What chance for a new 'centre ground' party in the UK?

- Published

Emannuel Macron: Can anyone in the UK emulate his success?

New political parties have a remarkably high failure rate in the UK. They almost never succeed - but are things different now?

The success of new French President Emmanuel Macron, who created a liberal pro-European party of government, En Marche, from scratch in less than two years, has made some people wonder if it could happen in the UK.

Conventional wisdom says a fresh face could never rise so rapidly to the top - the first-past-the-post electoral system is biased in favour of the existing "big two" parties, the argument goes.

But politics is more fast-moving and fluid than it has ever been and there appears, to some at least, to be a gap in the market.

"The Tories are committing Euro-suicide. Labour is kidding itself that a party with no economic policy can govern. There is a chasm in the middle of British politics," wrote Tony Blair's former speech writer Philip Collins recently in the Times.

En Marche of the Day: Gary Lineker is looking for a political home

Dominic Cummings, who masterminded the Vote Leave campaign, said on Twitter this week that a new party looks increasingly "tempting" (although he does not spell out what it might stand for).

Even Gary Lineker has got in on the act.

"Anyone else feel politically homeless? Everything seems far right or way left. Something sensibly centrist might appeal?" Lineker asked Twitter recently.

Within minutes, one of the Match-of-the-Day-presenter's followers had called for the creation of En Marche of the Day, with the ex-England footballer as leader, naturally.

Anti-Brexit Conservative MP Anna Soubry sounded like she could hardly wait for the birth of a new party in a New Statesman interview, external.

"If it could somehow be the voice of a moderate, sensible, forward-thinking, visionary middle way, with open minds - actually things which I've believed in all my life - better get on with it."

But she was speaking before the general election.

Labour is back in business

The Corbyn surge has silenced talk of a Labour breakaway for now

Jeremy Corbyn's better-than-expected performance at the general election has killed off any talk of new parties in the Labour ranks, for now.

"Moderate" Labour MPs who thought Mr Corbyn was leading their party to oblivion have been forced to eat their words and rally behind him, as he agitates for another general election.

But the truce may be temporary, says Prof Tim Bale, of London's Queen Mary university, with continued "scepticism" among Labour MPs about "whether the direction Jeremy Corbyn is taking the Labour Party can actually get it into government in the long term".

"I don't think the split between the Parliamentary Labour Party and Jeremy Corbyn has gone away. It's probably gone underground for a little bit but it hasn't disappeared," he adds.

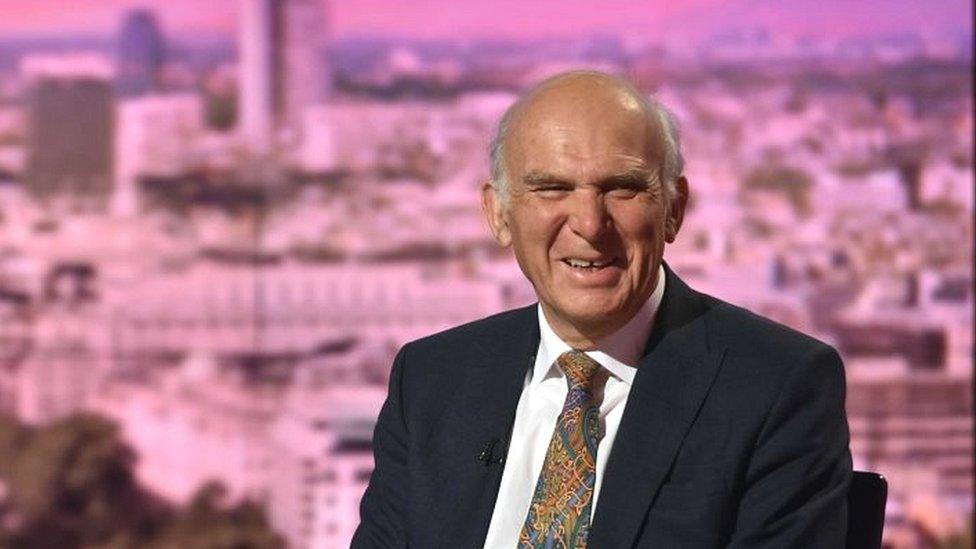

We already have a centre ground party

Sir Vince Cable offers a friendly welcome to Labour "refugees"

"Why don't you join the Liberals?" is the taunt currently being directed at "moderate" Labour MPs by the more hard core Corbynistas.

Lib Dem leader elect Sir Vince Cable has said he would happily provide shelter for "refugees" from Labour but he is directing his energy towards "cross-party" working to scupper what he regards as Theresa May's "hard" Brexit.

With just 12 MPs, he knows that this is his party's best hope of wielding any real influence, for now.

