Who is Tim Farron? A profile of the ex-Liberal Democrat leader

- Published

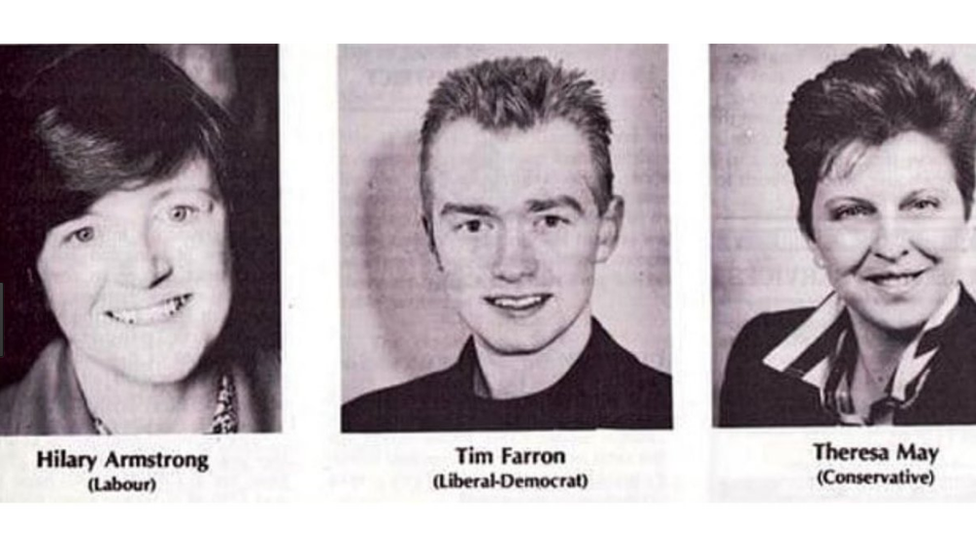

The 2017 general election was not the first time Tim Farron had taken on Theresa May.

Mr Farron was not long out of university when he was selected to fight the rock-solid Labour constituency of Durham North West at the 1992 general election, the kind of no-hope mission young politicians are expected to undertake to earn their spurs.

A 36-year-old Mrs May was also fighting her first Westminster election, with a similarly distant prospect of victory, although the two made very different impressions on the campaign trail.

"The person with the yellow rosette looked barely old enough to sup the pint we put in front of him," wrote the Northern Echo's correspondent, before adding that he was "quite a remarkable fellow".

"I've always been a bit of a front man," the 21-year-old Farron told another newspaper. "I like talking. I've got a big gob."

Mr Farron came third behind Labour's Hilary Armstrong and Mrs May.

It took him another three attempts to get elected to Parliament, overturning a Tory majority in Westmorland and Lonsdale, at the 2005 general election.

As one of eight MPs to survive the wipeout of Lib Dem MPs at the 2015 election, having turned his tiny majority of less than 3,000 in his Cumbrian seat into a healthy 8,949, he was in pole position to take over the leadership of the party he had joined at the age of 16.

His "big gob" had served him well.

His jokey conference speeches and matey persona made him a favourite among grassroots party activists, who saw him as one of their own.

He was arguably more in tune with their left-leaning views than his predecessor, Nick Clegg, and others who had taken ministerial jobs in David Cameron's coalition government.

Who is Tim Farron?

Date of birth: 27 May 1970 (age 46)

Job: Lib Dem leader, MP for Westmorland and Lonsdale since 2005

Education: State-educated at Lostock Hall High School and Runshaw College, Leyland, in Lancashire, and Newcastle University

Family: Married wife, Rosie, in 2000, two daughters and two sons

Hobbies: Blackburn Rovers fan and music lover. In 2008, he named his three heroes as Clash singer Joe Strummer, former Liberal leader Jo Grimond and Chronicles of Narnia author and theologian CS Lewis

He liked to joke he had not "made the cut" when Mr Clegg had been dishing out ministerial jobs in 2010.

Instead, he became party president, positioning himself as a "critical friend" of the coalition and building up his power base with activists.

Although he endorsed the Cameron government's austerity measures, including controversial spending cuts and benefit restrictions, he frequently took aim at his party's coalition partners, describing them at one point as "toxic".

Crucially, he voted against plans to raise the cap on university tuition fees to £9,000, in January 2011, a U-turn which became a defining moment for the Lib Dems, from which they have still not fully recovered.

In the leadership contest against former Health Minister Norman Lamb that followed the 2015 election, he could present himself as a "clean skin", untainted by the coalition years that had brought the party to its knees.

He won with 56% of the vote, but the scale of the task facing the 46-year-old father-of-four was daunting.

Mr Farron throws himself into campaigning with a search and rescue team...

and a novelty "colour dash" fun run...

...and a canine fan

In one of the biggest reversals in British political history, the Lib Dems had gone from sitting around the cabinet table to fighting for airtime and attention with fringe parties in the space of a few weeks.

When Nick Clegg led the Lib Dems in opposition he was guaranteed two questions every week at Prime Minister's Questions.

As the leader of the fourth largest party in the Commons, Mr Farron was limited to one question every four weeks, which was often drowned out by jeers from MPs.

Last June's EU referendum appeared to the throw the party a lifeline.

