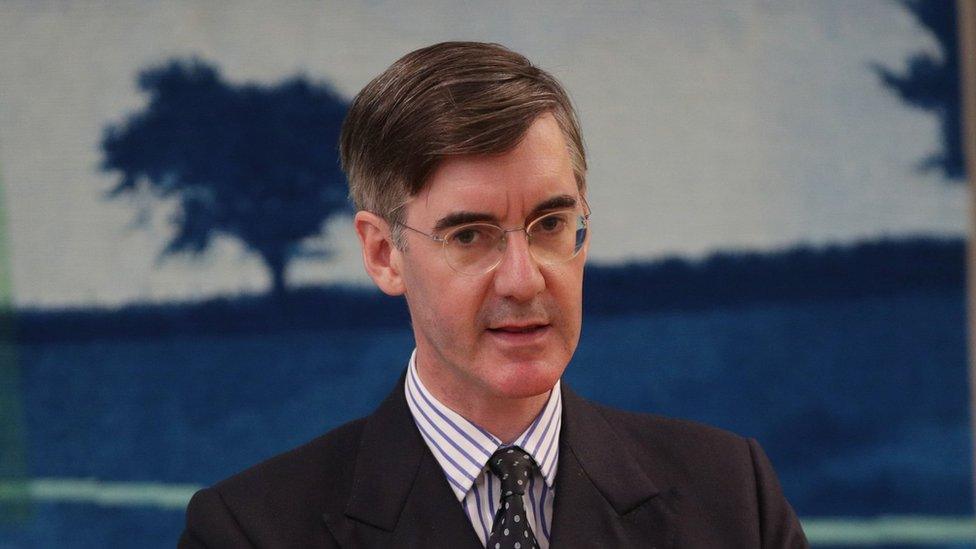

Rees-Mogg ignites fresh row over abortion

- Published

Rees-Mogg on abortion and gay marriage

Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg is the first British politician in decades to publicly oppose abortion in all cases, even when a woman has been raped.

It was not, he stressed, government policy, but his own personal view based on Catholic teachings.

He got credit from his supporters for his candour - not for Mr Rees-Mogg the evasions and caveats of other politicians who have found their personal religious convictions out of step with party policy and the prevailing orthodoxy.

But others found his views "extreme" and wildly at odds with majority opinion in the UK.

Tory MP Margot James called them "utterly abhorrent".

It would certainly be a strange way to launch a party-leadership bid, although Mr Rees-Mogg insists he has no ambitions in that direction, whatever social media says about "Moggmentum".

Former Tory leader Iain Duncan Smith said Mr Rees-Mogg's appearance on ITV's Good Morning Britain programme could well be a "tipping point" if the North-East Somerset MP ever changed his mind about that.

Former Conservative MP Ann Widdecombe, a Catholic who has previously spoken out against abortion, told BBC Radio 5 live's Emma Barnett Mr Rees-Mogg's views were "nothing like as rare as you may think" and they would have no long-term effect on his career.

"Now, can a politician say what he thinks?" she said. "Or are we simply going to end up in a situation where every time you say what you think, you end up with an adverse effect, so in the end you simply dodge it?"

So why is abortion such an apparently taboo subject in British politics?

Settled matter?

In the US, being against abortion is a standard position for Republican politicians and a reliable dividing line with the Democrats, although the issue of exemptions for rape and incest is a highly sensitive one.

It still causes controversy when someone running for office voices their opposition to such exemptions, as Republican hopeful Marco Rubio did last year.

But American politicians are expected to be upfront about their religious beliefs and take a position on moral issues that in the UK tend to be seen as personal matters.

Piers Morgan, who prodded Mr Rees-Mogg into revealing his views on the Good Morning Britain sofa, tried a similar line of questioning, on his CNN show in 2012, during the Republican primaries.

The former Mirror editor asked White House hopeful Rick Santorum, a devout Catholic, if he would let his daughter get an abortion after rape.

Mr Santorum said did not say yes outright, adding that he would explain to her that a baby, even when "horribly created", was still a "gift, in a very broken way".

Donald Trump, who before running for president was pro-choice and is now firmly against abortion, draws the line at cases of rape, incest, and when the mother's health is endangered.

The issue of abortion in Britain is seen by many people as a settled matter - it rarely comes up at general elections.

"We are a pro-choice country, we have a pro-choice Parliament," said Katherine O'Brien, of the British Pregnancy Advisory Service.

"Every politician is entitled to hold their own opinion on abortion. But what matters is whether they would let their own personal convictions stand in the way of women's ability to act on their own."

