Making sense of the Labour and Lib Dem manifestos

- Published

Tim Farron, Liberal Democrat leader, campaigning in south London

The Liberal Democrats and the Labour parties have both set out their manifestos. It has been widely noted that there is a big gap between them when it comes to Brexit - but the two parties also disagree on tax and spending policy in quite a surprising way.

The first thing to understand is the difference between current spending and capital spending.

Broadly speaking, current spending is day-to-day running costs of the state - benefits, wages and so on.

Capital spending is spending on stuff - buildings, kit and infrastructure. In 2015-16, we spent £682bn on current spending and £72bn on capital. We spend a lot more on current than capital.

A prevalent norm in British politics is the idea that, over the medium term, we should "only borrow to invest". That is to say that - setting aside years when economic weakness is a problem - the tax take should usually cover day-to-day running costs. (We should, in the jargon, "run a surplus on the current budget".)

The idea is to only borrow to cover investment in new infrastructure or equipment. Versions of this rule are present in both the Labour and the Liberal Democrat manifestos.

It is, in principle, possible to meet this rule while spending backbreaking amounts on capital. So the two parties have also set out rules on the total debt stock. The intuition here is that they will not borrow without limit.

The Lib Dems' rule is a tighter constraint. Note, though: in both cases, the parties also have an emergency knock-out clause. In the event of recession that requires a policy response, the rules will be suspended. What does it all mean for the two parties' plans?

Lib Dem tax and spend

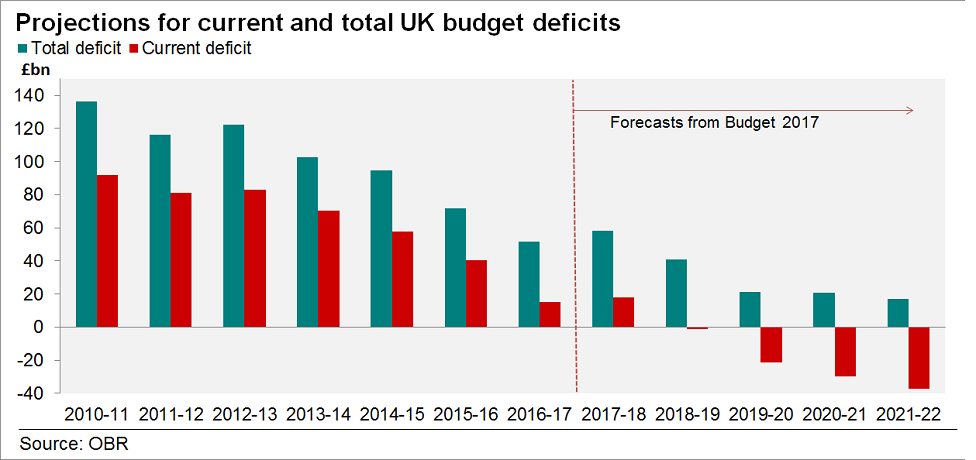

First of all, here is a chart showing the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates for the total deficit (in green) and the current budget (red) on the Tories' plans, as presented at the Budget. They imply borrowing £52bn this year, of which £15bn will be the current budget. You can see that the Conservatives' plans imply a shrinking overall deficit and current deficit.

The Tory plans, indeed, would mean balancing the current budget in 2018. That is when the red deficit line goes negative.

This would mean a current surplus a year early for the Lib Dems and three years early for Labour. The plans would also mean ending up with a £37bn current surplus in 2021-22. Neither party has committed to running a current surplus of that size, so it gives them some "headroom". Both opposition parties had the option of increasing spending without raising tax.

The Lib Dems' attitude to this is straightforward: they intend to use some of this slack. They say: "Our plans mean borrowing £5bn more than government plans in 2018-19 and £14bn more 2019-20 for day-to-day spending."

Labour, though, is more complicated.

John McDonnell, Labour's shadow chancellor, campaigning in the rain

Labour's tight grip

Labour could spend £37bn a year more on current spending than the Conservatives' plans in 2021-22 - the year when their target is fixed - without raising a penny more in tax while staying within their fiscal rules. In short, they could spend the Tories' surplus - but say they will not.

That is not to say Labour will not increase spending. On the contrary, Labour has identified £48.6bn of current extra spending in that year. But they are funding it through £48.6bn of tax rises. They have made an additional short-term unmatched spending commitment on local government - £1.5bn of grants to local authorities. But that's all the slack they have used.

It is a little surprising, given their rhetoric, that they want to maintain much of the benefits freeze while intending to run a £37bn current budget surplus. Labour, as the IFS has pointed out, is currently taking a harder line on the benefits bill than the Lib Dems.

Capital questions

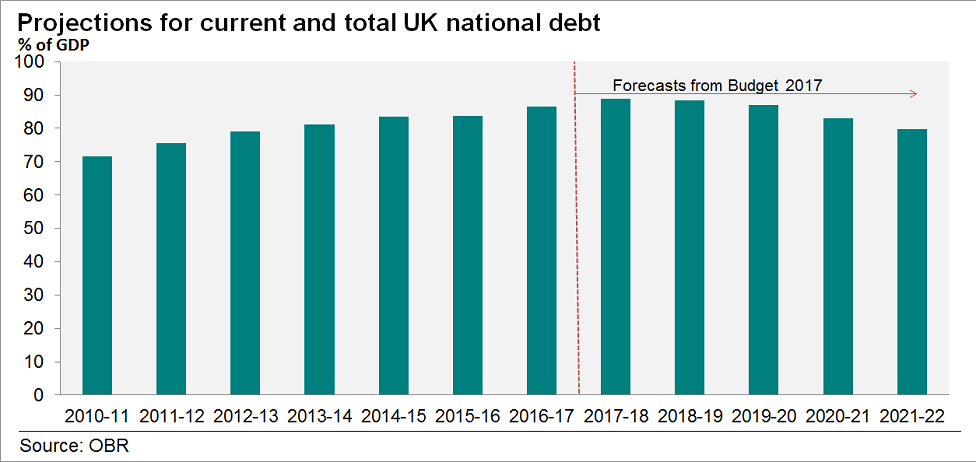

This tight position on the current budget creates space for capital spending. While the capital budget is separate to the current budget, Labour wants total debt as a share of GDP to be lower at the end of the Parliament than this year. That means debt should be no higher than about 89% of GDP in 2021-22.

Labour's very tight current budget position would give them room to spend more on capital. If you assume the OBR's growth projections will hold and they run that big current surplus, Labour could increase total borrowing by a total over the five years of £175bn without breaching their fiscal rules. That is much, much more than they could plausibly need: Labour has talked about spending £25bn a year on capital, via their infrastructure fund.

The Lib Dems' capital plans are more modest: they want to raise capital spending by £5bn a year in 2019-20, with a view to finding more projects to invest in - a stream of spending that, over the medium term, should reach £100bn. They are concerned about how hard it is to identify and fund capital projects quickly.

On domestic policy, the Lib Dems are seeking a more modest reshaping of Britain. In lots of ways, you can see Labour's plan as being much grander. It is about making us a bit more Germanic. It is about creating a sustainably larger state.

But the package leaves us in an unexpected place: Labour has a looser fiscal rule than the Lib Dems on the current budget, but plans to run a tighter current balance than them. Labour is proposing to spend much more than the Lib Dems on the current budget, while being less generous on welfare.

Labour's platform, being more radical, is more open to complicated and unhelpful questions. They have also left themselves an enormous buffer that they can spend if, say, their proposed tax rises do not raise as much as is hoped. But in their determination to look credible, it's slightly puzzling just how much fiscal room they have decided to leave themselves.