The Lib Dems had always been the most pro-European of Britain's political parties, and after the historic vote to take Britain out of the EU, Mr Farron sought to position his party as the voice of the 48% who had voted against Brexit.

He vowed to use all of the party's voting strength in the House of Lords, where it has more than 100 peers, to try to thwart what he claimed was Theresa May's vision of a "hard Brexit".

In December, the party pulled off the kind of by-election victory it used to specialise in, when its candidate, Sarah Olney, defeated former Tory MP Zac Goldsmith in Richmond Park, south London.

Leaders' profiles

Mr Goldsmith, a leading Brexiteer, had called the election in protest at his party's backing for a third Heathrow runway, only to find his 23,000 majority overturned by Ms Olney, who won by 1,800 votes.

When Theresa May called a snap general election for 8 June, Mr Farron came out clearly in favour of a second referendum on the terms of any Brexit deal, in which his party would campaign for Britain to remain in the EU.

"This is an opportunity to stop May in her tracks in her zealous pursuit of a disastrous hard Brexit, to keep Britain in the single market, to have a decent opposition to stand up to a Conservative government moving from crisis to crisis," he wrote in The Guardian, external.

Despite their tiny number of MPs, he claimed the Lib Dems could replace Labour as the "real opposition" to the Conservatives.

The party was in second place to the Conservatives in a lot of constituencies, he argued, and had seen its membership soar to its highest level this century.

The Lib Dems got a dose of reality at the local elections a few weeks later, when despite increasing their vote share by 7%, they lost 40 seats.

Mr Farron now said the party's aim was to double its number of MPs - and mitigate what he said would be a Tory landslide.

But while the party increased its tally of seats from nine to 12, its vote share fell from 7.9% to 7.4%.

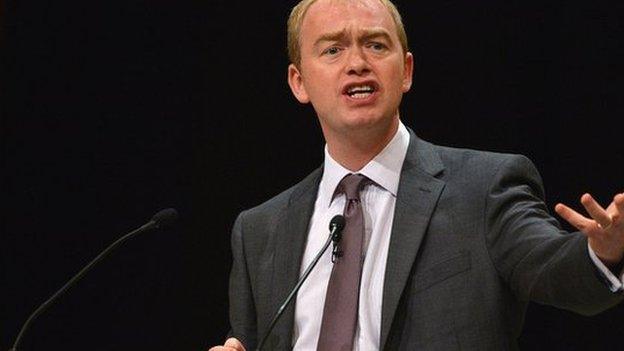

Tim Farron made a name for himself among activists with his party conference speeches

During the campaign, Mr Farron found himself pushed off course by questions about his attitude to gay sex.

The Lib Dem leader, who was baptised at 21 and rededicated himself to God at 30, has always been open about his Christian faith, although he accepts that some in his party see it as a weakness.

During the two-month party leadership campaign, he told the Guardian, external that he had sought advice from God before deciding whether to put his name forward.

He had taken flak for abstaining in a Commons vote on same-sex marriage, although he supported the landmark bill legalising gay marriage at all its crucial stages.

But after a fresh round of media questions about where he stood, he decided to try to kill it off as an issue, in an interview with the BBC.

He said he did not "want to get into a series of questions unpicking the theology of the Bible" but did not want people getting the "wrong impression" about his views either.

"I don't believe that gay sex is a sin," he said.

'A day off school'

Mr Farron - who was born and educated in Lancashire - joined the Liberal Party at the age of 16, after first becoming a member of Greenpeace.

He was also a member of political reform campaign Charter 88, homeless pressure group Shelter and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

He once revealed his true political awakening had come at the age of nine, when he had been allowed to stay up until the early hours to watch the 1979 general election, and had "got a day off school".

He was active in student politics at Newcastle University, becoming the first Lib Dem to be president of the university's student union.

His skirmishes with the Socialist Workers' Party made the national news in 1991, when the National Union of Students rejected a call for a national campaign of sit-ins to protest against rising debt.

According to the Independent, NUS executive member Tim Farron rounded on left-wing student groups, calling them ''hangers on'' who were using the occupations to recruit members and "sell newspapers".

A year earlier, he took a swipe at the Labour Party from the platform at the Lib Dem conference, describing it as "about as radical as an episode of Terry and June''.

A lifelong Blackburn Rovers supporter, Mr Farron used what little spare time he had at university to play football.

He also played keyboards in a band, which were called The Voyeurs, until they worked out what that meant, and then Fred the Girl. Mr Farron told Total Politics magazine they were once offered a recording session with Island Records.

In 2005, the Lib Dem leader was rendered "speechless" when he was introduced to his "teenage pin-up" Wendy Smith, of 1980s band Prefab Sprout

After graduating with a politics degree in 1992 - the year in which he first stood for Parliament - he worked in higher education for Lancaster University and St Martin's College in Ambleside for over a decade before becoming an MP.

Mr Farron is steeped in the Lib Dem tradition of pavement politics - learnt from years serving on Lancashire County Council, South Ribble Borough Council and South Lakeland District Council - and he made a point of getting out and meeting the voters at the general election, even if it meant the occasional clash with an angry Brexit supporter.

Pitching himself as the anti-Brexit leader gave him a unique selling point, but also opened him up to the charge that he is anti-democratic and suffering from sour grapes.

- Published14 May 2015

- Published23 June 2015