The rise of the 'definitely-not-a-new-party'

Tony Blair: It's a "new policy platform", not a party, OK?

If launching a new party is too hard, why not launch something that looks a bit like a new party but isn't? Something that could, perhaps, be quickly turned into one if the time was right.

Earlier this year, Tony Blair launched a "new policy platform to refill the wide open space in the middle of politics". The former Labour prime minister insisted his Institute for Global Change was more than a think tank, saying it will arm politicians with policies to "rebuild" the centre ground and combat the growth of right wing populism.

Former Lib Dem leader, Lord Ashdown, has, meanwhile, helped to set up More United, an organisation inspired by the words of murdered Labour MP Jo Cox, who famously appealed for tolerance in her maiden Commons speech.

More United pumped some fairly serious cash into the campaigns of mainly Labour and Lib Dem MPs - the sole Tory was Anna Soubry - at this year's general election.

The money was raised through crowdfunding and the MPs who got elected, and who had signed up to More United's policy agenda - tolerance, "working with the EU" and fighting inequality - are proudly displayed on the group's website, external, sans party branding.

Bye, then

Robert Kilroy-Silk: He ran out of parties to join

Recent British politics is littered with the remains of dead parties. Here are just a few of them:

Libertas - Ambitious attempt to set up a pan-European party by Irish telecom magnate Declan Ganley. Won one European Parliament seat in France.

Veritas - Where Robert Kilroy-Silk went when he stormed out of UKIP. Merged with another Eurosceptic fringe outfit, the English Democrats, after Kilroy-Silk's departure.

NO2EU - Late rail union leader Bob Crow's bid to make the left-wing case for leaving the EU. Morphed into a trade-unions-against-the-EU campaign.

The Jury Team - Late millionaire Tory donor Sir Paul Judge poured money into independent candidates. Few were elected.

Your Party - An early stab at crowd sourcing policies by a group of marketing executives. Met with apathy and quietly killed off.

It can be done

Nigel Farage: Owes it all to the European Parliament?

It is not all doom - small parties can and do break through on to the national stage in the UK. The public are willing to give them a hearing in a way that they never did in the past - witness the seven-way debates at election time and the extraordinary rise of the SNP.

But the ones that succeed tend to be born in the angry margins, speaking up for voters who feel their views are being ignored by the mainstream. The "centre ground" tends to be the preserve of political insiders, who can come with a lot of unhelpful baggage.

UKIP and the Green Party both built successful grass-roots movements from the ground up, gaining their first foothold in the European Parliament, which uses a form of proportional representation and is therefore kinder to smaller parties.

Neither has been able to get more than one MP elected at Westminster, however. To do that, you probably still need to attract significant numbers of MPs from other parties, to make you look like a serious contender for power.

Like the SDP did.

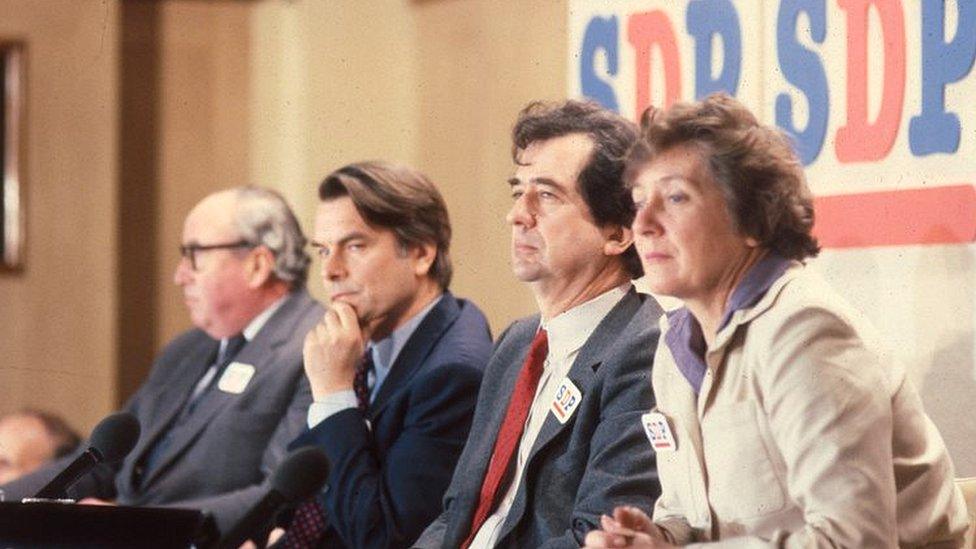

Three letters that spell disaster?

The Gang of Four: Cheer up, it might never happen

They were going to "break the mould of British politics" and for a brief period it looked like they might just do it.