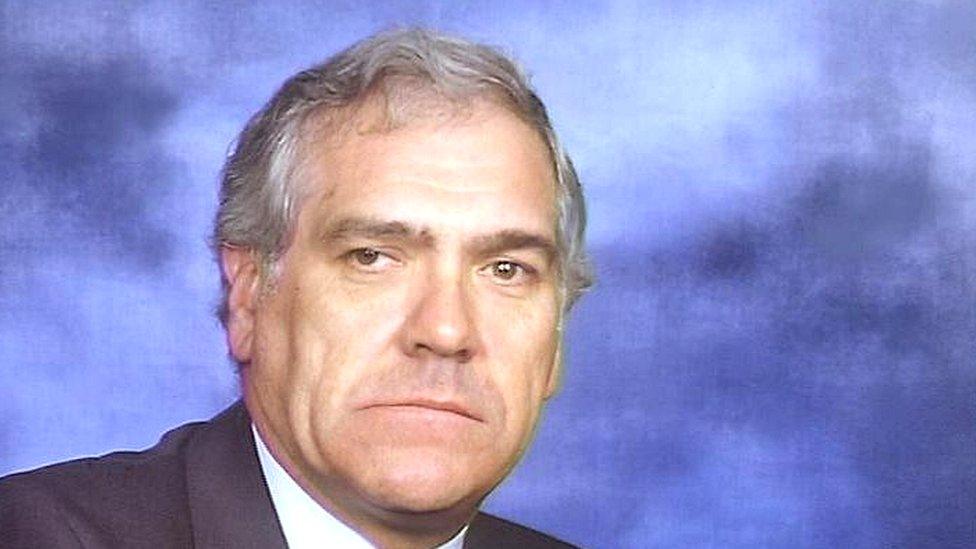

Ann Widdecombe is a longstanding opponent of abortion

In fact, there have been several serious attempts to restrict abortions since Liberal leader David Steel succeeded in liberalising the law in 1967, resulting in some impassioned debates in the House of Commons.

In 2008, MPs voted on cutting the 24-week limit, for the first time since 1990, in a series of amendments to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill.

There were calls for a reduction to 12, 16, 20 or 22 weeks, but MPs rejected the proposals in a series of votes.

Going further back, Liberal MP David Alton resigned as his party's chief whip in 1987 to launch what turned out to be an unsuccessful bid to ban late abortions.

The first version of Mr Alton's bill did not include an exemption for women who had been raped - he argued that they represented a tiny minority of cases.

The exemption was added at a later date, but supporters of the bill made it clear that they viewed it as a stepping stone to a complete ban.

Conservative MP Terry Dicks told MPs: "I understand and am concerned about incest and rape and the implication of a child being born as a result. I do not know the answer, but I do know that life is important from the minute that conception takes place.

"Of course ladies have rights and we must consider them, but they also have obligations and responsibilities that they have to face up to."

Theresa May and Arlene Foster hold differing views on abortion

Few MPs have been as outspoken in their opposition to abortion since, although senior figures in all parties have expressed their personal support for reducing the time limit.

And there have been cases where politicians have had to wrestle with their conscience on the issue.

Labour's Ruth Kelly, a member of Catholic organisation Opus Dei, refused to take a ministerial role at the Department of Health to avoid conflicts with her beliefs.

The issue has crept back on to the political agenda in recent months with the deal between Theresa May and the DUP to keep the Conservatives in power.

Unlike in the rest of the UK, abortion is illegal in Northern Ireland unless a woman's life is in danger or there is a serious risk to her mental or physical health.

And the DUP has consistently opposed abortion, with its leader, Arlene Foster, saying: "I would not want abortion to be as freely available here as it is in England."

Tory MP Terry Dicks backed a ban on abortions in the 1980s

But, in an unexpected turn of events, Northern Irish women have now been granted access to terminations on the NHS in mainland Britain.

In June, the government had to draw up emergency plans to head off a revolt by Conservative MPs who joined forces with Labour in opposing the DUP's stance, to the evident delight of some Tory ministers.

As the law was changed, Education Secretary and Equalities Minister Justine Greening said: "Let us send a message to women everywhere that in this Parliament their voices will be heard and their rights upheld."

Prime Minister Theresa May is also opposed to changing the abortion laws and was careful to distance herself from Jacob Rees-Mogg's opinions, while stressing that it was a "long-standing principle" that abortion was a "matter of conscience" for individual MPs to decide on.

Mr Rees-Mogg knows his views are not mainstream in Conservative circles at Westminster. In his Good Morning Britain interview, he said women's abortion rights under UK law were "not going to change".

But he argued that his party was more tolerant of religious views than the Liberal Democrats, whose former leader Tim Farron quit after facing repeated questions about his views on gay sex.

"It's all very well to say we live in a multicultural country... until you're a Christian, until you hold the traditional views of the Catholic Church, and that seems to me fundamentally wrong," he said.

"People are entitled to hold these views."

- Published6 September 2017