Davis, speaking on the BBC's Question Time programme, said: "[Theresa May] was home secretary over six years in which crime came down by 30%"](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/1024/cpsprodpb/1034D/production/_95918366_davis2rc_election_quotepic.png)

In a spat on the BBC's Question Time programme on Thursday, Conservative minister David Davis and Labour's Rebecca Long-Bailey clashed on crime rates in England and Wales.

Mr Davis, the Brexit secretary, claimed that in the six years that Theresa May served as home secretary, from 2010 to 2016, crime came down by 30%.

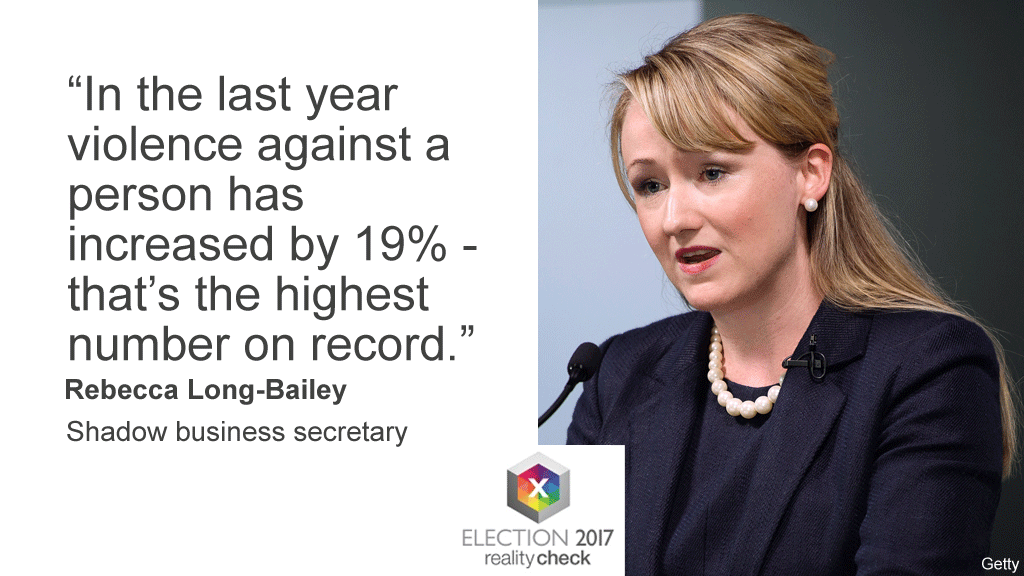

But Ms Long-Bailey, shadow business secretary, claimed that in the last year "violence against the person" offences had increased by 19%.

Both are talking about England and Wales only because Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate criminal justice systems.

Reality Check has been looking through the figures and what they mean.

So who is right?

The easy answer is that they are selecting figures from different ways of measuring different aspects of crime - neither is wrong but the more difficult question is which best represents how much crime people are actually experiencing.

Let's take each figure in turn.

Mr Davis is using figures from the Crime Survey for England and Wales. This is a face-to-face survey of 38,000 adults and children in which they are asked about their experiences of crime in the previous year.

Until 2016, the survey did not include fraud and cyber crime. If you exclude those crimes in order to compare like with like, then between 2010 and 2016, crime fell by 35%.

If you were to include those offences that were added in 2016, it would look like the crime rate has gone up.

The Crime Survey is generally considered a good measure of crime experienced by individuals because it is not affected by changes to how crime is recorded.

It also includes crimes that have historically been under-reported to the police - for example, domestic abuse.

This means the overall crime rate recorded by the survey is always higher than the number of crimes recorded by the police. Only an estimated 42% of all crimes recorded in the Crime Survey are reported to the police.

However, it has some limitations. It does not cover crimes against businesses or people living in communal residences like care homes, prisons or student accommodation. It is also excludes crimes where there is no victim to interview, for example homicides and drug offences.

And there is also a time-lag in the survey, so the figures are older than police figures. This means the survey is very good for looking at long-term trends but less good at spotting emerging ones.

Labour's claim

Ms Long-Bailey is using police recorded crime to arrive at a 19% increase in violent crime in a year. About half of those recorded offences did not result in injury.

Police recorded crime is a good measure of offences that are well-reported to the police but their accuracy has been called into question in recent years because of changes in methodology and they are no longer designated as national statistics.

The Office for National Statistics, external (ONS) says part of the rise is a genuine increase in crime in some areas, for example knife crime in London.

But some of it will be down to both changes in recording practices, and focused efforts from police to tackle certain crimes which leads to higher levels being recorded.

Two new harassment offences were added to the category "violence against the person". If you exclude these offences, the rise in total violent crimes is 14%.

There have been recent improvements in recording certain offences, such as modern slavery, which will push up the figures.

However, in the long term injuries from violence recorded by the NHS back up the idea that violence has generally been falling over time, not just under Mrs May's watch but since 1997.

What the crime figures say depends on which ones you choose to look at. Researchers at the ONS say on balance the evidence suggests there have been some genuine increases in certain types of crime over the last year but the long-term trend is that violence has been falling, not just under Mrs May's watch but for the last 20 years.

- Published2 May 2017

- Published27 April 2017