The Social Democratic Party (SDP) was formed in the early 1980s by a group of high-profile Labour MPs disillusioned with the "hard left" direction their party was taking.

The new "centre ground" force soared in the opinion polls and eventually recruited 28 Labour MPs, and one Tory, to its ranks.

Their efforts to gain power through an alliance with the Liberal Party succeeded in getting a quarter of votes at the 1983 election, but, thanks to first-past-the-post voting, that only translated into 23 MPs. They had a similar result in 1987 prompting moves which ended up with a merger with the older party - to form what would become the Liberal Democrats.

The Lib Dems went on to get more than 50 MPs at later elections but the party has so far failed to match their 1980s vote share.

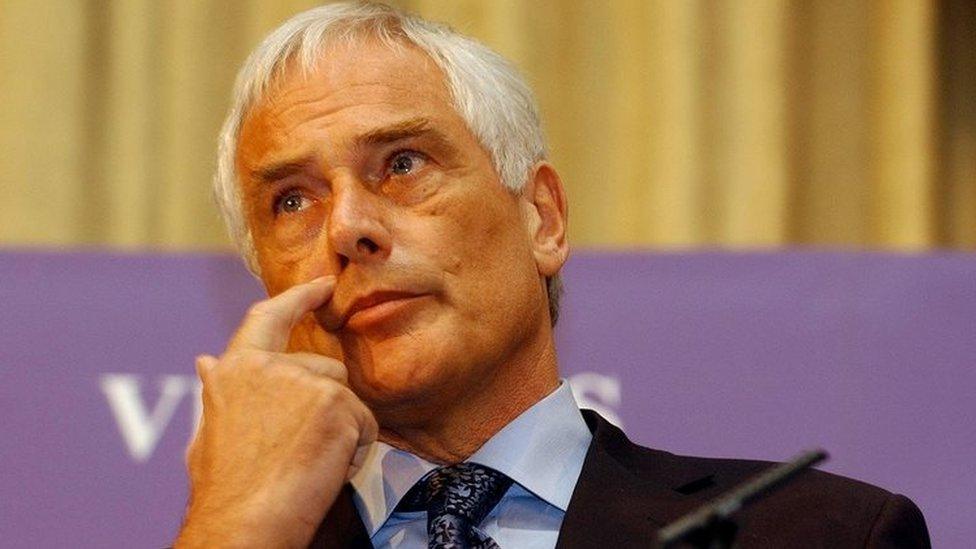

Waiting for the great leap forward

SDP leader Steve Winstone: Yes, it is still a thing

The SDP never quite died. David Owen's party lives on, minus David Owen or any of the original "gang of four" founders, its flickering flame kept alive by a handful of diehards who never accepted the merger with the Liberals and new members attracted by what they see as its "sensible", centrist message.

"Just because we failed once, it doesn't mean we are going to fail again," says SDP leader Steve Winstone, a former UKIP election candidate.

Today's SDP, which got fewer than 500 votes at the general election, is all about "direct democracy", electoral reform and regional government. It is based in Sheffield and claims to be growing quickly.

The Liberal Party also survived the 1988 merger. Its leader, Steve Radford, got 2,000 more votes than the Liberal Democrat candidate at this year's general election in the Liverpool, West Derby constituency, although still finished third.

He looks forward to the creation of a new centre ground party at Westminster because it would "take a great weight off our shoulders", ending the public's confusion between the Liberal Democrat "defectors" and his own party, which he says is the true home of "liberalism".

"They (the Lib Dems) have damaged our brand," he tells BBC News.

The SDP and the Liberal Party are both in favour of Brexit because, they say, the people voted for it. Neither leader would discuss the size of their parties' membership, but it is not a large number. Oh, and - 80s nostalgists take note - Steve Winstone has not ruled out an alliance with the Liberals to fight for electoral reform...

'We live in interesting times'

Is there anybody out there who could lead a new party?

So, if building a movement from the grass roots is a non-starter, if you have ambitions of running the country, but launching a new party with the same old, tarnished Westminster faces is likely to turn voters off, then what exactly would it take?

"You would need at least 100 or so MPs," and it would need to be a "spectacular" and game-changing coup, says Prof Tim Bale.

"It would need to be exciting enough - and big enough and sexy enough - to convince people."

A charismatic leader, without too much baggage (sorry, Tony) is a must.

And timing would be everything. If the launch is too far from the next general election, the shine could come off and the whole enterprise come crashing to the ground before anyone gets a chance to vote for it, says Prof Bale.

The disappointing performance of the Lib Dems at the general election suggests a new party would need to have a broader policy agenda than just being against Brexit, he adds.

"It still seems to me to be unlikely. But we do live in interesting times so I wouldn't rule anything out."